Would you like to consolidate your existing debts into one nice, easy payment with a low, low rate? Wouldn’t we all? Chinese provinces are certainly keen, and have been queuing up one after the other over recent days to swap their huge piles of expensive bank loans into bonds with much lower interest rates as part of a new government initiative.

The bonds-for-loans swap scheme was announced amid much fanfare in March. But a standoff between Beijing and the country’s largest banks, clearly unhappy at being strong-armed into giving up tens of billions of renminbi of annual interest payments, delayed any prospective deals for a good two months – until the banks backed down.

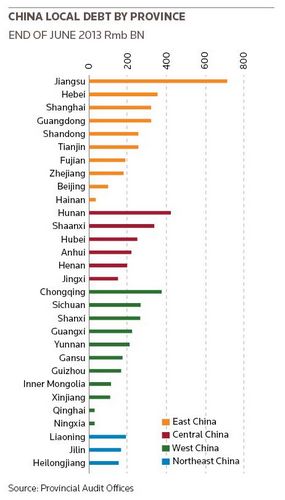

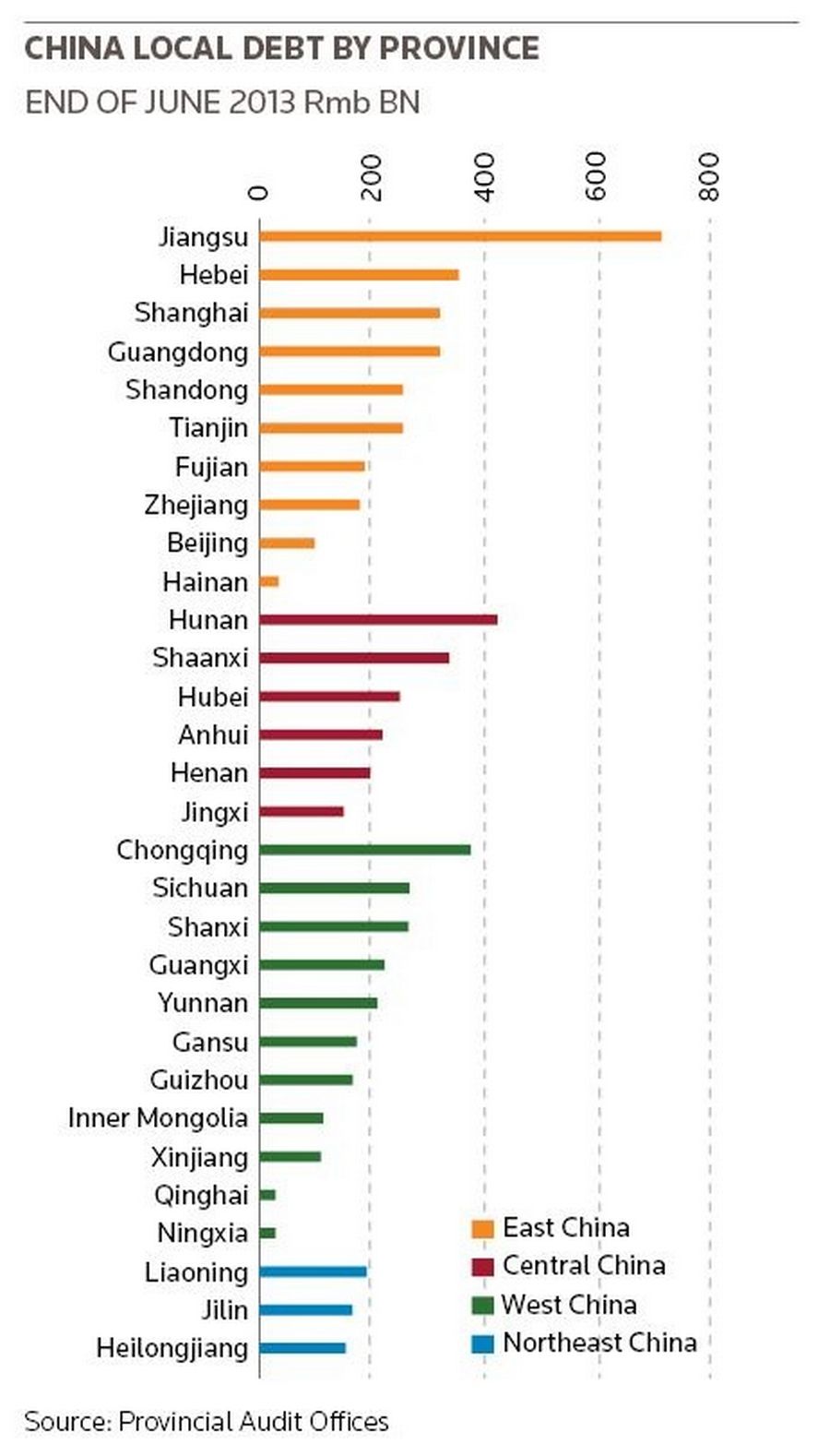

With banks now begrudgingly onboard, provinces are rushing through deals like there’s no tomorrow. Jiangsu, home to the former imperial capital Nanjing and one of the smallest but most indebted of all China’s provinces, printed the first on May 19 – and was soon followed by Xinjiang, Hubei and Guangxi, all keen for a bit of debt consolidation of their own.

