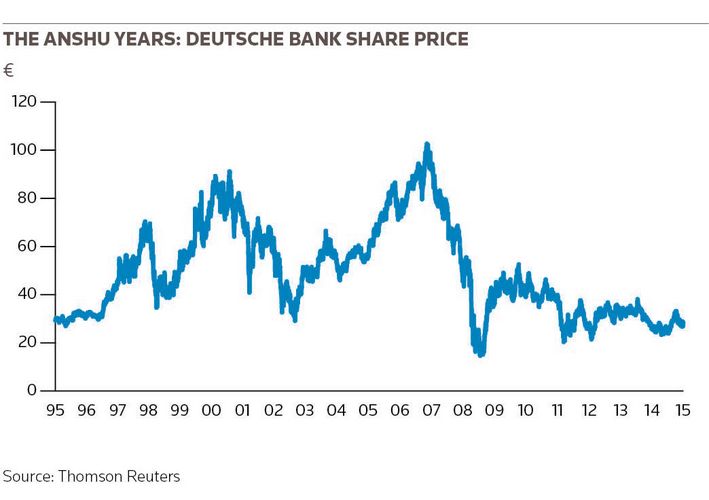

Last Tuesday was Anshu Jain’s last day as co-CEO of Deutsche Bank. It was almost 20 years to the day since the then 32-year-old banker left his managing director role at Wall Street behemoth Merrill Lynch to join the German bank, widely regarded back then as a sleepy European lender focused primarily on the German Mittelstand.

Jain was taking a gamble. His former boss Edson Mitchell had called him months earlier and persuaded the young Indian to jump ship, as Mitchell himself had done shortly before. His pitch: to help build the pre-eminent European investment bank.

The two firms were like night and day. Deutsche languished well behind the big US houses. In fixed income, it barely scraped into the top 20. Even in bread-and-butter corporate transactions, it was seen as a bit-part player: two months earlier, the German government had embarrassingly chosen Goldman Sachs to lead the Deutsche Telekom IPO because German firms lacked the clout to sell the deal internationally.

“Deutsche was a Triple A rated German commercial bank, which had a strong balance sheet but frankly very little global capability,” said one senior banker who was there at the time. “No European firm had truly globalised at that point but we thought that Deutsche had the best chance of getting there.”

Deutsche’s board had made its first steps towards the big time back in 1990, when it bought British merchant bank Morgan Grenfell. But that wasn’t enough. Mitchell had been brought in from Merrill to turbo-charge the build-out. Jain was one of his first hires.

The two evidently had a strong relationship. Pleased with the progress Jain was making – first servicing hedge fund clients, then with setting up a new unit bringing together the sales teams, Mitchell rewarded his protege with a series of promotions. By 2000, the 37-year old Jain managed three-quarters of the markets business.

Exponential growth

Helped by the opportunistic purchase of Bankers Trust in 1999 (BT had been hobbled by major losses the year before, but brought considerable – if controversial – derivatives expertise), Deutsche grew the markets business exponentially. Derivatives were a major part of that growth: this was a period of huge product innovation.

The derivatives revolution was started by JP Morgan, with Bill Winters leading the charge, but Deutsche soon matched the giant American bank stride for stride. Jain was the driving force. The bank’s credit derivatives trading volumes, for example, multiplied eight-fold between 1997 and 2000.

Under the stewardship of investment bank chief Josef Ackermann, the likes of Mitchell, Jain and Michael Dobson (who was chief executive of the Morgan Grenfell business until 1996) transformed the firm’s wider investment banking prowess. As well as growth in the markets business, underwriting and advisory also put in stellar growth. M&A advisory by transaction value grew by a factor of 13 in five years.

The bank was keen to play its European roots as a calling card to mark it out from the US giants that so dominated the industry at the time.

“It was a time of great innovation and change and what we did right from the beginning was to recognise that of the global players there were very few that had a European flavour. We used that to our advantage, as we set about building dominance in Europe and credibility in the US,” said one insider.

The death of Mitchell in a plane crash at the end of 2000 led to Jain moving up the chain to oversee the global markets operations. He rapidly built on the foundations laid by his mentor, growing debt sales and trading by about a third during his three years as head of the markets division.

By September 2004, Josef Ackermann – who had been promoted to chief executive – appointed Jain and investment banker Michael Cohrs to co-run the investment bank together. The two remained focused on their areas of expertise but brought the two sides of the business more closely together, cross-fertilising revenues and profit.

High point

They inherited stewardship of a business that brought in €13.4bn in revenues. Six years on, when Cohrs retired – and despite a crisis that tore apart the industry – the investment bank brought in a record €20.9bn. The majority of that came from the trading businesses that reported into Jain.

Deutsche was a leading firm in almost all of the business lines in which it competed. It began to be known as the flow monster – a moniker that Deutsche bankers themselves used with pride – as Jain combined what was once a sleepy local markets presence across the globe with its trading and derivatives expertise to capture a huge share of trading and FX flows.

Another significant achievement during that time was the firm’s penetration into the US. Ten years earlier, Deutsche was missing out on IPOs in its own backyard to US giants. But by the late 2000s, it was picking up mandates from the likes of Kraft and Ford.

For many at the firm, the franchise-changing moment came when Deutsche was asked to handle US government auctions of warrants of assets it acquired as a result of TARP. It was one of many government advisory roles that Jain himself led.

“He reminds me of that film Whiplash – he would push people to get the best out of them. It’s a big pond with a lot of sharks and he was better than the rest of them”

The period also delivered huge rewards for shareholders. Regularly pumping in return-on-equity of 20% or 30%, the investment bank (and particularly the trading operation) was the jewel in Deutsche’s crown.

But leverage was a big driver of returns. Low capital requirements – which were optimised by Deutsche perhaps better than any rivals – allowed Jain and Cohrs to more than double the size of their balance sheet during their tenure from €730bn to €1.52trn.

When the crisis hit, major rivals that once inspired Deutsche’s ambitions collapsed or were rescued, with Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch and Bear Stearns all hitting the skids. Deutsche survived without any direct government help. But its wounds – not least a €7.3bn loss in 2008 – were substantial and worse than those of many of its rivals.

Things could have been worse. Jain and Cohrs had taken a decision to drastically scale back risk-taking and to slash leverage before the crisis hit. The credit prop desk was closed towards the end of 2008 and the equity desk went the same way in 2010 – brave calls considering how much money those businesses made.

Hard times

Times quickly became harder – not just for Deutsche, but for the industry in general. The firm’s immense balance sheet made adapting to the new world harder than it was for most, as did its focus on trading operations, which became the focus of a regulatory crackdown by authorities scornful of what they called casino banking.

During that time, however, Jain – who by 2012 had taken over as group co-chief executive alongside Juergen Fitschen – never lost sight of wanting to be the last remaining full-scale European investment bank.

That vision, which wasn’t shared by all of the board or shareholders, ultimately led to him stepping down. But with most European rivals having fallen by the wayside or having pulled back substantially, Jain leaves behind a legacy of Deutsche being the only European bank that can truly say it fights toe-to-toe with the major US investment banks across almost all products.

“He built that business from nothing – he created the Goldman Sachs of Europe,” said one person who worked closely with Jain. “He might have been tough but you don’t become head of an investment bank without making a few enemies – it’s a cut-throat profession and he was incredibly good.”

“He reminds me of that film Whiplash – he would push people to get the best out of them. It’s a big pond with a lot of sharks and he was better than the rest of them.”

Jain left his job as co-CEO on Tuesday. He will continue to advise the board for the next few months.