The unanimous decision by the US FOMC – presided over by new Fed chairman Jay Powell – to raise the target range for Federal funds by a quarter point to 1.50%–1.75% on March 21 kept the juggernaut of tighter US money firmly on the road. Europe and eventually Japan will follow. In the meantime, prepare for shifts in fund flows, crowding-out effects and volatility.

The corollary of a fully globalised and interconnected financial system is that markets can be made or broken by capricious and super-sensitive global capital. Those prodigious pools of capital are pondering a lot of issues at the moment. There’s a lot on the radar and they’re worried.

About how durable the US recovery is. About how markets deal with a US-Europe-Japan economic and monetary scenario that is still moving at different speeds but where there’s better alignment around the path to normalisation. About what happens to asset valuations domestically and across and between regions and asset classes, from fixed income and currency markets to equities, alternatives and emerging markets, as the Fed moves along its tightening path.

About what happens in the event of a trade war. Will China use its position as the largest foreign holder of US Treasuries (US$1.17trn at January 2018, almost 19% of all foreign ownership) as a weapon in a simmering trade war just as the Fed need to ramp up debt issuance? Or will the imperative to keep the renminbi competitive be a greater impulse?

Then there’s Brexit and Euroscepticism; the rise of political populism not just in the US but in Europe (witness the March 2018 Italian elections) and the uncharted territory of unorthodox policy outcomes; the rise of anti-globalisation, anti-free trade sentiment and its impact on terms of trade and global flows. Geopolitics remain a constant threat.

Market insecurity

Taken in the round, this demanding set of circumstances is causing a lot of head-scratching and creeping insecurity. Markets have succumbed to bouts of asset price volatility and are skittish. There is palpable uncertainty about the quantum, nature and direction of capital flows; how this affects global bond yields and yield curves; what happens to credit spreads and what will cause what many see as the equity bubble to burst.

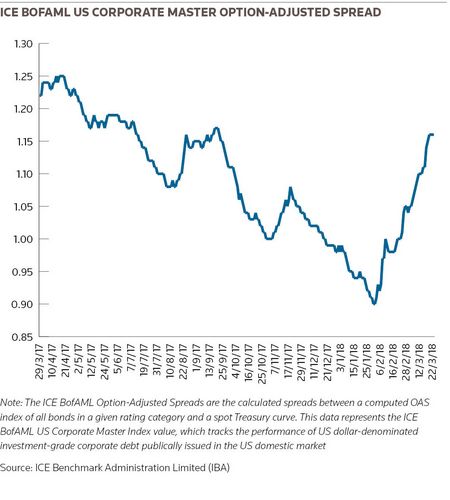

Sky-high confidence levels in the capital markets are on the wane in 2018. Investors have exhibited clear signs of selectivity, resolutely pushing back on aggressive pricing and deal structures in credit markets. The shoe is shifting to the other foot. Oversubscription levels in primary bond issues have reduced as complacency gives way to concern. Spreads are wider.

“The peak benefit of global QE is behind us and we are inching our way to normalisation at a global level. Markets have become accustomed to huge liquidity stimulus over nearly a decade; taking it away will result in meaningfully higher rates,” said George Goncalves, head of US fixed income strategy at Nomura in New York.

“The question is not so much what this does to the bond market; what matters more is what it does to competing asset classes. We’re still at an early innings but are on track to go above 3% in the US 10-year over the course of this year as a result of the combination of less global QE, the Fed running up against some really large fiscal deficits and deficit spending from the Federal government. That’s the perfect cocktail to push up the overall level of rates to a level which will start to compete with other asset classes.

“The extra supply we don’t usually get at end of the business cycle plus QE going away will expose the fragility of many asset classes, including equities. Higher overall rates in government bonds are already stealing some of the thunder from investment-grade bonds, which have not done well this year as the market works its way towards a crowding-out effect,” Goncalves continued. “The Treasury market will always fund; it will just be at a different price. But it is competing for dollars with other assets. This will drive a shift towards a more domestic buyer base for US Treasuries and at the same time displace private capital formation.

“On the investor side, the higher we get on rates, some of the big portfolios will have to book mark-to-market losses that will limit their risk appetite. At a certain point, that starts to disrupt the business cycle and can actually be an offset for positive growth factors that are trying to be enhanced through fiscal stimulus.”