The Rmb98.1bn (US$15.8bn) of bonds issued in just a few weeks is only the beginning. The Ministry of Finance has told provinces that Rmb1trn of bank loans can be swapped into bonds this year alone. It will also allow provinces to issue another Rmb600bn of bonds on top of the swaps.

It is expected the scheme will be extended beyond this year, in what will be – in effect – a slow, backdoor restructuring of regional government debt.

Looking at the deals done so far, it is clear to see why the bonds are so appealing – at least for provinces. The sector is facing a huge refinancing cliff, with nearly half of its Rmb10.9trn of debt coming due over the next 18 months. The swaps guarantee they can roll over debts – and pay a much lower rate than at present, making the mountain that much more manageable at a time of falling revenues for many regions. “This will cut our interest burden in half,” Jiangsu officials boasted at the deal launch.

Raw deal

Banks, on the other hand, are getting a raw deal – and they know it. The low interest rates on the new bonds seem to have been the main sticking point that led to the standoff. Banks, which are expected to buy a big chunk of the bonds, will receive just a fraction of the interest they used to get. Beijing is playing the role of a twisted Robin Hood, taking from the banks to give to the poor old provinces (although given that the former are largely state-owned and the latter simply part of the state, it could be seen as a simple book-keeping exercise, albeit one in which minority shareholders in the banks are hurt).

Just to rub salt in the wound, banks have clearly been forced to stomach returns well below the market rate. Ratings agency Standard & Poor’s caused uproar last year by saying that half of the country’s provinces merited junk status, but with high debt-to-GDP ratios and falling revenues, S&P was right. Rather cheekily, the government has ordered banks underwriting the new bonds to price them tightly against China’s sovereign bonds (S&P rates China at AA–). Banks have duly done as they were told.

In the days after the deals printed, the secondary market has shown precisely what it thinks about the pricing of these bonds. Many haven’t traded at all – private investors are clearly giving them a wide berth – while those that did trade have tanked. Jiangsu’s 10-year bond, issued with a 3.41% coupon, has plunged almost three points in the first days of trading – a major drop in bond markets, and usually a sign underwriters got it wrong. The bonds were bid at a yield of 3.75% on Wednesday.

Government pressure

The banking industry clearly buckled under government pressure. That is perhaps unsurprising, given the clout of both the central government, but also of the provinces themselves. The latter are important clients, providing a whopping Rmb18.5trn of deposits. Add to that countless fees linked to wage and bill payments, as well as the financing, hedging and advisory business that banks do with regional governments. The customer – especially one the size of a Chinese province and backed by Beijing – is always right, even when the interest rate they demand is so obviously wrong.

But these deals are more than just a case of lost profits for the banks. By forcing the underwriting banks to print bonds with coupons well below the market rate, Beijing is effectively giving up on creating a new investor base for the Rmb10.9trn of provincial debt. Beijing clearly expects banks to be the main – and potentially only – buyer.

