European securitisation comes in from the cold: regulators are finally warming up to a vital market. What are its prospects now?

To see the full digital edition of the IFR Top 250 Borrowers Report 2014, please click here.

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email gloria.balbastro@thomsonreuters.com

Securitisation, the cunning wheeze of wrapping up various types of assets and debts into packages that made millions for bankers in the last decade, but exacerbated the subprime mortgage crisis that fuelled the financial meltdown, seems to be back in favour as central bankers see that it still has an important role to play.

Companies have faced a financial drought as European banks scaled back their lending to business in response to both the need to deleverage their balance sheets and the Basel III regulations on capital requirements. But a Who’s Who of policymakers in Europe are now lining up to call for regulators to revive securitisation and get money to SMEs as part of efforts to kick-start economic growth. Is going back to the future a positive idea or a case of memory failure?

One of the loudest voices has been that of Jacques de Larosiere, the former head of the IMF, who this May called for a “safe” securitisation market in which national central banks could buy securities.

In May last year, Mario Draghi, president of the European Central Bank, unveiled plans to develop initiatives to promote a functioning market for asset-backed securities collateralised by loans to non-financial corporations.

And he followed this at the recent (June 5) meeting by saying that preparatory work for ABS purchases was intensifying, but fell short of providing any concrete details except that the assets must be in the real economy (no derivatives), simple (no complex collateralised debt obligations) and transparent (full disclosure of information).

Little has actually happened to get the money flowing, though, and businesses are still facing a shortage of finance. One factor may be that regulators are nervous about returning to a market that caused such damage.

Don’t use the ‘S’-word

“Anything with the S-word in it got blamed for causing most things to do with the crisis, one way or another, whereas history and statistics largely show that securitisation involving the major asset classes – other than subprime and CMBS – in many markets performed just fine and there was no meaningful movement of the needle in relation to defaults relative to what they had been before,” said Marcus Mackenzie, a partner in the finance team at global law firm Freshfields.

According to Standard & Poor’s, the cumulative default rate on European structured finance assets from the beginning of the financial downturn in July 2007 to last autumn was 1.5% – and was just 0.4% for SME collateralised loan obligations.

Nevertheless, new issuance of securitised products across Europe has slumped from a peak of more than €800bn in 2008 to less than €200bn in 2013, according to the Association for Financial Markets in Europe (AFME). But by 2009, almost all new deals were retained by the originating banks – rather than bought by real investors – and many were placed as collateral with central banks to gain access to liquidity. The amount outstanding has dwindled too, from around a peak of €2.2trn in 2009 to €1.5trn in 2013.

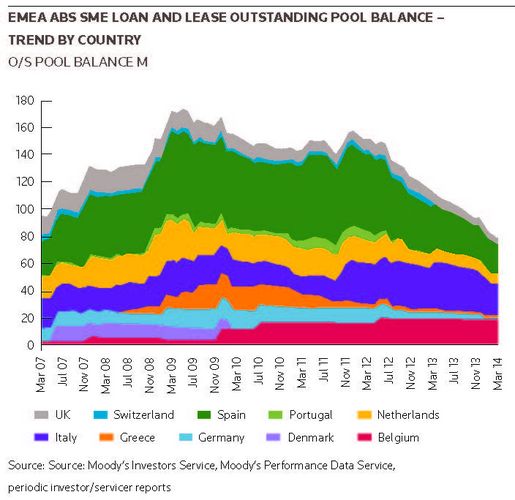

The much smaller SME asset-backed securities market has also shrunk, from a peak of around €180bn in 2011 to €108bn by the first quarter this year, according to AFME.

However, there are signs that real investors are returning to the market, according to Thorsten Klotz, managing director of structured finance at Moody’s.

“For the first time we are seeing some discussions about how this could change and whether real-side investors could buy SME tranches,” he said.

“We are seeing a lot of activity in Italy across the board, including SMEs, and we are starting to see activity in Spain, Ireland and Portugal, but at much lower levels. Compared with the pre-crisis markets, there has been a subtle shift.”

According to many analysts and policymakers who believe securitisation is the answer to a shortage of funding for businesses, it is the regulatory system that is really to blame for the lack of real momentum in the market.

In April, Draghi and his British counterpart Mark Carney criticised the “unduly conservative” approach by regulators towards asset-backed securities in a rare joint statement on what they called the “impaired” EU securitisation market. They then followed up with a more detailed paper in May.

”One of the ultimate frustrations is that you get all the nice warm words from all sorts of important people in the market talking about securitisation very much needing to be part of the funding tool in the toolbox”

While acknowledging some positive steps, such as establishing a risk retention rule to ensure originators of ABS retain some “skin in the game” and measures to increase the transparency of the structures, they said regulators had failed to distinguish between safe ABS and more opaque products.