People are nervous about the psychological 3% level for all sorts of reasons, including what it does to the nation’s debt-servicing costs – both public and private sector. Of course, as bank rates creep higher and the Fed balance sheet shrinks, investors – and that includes foreign investors – have an alternative they did not have before: they can hold cash at the banks. That will push domestic banks to gravitate more fulsomely towards Treasuries, though, particularly as the Fed floods the system and crowds out lending opportunities.

Dancing to its own tune

Washington is dancing to its own tune and dealing with a strengthening labour market, strong job gains/low unemployment, and inflation expected (by some, though not all) to move closer to the Fed’s 2% target over coming months. Standing by to see what happens as the dust settles is not an option because the dust won’t settle here. The March rate rise will be followed by two if not three additional rate rises this year, with further moves over the next two years. The US has entered its own monetary channel.

And it’s not all about monetary action. The US tax bill has put US fiscal accounts and public spending firmly under the spotlight. How the interplay between monetary and fiscal poles plays out in the trenches of financial markets as the twin impacts come into view is subject to some uncertainty. The US Congressional Budget Office and Joint Committee on Taxation reckon the tax reform will add US$1.455trn to US national debt over the next 10 years. This is not trivial.

So what can the markets expect for the year ahead?

“The Fed currently has an extremely high degree of credibility in regards to the market’s reaction to its telegraphed hikes. The gap between median expected hikes and the pricing of those hikes via the futures market has narrowed to almost zero,” said Ian Lyngen, head of US rates strategy for BMO Capital Markets.

“While 10s feel the impact of bumps to the target rate, they do so to a much lesser extent than other sectors of the Treasury market. What will be more impactful for 10-year yields is the broader economic outlook. We see 10-year yields driving lower when the seasonality of market optimism and several fiscal variables are left behind as we move later into the year.”

This, Lyngen adds, includes the effects of the tax bill, which he believes have largely been absorbed by the market. The same holds true for the borrowing needs of the Treasury, which is reflected in issuance size increases across the curve, though with a narrower focus on the front end. However, similar to the tax bill effects, he reckons those increases have already been digested by the market.

The psychological 3% barrier

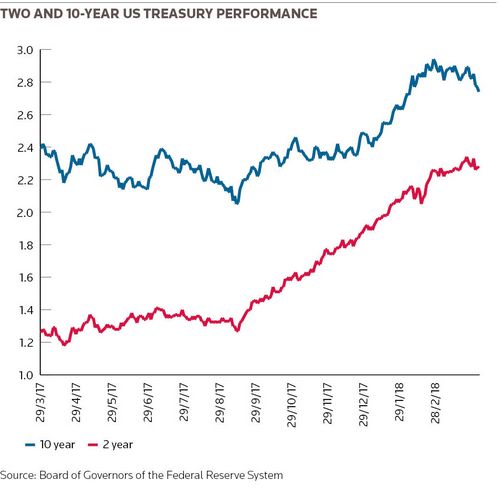

Despite a sincere attempt to breach 3% in 2018 – the 10-year hit 2.954% on February 21 – the yield has bounced decisively lower and was at back 2.74% on March 29.

“This is a trend we see continuing throughout the year as data and the realities of the economy sink into the market. While short-term forays to higher yield territory are not out of the question, ultimately we see 10-year yields moving lower,” Lyngen said.

Guy Stear, head of fixed income and currencies research at Societe Generale sees things a little differently.

“With the growth situation and headline inflation pressure relatively limited, I don’t think we’re likely to break 3% then move rapidly higher, but I do think we will see a move through 3% on the back of continuing signs of underlying inflation pressure and the need to find new buyers for the Treasury market,” he said.

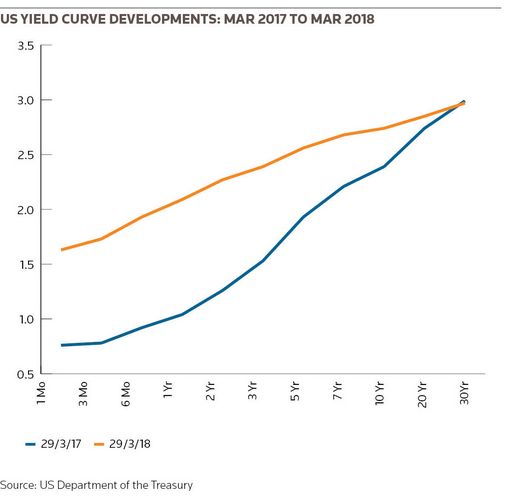

Stear is in the camp of three rate rises this year. But that, he says, is not so much the issue. “The concern in 2018 will be whether we are seeing underlying inflation pressures picking up in terms of the wage cycle in particular and what kind of a response that provokes from the Fed not just in 2018 but in 2019. In terms of curve developments, we expect steepening at the front end since interest-rate expectations in the three to five-year area still need to be going up, and in terms of rising yield potential this is the most sensitive area.”