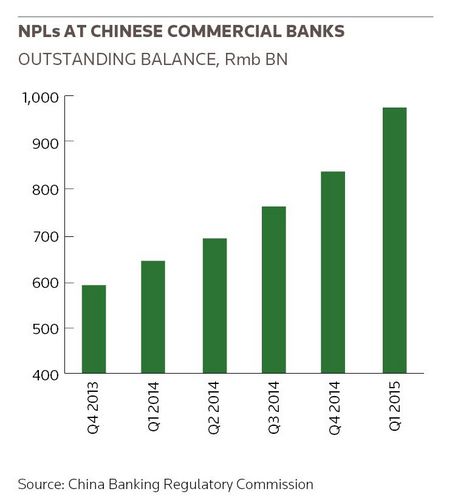

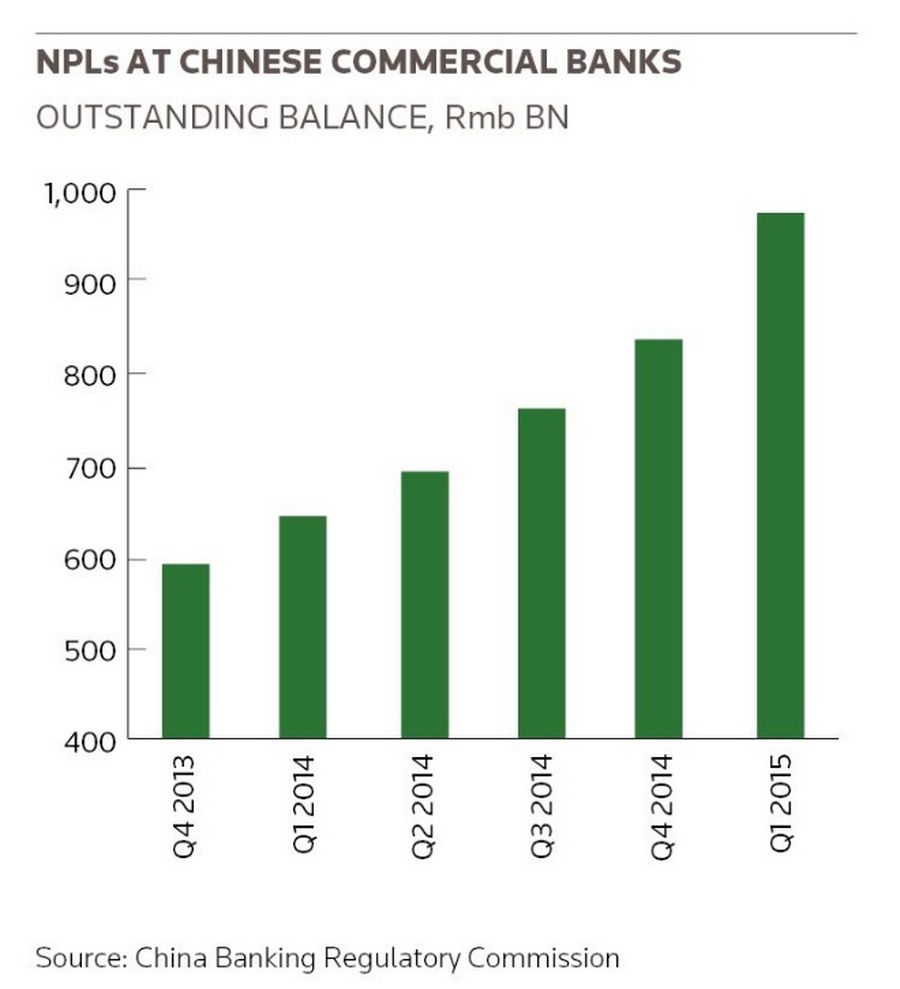

This is a dangerous path to take. Banks are clearly already under strain: with the economy slowing, non-performing loans have risen by more than 50% over the last year alone to Rmb983bn. The industry is beginning to become cautious, and is putting more aside as provisions, diverting valuable resources away from lending to SMEs and retail at the time the economy perhaps needs it most.

Banks extended just Rmb708bn of new loans in April, well below the lowest-in-the-range forecast from analysts of Rmb800bn. Broad money M2 annual growth of 10.1% in April was the lowest since records began. Things are likely to get worse: Nomura says Chinese banks face a “triple witching” of falling profit margins, rising NPLs and about Rmb770bn of fresh capital that needs to be raised. It says no major banking system has faced such a confluence of challenges in the recent past.

Creating a new private investor base for provincial debt would have freed up bank resources to lend at more profitable levels and that would have in turn have helped generate capital faster. Instead, banks are being asked to roll over Rmb1trn of loans at low rates, which will constrain their ability to generate capital. What is more, with the additional Rmb600bn of bond issuance, banks are implicitly being asked to increase their lending to the provinces. Many will have to cut lending elsewhere to do this.

Concessions

The industry did win one concession during its two-month standoff with Beijing, winning permission to use regional government bonds in repo transactions at the central bank. That will be helpful, but it is unlikely that banks will use the cash generated from these repos to lend – the maturity mismatch makes that unappealing. Just look at Europe, where only 5% of the European Central Bank’s longer-term refinancing operations – a big repo – generated direct lending to the wider economy.

Reducing debt servicing costs for local governments will make that debt more sustainable, but it comes at a cost for the wider economy: it will make it harder for the big commercial banks to generate capital, and will starve other parts of the economy of credit.

The People’s Bank of China is worried about what this means for the wider economy, and it should be. Governor Zhou Xiaochuan, speaking at the Lianghui meeting of the ruling Communist Party in March, warned about less efficient companies taking up far too much of the economy’s resources, squeezing out SMEs. Leaning on banks to prop up provincial governments won’t help fix that problem. China needs to rethink its bonds-for-loans swaps to ensure lending to the private sector doesn’t dry up.

gareth.gore@thomsonreuters.com