According to Mackenzie, the problems go deeper. The regulatory reforms have led to a myriad of different rules in different jurisdictions that mean an identical transaction can be viewed differently in two member states.

“There are anomalies and imperfections in the regulatory environment that continue to shackle the development and use of the product in a way that will bring back investors in the numbers that are required to fill the funding gap that people perceive to be out there,” he said.

“One of the ultimate frustrations is that you get all the nice warm words from all sorts of important people in the market talking about securitisation very much needing to be part of the funding tool in the toolbox.”

AFME, which represents leading European banks and capital market players, has called for a number of regulatory reforms. These include recalibrating the risk weightings for high-quality European ABS, lower capital charges for insurers holdings ABS under the Solvency II rules, and the inclusion of SME loans as high quality assets for the liquidity capital ratio rules that govern banks.

“Europe risks sending mixed signals to the market,” said Simon Lewis, AFME’s chief executive. “It is clear that time is running out for the positive regulatory signals needed on the LCR and Solvency II.”

Strict regulatory controls that increase the cost of holding SME-based assets means banks that hold SME loans are unlikely to use them as collateral because they will trade wider in the market than those based on unencumbered mortgages, auto loans or credit cards.

Christian Schulz, a senior economist at Berenberg Bank, said that in order to create deep and efficient markets for such SME ABS, European and national development banks would need to play a role in packaging, certification and guarantees. This was on top of the role the EU must play to define and regulate products.

But he pointed to a 2004 German initiative, known as the True Sale Initiative, which has only done 80 transactions in a decade, partly because it was a complex process involving many banks, the public development banks and government regulation.

”Europe risks sending mixed signals to the market. It is clear that time is running out for the positive regulatory signals needed on the LCR and Solvency II”

“Ultimately it is all about risk and transparency. It was difficult at the German level and will be even more difficult at the European level,” Schulz said.

Increased transparency of asset performance, transaction documents and cashflows associated with deal structures would help investors assess the credit risk of ABS, an aspect of particular importance for investors in the riskier junior tranches of securitisations.

Chris Barratt, a partner at Freshfields, said the European Commission and Parliament needed to enact legislation to replace the different regimes across the 27 member states.

“The Commission and EU legislators need to respond sooner rather than later if they genuinely want to revive the market and funding for SMEs,” he said. ”They have created the beast but they need to tame it.”

One potential breakthrough could be the creation of “high quality” securitised products that could benefit from a more benign regulatory treatment.

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and the International Organisation of Securities Commissions are examining this and Carney and Draghi have thrown their weight behind it, acknowledging that the key issue is the criteria that distinguish high quality transactions from the wider ABS universe.

Moves towards opening the market may have been dealt a minor blow by the May 25 European elections, although most analysts believe it will not cause too great an upset.

“I have no doubt that any agenda will have growth and financial stability as a core part,” said Barratt. “If they want growth and financial stability and security, continuing the themes of looking at what’s in the market and implementing changes to certain regulations … will be part of any parliamentary agenda.”

Looming hurdles

A successful purchasing programme focusing on ABS purchases would face numerous hurdles.

The most obvious is that the outstanding ABS market itself is simply too small, and the proportion backed by SME assets minute. According to Barclays, there is €110bn of SME ABS outstanding, of which €13.3bn is placed with investors “and would theoretically be available for secondary market purchases”.

Moreover, were the ECB to buy exclusively Triple A tranches, only a “significantly smaller amount ranks senior in the capital structure”, Barclays analysts said in a report.

If the central bank focused on buying RMBS that would bring the amount of paper “immediately available for purchase” to €330bn, according to analysts at Brussels-based think tank Bruegel.

The regulatory backdrop is still identified by many, including Draghi himself, as the main battlefield for any restoration of the ABS market. Asset purchases without regulatory changes may only prove partially effective.

Draghi said there needed to be a review of regulations to eliminate some of the undue discrimination, reiterating a point raised in the joint paper published by the ECB with the Bank of England on May 30.

Analysts still argue that, even in the event of ECB ABS purchases, the pricing disparity between ABS and other markets would continue.

“Investors require senior ABS to provide a higher return than comparable investments” such as covered bonds, Barclays analysts said. That “regulation yield premium” is driven not only by higher capital charges and haircuts, but also by higher operational requirements for investors.

“The penalty would not necessarily reduce if the ECB became an additional buyer of senior bonds,” the analysts said. “As a result, senior securitisation would likely remain a relatively expensive funding source for banks.”

Anna Brunetti