Like Goncalves, Stear believes there will be impacts on other markets. “As new buyers have to be found for the Treasury market, what really suffers are ancillary fixed income asset classes. We have already seen this on corporate bonds, which have witnessed a sharp rise in spreads in the three-year area as increased Treasury bill issuance has sucked demand from credit,” Stear noted.

He expects outflows from global credit funds to continue. Starting with US high-yield, moving to investment-grade and then Europe, there have already been reversals.

“These haven’t been substantial at this point but I expect they will continue. There are two ways investors can move money out: they can generally not like fixed income including credit and move into a combination of equities and cash, particularly cash.

“Or they decide that sovereign yields are high enough so they don’t need the extra spread that credit provides so they rotate out of credit into sovereigns. This is more of a threat. Switching out of fixed income is a more difficult asset allocation decision, so will typically take longer. Moving money within fixed income can happen very quickly.”

Year-end prognostication

So, bearing in mind Fed rhetoric and market expectations, what should we expect to see in the US by year-end? Ian Lyngen sees an inverted yield curve as the Fed continues on its path toward higher rates.

“While optimism and a hawkish demeanour are expected at this point in the year, we believe the data and material impact of higher rates on the real economy will cause cracks to appear in the otherwise positive picture,” he said.

“We remain sceptical of inflation’s return and would caution investors to focus on the details of inflation metrics. Another nuance of this debate is whether inflation’s return would be due to demand push or supply pull. This dynamic will continue to be a crucial variable as the Washington policy whirlwind continues. The effect of the broader protectionist policies from the Trump administration will eventually trickle down to the consumer and in turn the real economy.”

He adds that if the first few months of Fed rhetoric under Jerome Powell are any indication, we will likely continue to see broad-based economic optimism and data points that are not weak enough to derail the Fed from its hike path, which has already shifted in 2018 from ‘two maybe three’ to ‘three maybe four’.

“We expect this trend to continue and the curve to flatten as the Powell Fed marches on in its 25bp-a-quarter tightening pace. This tightening, coupled with tapering, will have a material impact on the economy as the cost of borrowing rises. We expect these effects will be abundantly evident by the end of the year.

“As the Fed continues to hike in the face of what will likely be less-than-stellar economic data, as well as inflation that could fail to materialise in earnest, we see the flattening of the curve causing credit spreads to widen over the course of the year. Rising rates in the front end will cause investors to demand more yield relative the respective benchmark rates.”

Meanwhile, two steps back…

In Europe, more than the future direction of policy rates, the issue of most significance to market participants is the fate of the European Central Bank’s asset purchase programme and how the region’s biggest investor starts to exit a programme that for all of its putative benefits as extolled by ECB president Mario Draghi has distorted primary and secondary capital markets valuations across the asset classes in which it is active.

On rates, Draghi has pledged to keep key interest rates at their current levels well past the end of net purchases “to ensure”, he said in a speech in Frankfurt on March 14, that “policy stimulus is not undermined by premature expectations of a first rate rise”.

The ECB has recalibrated its asset purchase programme, which has shown up clearly in the ebb and flow of market operations. In that March speech, Draghi said the monetary stance is “tuned to the changing pitch of the recovery” and the drive towards the 2% inflation target.

Draghi has certainly been emboldened by stronger economic signals: capacity utilisation in capital goods near all-time highs; recovery of all the job losses suffered during the global financial crisis; corporate and household indebtedness back at early 2008 levels; higher confidence levels; and rising business investment.

Risks and uncertainties remain, however, and the ECB is alert to items such as lacklustre housing investment and discretionary household spending, which get in the way of the core aim of maintaining a sustainable path towards the core inflation target. It is that target which will determine the asset purchase programme’s ultimate horizon.

The ECB is clear: only when this is deemed sufficient will net purchases come to an end. Even after that it will control financial conditions through its reinvestment policy, which will ensure a continued market presence after net purchases expire. Just to give an idea of the numbers involved, redemptions under the APP between March 2018 and February 2019 are around €167bn. Reinvestment amounts, the bank said, will remain sizeable thereafter.

