Global local currency bonds have been a firm favourite among emerging market sovereigns in the last 12 months. Latin America dominates a market that saw US$5bn worth of issuance last year, but the region’s supply is set to diminish as sovereigns wrestle with the twin challenges of currency appreciation and mounting inflation. Hardeep Dhillon reports.

To view the digital version of this report, please click here.

Uruguay, Peru, Brazil, Chile and Colombia are all Latin American issuers with outstanding global local currency debt. Uruguay tapped the market in 2006 and Peru in 2007, while the latter three launched transactions last year. Colombia sold US$1.3bn of 11-year debt denominated in Colombian pesos in April. Chile issued US$520m of 10-year bonds denominated in Chilean pesos in July. Brazil sold R1bn (US$597m) of 2028 bonds in October, the country’s first offering of local currency debt in international markets since 2007.

Supply of global local currency bonds this year could struggle to match 2010 volumes. Brazil and Colombia are likely to continue issuing, said Nick Chamie, head of emerging markets research at RBC Capital Markets. But Chile and Peru are not in dire need of financing means and are unlikely to tap the global markets, while Argentina and Venezuela are also unlikely candidates.

Mexico is in the unique position of having Euroclear-able domestic bonds that can be purchased by foreign investors, negating the need for the sovereign to access the global local currency markets. Peru also allows foreigners full access to its local debt markets.

“It is up to the Ministry of Finance to decide how they refinance their debt and they will determine how much Global local currency bonds will be issued upon the demand of the investor community,” said Frank Ehrich, fixed income portfolio manager of emerging markets debt at Union Investment.

Small but growing

Volumes of global local currency bonds are unlikely to rival the size of the US dollar-denominated external debt market any time soon and local government debt curves will still be a primary source of funding for sovereigns. However, the global local currency bond market is a very important development, and is likely to be a fast-growing source of funding for countries in the region, predicted Chamie.

“It is extremely difficult for investors to get access to local government debt given the fact that all currencies, bar the Mexican peso, are non-deliverable. Investors would have to open up local custody accounts in order to invest in domestic bonds,” said Chamie. “Issuing in the global markets provides easier access for international investors and the scarcity value of the bonds means that governments are able to issue at lower yields than they would typically in their local debt markets.”

Chile, for instance, shaved 20bps off its domestic funding cost with its July global bond issuing at 5.5% compared to 5.7% for local five-year debt. Brazil launched its global real transaction 350bp tighter than its domestic local debt curve.

The global local currency bond market is most liquid where there is restricted access to onshore debt. Colombia has a very high withholding tax which restricts onshore investment because the tax-adjusted yield is so low. “These taxes actually restrict onshore access and promote the global market as a liquid viable alternative,” said Siobhan Morden, head of Latin America research and strategy at RBS Securities. “Whether this global market exists or not depends on the accessibility to onshore markets.”

The huge onshore/offshore differential in Brazilian debt prompted the majority of investors to open local custodian agents onshore, lured by the opportunity to pick up incremental yield of up to 300bp from domestic bonds. Though this resulted in a rapid decline in the offshore market, that migration onshore has been restricted because of the subsequent success of the IOF tax hike to 6% on bond investments in October last year.

“That market segmentation and restricted access onshore is the catalyst for the re-opening of the offshore market and Brazil is unique, as it is forcing liquidity into its offshore bonds because of tax risk,” said Morden. “However, the majority of issuers in Latin America are refraining from external issuance because they do not want to add to currency strength. So I would not expect much more frequent issuance in this market, with Brazil the exception.”

Currency appreciation is a growing concern for Latin American countries as the region becomes ever-less competitive. “As countries try to curb the strength of their currency they will prefer local debt issuance to external, even though it can be at a higher cost for the sovereign,” said Alejandro Cuadrado, chief Latin America economist within Societe Generale’s corporate and investment banking business.

Currency intervention from central banks is creating volatility in Chile, Colombia and elsewhere, because of the potential for implementing additional measures to curb FX strength. Brazil has kept its currency at a tight range of 1.65 to 1.70 real to the dollar, which has reduced volatility, the market becoming accustomed to protective measures already in place, added Cuadrado.

According to one head of Latin America fixed-income research at a consultancy, Latin American governments are not under enormous pressure to issue bonds, but are currently experiencing a number of constraints. Investors are less enthusiastic about exploiting the yields on offer there because they expect further intervention measures, given the steep appreciation of their currencies. Meanwhile, yields tend to rise and local markets should erode in price terms as US Treasury yields increase.

