The 30th anniversary of Big Bang has come at an opportune moment.

The dramatic set of regulatory reforms that took effect on October 27 1986 certainly revolutionised the workings of the UK’s closed-shop financial sector. But why is this particular anniversary so timely? Well because there’s a lot of chatter out there today about whether the UK is about to face a revolution of similar proportions as the British government prepares to navigate the treacherous waters of exiting the EU.

Want a concise history of exactly what happened in the run-up to and during Big Bang as domestic and global players girded for battle? Take a look at the attached table I painstakingly researched, recalled and compiled. It’s history in a table; the story of a fractious and frantic financial industry revolution.

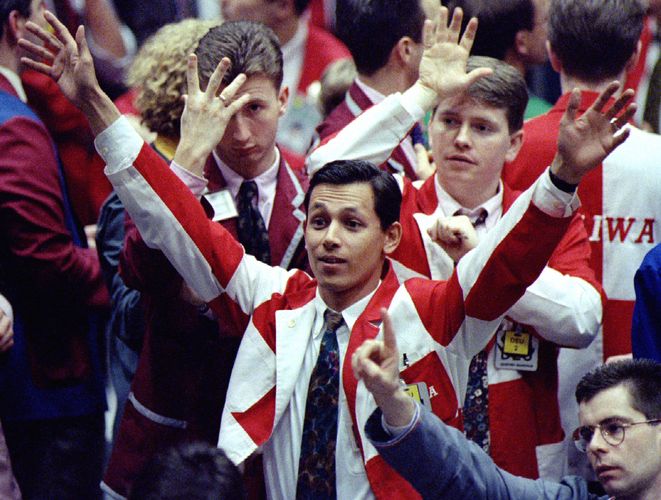

As well as delighting in the absorbing detail of this incredible history at a firm-wide level – I’ve tracked the takeovers of 68 brokers, traders, investment banks and Treasury bill dealers (aka discount houses) – take a step back from the intrigue of each and every takeover situation. Try to imagine the electricity in the air as hundreds of dances and dalliances were taking place and then imagine the impact of dozens and dozens of hurriedly-arranged simultaneous marriages on a system that wasn’t prepared for the new cast of characters, let alone the dramatic changes wrought by the reforms.

Could we be about to witness the benefits of Big Bang coming full circle and turning in on themselves? The City of London finds itself at a fascinating if nervous point in its long history. If the term Big Bang evidences an explosion, and one that in this case cemented London’s position as the world’s pre-eminent financial centre just as financial market globalisation as we know it today was still emerging, are we about to confront an equal and opposite implosion?

As armies of market professionals ponder setting sail for pastures new depending on the outcome of Brexit negotiations, might that implosion bring with it a period of chaos and disorder that ultimately sees London stripped of its pre-eminence to become a domestic service centre in something of a shift back to the way we were?

I don’t mean a shift back in the sense of going back to fixed commissions or re-introducing a separation between broking and trading. Or obviously going back to paper share and bond peddling. Nor, perhaps more pertinently for today, do I mean re-introducing a ban on foreign ownership of UK brokers – although in the squalid minds of those riding the grubby wave of jingoism-cum-xenophobia that has emerged since the UK’s referendum on EU membership I suspect that might get widespread support.

I’m referring more broadly to the potential return to a more UK-centric status quo where UK-based global players have lost passporting rights to operate across the EU and over time have drifted away leaving skeleton teams in place. Where London has become the hub for … well … the UK, and where global in the UK context means transacting globally in UK securities and advising UK clients and clients who require UK access. This more filleted dimension of globalisation or even regionalisation puts an altogether different and arguably less appealing complexion on the debate about the future of London as a financial centre.

No paragon

So much has been written about Big Bang and its legacy over the past 30 years. I was already well ensconced in the world of financial journalism by 1986 and I had been a keen if sometimes baffled watcher of the ways and workings of the City. With apologies to the smart people behind the millions of words that have been written on the subject, here’s my potted summary.

First of all, the notion that has been bandied around for years of foreign predators coming in at Big Bang and shaking up the cosy workings of the City is grotesque, given the multicultural nature of the City’s origins and particularly now given the temperature of the current political debate. I similarly reject the notion of Big Bang having sown the seeds of financial market Armageddon in 2007–2008; of leading us into the short-term bonus culture that took the system down; of introducing cultures that in effect turned a blind eye to misconduct in the pursuit of short-term profit. Nothing but tawdry revisionism.

The City had hardly been a paragon of righteousness. It’s often referred to as cosy club. The City was, beyond so many fine things, an alcohol-tinged den of inside information and nod-and-a-wink dealing run by aristocratic dynasties and the closed ranks of Britain’s upper classes alien to the concept of meritocracy and ill-suited to the onset of open competition, big-ticket institutional deal flow and its capital requirements.

The very fact that Big Bang was enacted in order to side-step an anti-trust suit centred on restrictive trade practices rather than the result of a decision to open up in the spirit of open competition to all-comers tells you all you need to know about how it worked.

Rogue behaviour was hardly invented by Big Bang. And as for compensation, partners of old-line City banks and brokers did OK. I read somewhere that as many as 1,000 well-heeled denizens of the old City may have walked away with £1m each on average as a result of selling out their partnerships to domestic and international acquirers who got caught up in the heat of the moment and ended up overpaying to get their sign over the door. What price heritage? Well, about US$3.5bn in today’s money it would appear…

Was Big Bang a success?

Then as now, success didn’t come from the mere fact of having a London presence. Take another look at my table and assume that at least half of those takeovers ended in disaster and ignominy, and not just as a result of the stock market crash of 1987. As much as the dizzying takeover circus in the run-up to October 27 1986, Big Bang should be remembered for the failed adventures, the broken dreams, the billions of pounds lost, the mis-management, the shutdowns, the break-ups and the fire-sales.

So many Big Bang takeovers have spawned multiples of themselves over the past 30 years and it’s still going on. Whole businesses have been re-bought and re-sold, in some cases multiple times over; so many businesses have been split into component parts and sold to different owners, be that private-client stockbroking, institutional securities, banking, or investment management. City brands have been bought, mothballed, sold, and re-introduced. Some brokers have regained their independence after decades of being run by multiple - and in some cases clueless - owners.

Big Bang was certainly a double-edged sword in so many ways. But if London now risks giving up one enormous benefit – its global hub status – where does that leave the institutional fabric of the City? Global banks have actively modelled Brexit options and the future of their UK campuses and have contingency plans in place. Big banks are similarly embroiled in the not inconsiderable task of cutting costs and headcount to boost returns.

Depending on political and monetary outcomes, it could all unravel quite quickly. There’s a decent-sized group of very competent and focused UK brokers plying their trade in the domestic market. Could they about to have their day in the sun?

And will the ‘Big Bang 1986’ chapters in countless text books be followed by chapters on ‘Damp Squib 2016—2019’? As ever, answers on a postcard.