BMO’s Lyngen believes Draghi’s comments in March were an attempt to create a soft landing for investors in terms of the realisation that European QE cannot continue ad infinitum.

“As the ECB embarks on the path to normalising monetary policy, the impact on the market will depend on their ability to remove accommodation without being too aggressive and becoming detrimental to the European economy,” he said.

What happens when buying ends?

So, what happens when the ECB stops buying? Goncalves says the US has benefited from low European rates and has seen a lot of European buying.

“From the perspective of the spill-over effect back to the US, that should reverse direction over time, leading to the formation of home country bias as yields go up enough to incentivise local capital to stay at home rather than chase yield overseas,” he said.

“By and large, yield levels globally are in the wrong zip code. Taking a big captive buyer away, I would hope market forces demand a premium, so you should see an adjustment there. The ECB’s saving grace is Europe doesn’t have as huge a fiscal overhang as the US, making it easier to transition away. Ending QE in Europe doesn’t have to be a replica of the US taper tantrum.”

SG’s Stear points out that even though the ECB has reduced its bond-buying programme, there has been an acceleration of gross issuance on the sovereign side in particular, leading to some fairly hefty deficits and rising levels of debt.

“The probability is when the ECB stops buying you’ll see an upward translation in terms of the yield curve, probably driven by the five-year area. That’s in part because of supply needs. But what’s possibly going to have a bigger impact isn’t finding new buyers but people starting to anticipate what happens when the ECB increases interest rates. It’s probably the second factor that’s going to dominate.

“One of the things that has tended to happen as the ECB has reduced its programme is they’ve done a larger percentage of corporate bond purchases. I think we’ll see a crowding-out effect on the corporate bond market. Some of the net new demand that will have to come for the sovereigns will come from corporates and other fixed income assets, so we will probably see pressure on the corporate market and on semi-sovereigns,” Stear said.

BoJ stirrings

If Europe is on track to hit its economic and monetary goals but some way back from the US, Japan is further back still. But speaking at the beginning of March, Bank of Japan governor Kuroda – reappointed for a second five-year term starting in April 2018 – stunned market participants when he said the BoJ might exit its ultra-loose monetary policy if it hits its 2% inflation target in fiscal 2019 (ending March 2020).

That was the boldest statement of intent since the onset of its programme of quantitative easing and created another key market imponderable: to what extent will the BoJ start to cut back on asset purchases in the run-up to fiscal 2019 or change its stance around yield targeting as a way of kick-starting interest rate normalisation in parallel with moves towards the inflation target?

As of March 20, the Bank of Japan held almost ¥414trn (US$3.9trn) in Japanese Government Bonds. Market participants have been intently watching what they refer to as the central bank’s ‘stealth tapering’, a reduction and subtle shift in bond buying patterns – particularly at the long end – that has fed a sense of enhanced unease about a potentially modified stance – even as the –0.1% overnight interest rate and 0% 10-year JGB yield remain intact as part of the BoJ’s yield curve control programme.

There is a broad consensus for a status quo in Japanese monetary policy; a second Kuroda term is a vote for continuation.

“Inflation concerns will assuredly remain as the BoJ maintains its wait-and-see policy in regards to its exit from QE. But it would not be out of the question for Kuroda to make a Draghi-esque attempt at laying out the mat for a soft landing. But a more convincing return of Japanese inflation would be the pre-requisite for that to occur,” Lyngen said.

SG’s Stear agrees the BoJ will react slowly. “What they want to be is the most dovish central bank so we’ll see the slowest return to normalcy in Japan. The currency is an issue and will push the BoJ to be dovish for longer, independently of what’s happening domestically. Kuroda is constrained in policy terms by the need for normalisation elsewhere.

“What’s worrying Japan the most is what happens if the US economy starts showing signs of being past its peak in growth and starts to slow. If you look two to three years out, you might end up with monetary policy that is not as hawkish as the Fed might want to believe at the moment. What pressure does that put on the BoJ to keep currency weaker?”

Goncalves believes the next iteration for Kuroda and the BoJ game plan will be looking for a transition and a narrative to exit.

“The BoJ will need to impose some constraints. It cannot keep buying at this pace, so it’s a matter of time before they need to scale back and look for ways to acknowledge that they were successful and gracefully exit,” he said.

To see the digital version of this roundtable, please click here

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email gloria.balbastro@tr.com