“At this point in time, Latin American sovereigns would prefer issuing in the local market as they are tying to stabilise the outlook for rates. Even then, we are going to have very sporadic issuance but not large constant supply,” he said.

The outlook for global local currency bonds really depends on the outlook of the risk-free rate – US Treasuries – added Morden at RBS. The attraction for investors is that the bonds with the highest carry could help immunise against Treasury risk. However, investing in global bonds is not the same trade it was in 2010 that delivered FX gains and curve flattening in the region on the back of Treasury strength, she said.

Further FX gains are unlikely, she added, due to governments’ intervention on their exchange rates to prevent currency strength. Domestic curves are steepening because of higher Treasury risk. “Investors are almost forced into the higher yielding bonds because they need more carry to offset the Treasury risk,” said Morden. “But it is not the clear directional gains that we had in 2010. It is less compelling and has reverted into a carry trade.”

Changing faces

The investor universe has also changed. Some of the hot money flows have declined, after investors cashed in on the rapid returns from the bonds and currency appreciation, said the head of Latin America fixed-income research. “We are seeing more of buy and hold scenario rather than a buy, appreciate, take profits and get out scenario,” he said.

Pension funds, endowments and insurance companies have very large funding needs and require yields of around 6% to 8% in order to fund their future liabilities. Local currency emerging markets will therefore probably continue to be a favourite for this investor base, predicted RBC’s Chamie, as yields remain attractive.

“Yields in general are attractive as long as real yields remain positive,” added Ehrich at Union Investment. “Yields of global local bonds should be priced close to outstanding domestic issues that are normally held by local institutions.”

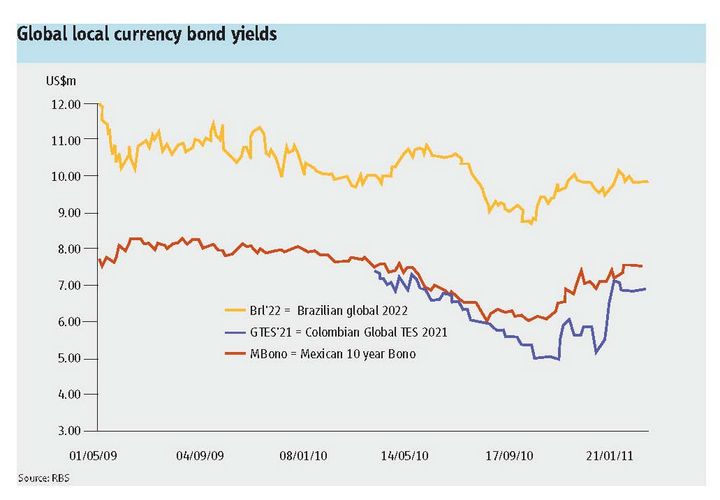

There can be a relatively wide differential between the yields on internal and external bonds, added Chamie. By mid-February, the Colombian local peso 11% 2020 was yielding 8%, a 100bp differential over the offshore 7.75% 2021 global peso that was yielding 7%. Brazil’s 2022 global yielded 9.84% compared to the local 2021 NTNFs yielding 12.34%, a 250bp disparity.

Yields remain appealing for investors, said the head of Latin America fixed-income research, with nominal yields across Brazil’s domestic NTNF curve at 12.8% from the 2000 to the 2017 maturity, declining to 12.65% at the 2021 tenor. “All that is still attractive even when you factor in the 6% of financial transaction tax,” he added.

Investing in local versus international bonds comes down to a relative value decision. The domestic market can provide better returns on a risk adjusted basis compared to global bonds, said Christian Gaier, fund manager of the Espa Bond Local Emerging fund at Erste Sparinvest. “I prefer the domestic local currency debt market as it is more liquid, has greater volumes and is traded more regularly than the international issues,” he said.

Jerome Booth, head of research at Ashmore Investment Management, sees vast opportunities for alpha generation in the Latin American region. The region is host to a range of different curve dynamics, credit cycles and economies, all having to cope with inflation. Returns are still strong and he views local currency sovereign debt as a great play on currency appreciation and the global rebalancing of the world economy.

More importantly, in the worst global scenario of an unsuccessful sovereign restructuring in the eurozone, combined with another banking crisis and depression in the US, Booth believes the safest place for investors will be in cash or local sovereign bonds from the surplus countries. Only countries with adequate reserves will be able to protect their currencies in such scenarios. At present it is the emerging market economies that hold the vast bulk of reserves and are the net creditors.

If emerging markets start selling US dollars, that currency could collapse against their currencies, driven by the behaviour of the Latin American, Asian and Arab central banks, said Booth. “From a fundamental asset allocation point of view, domestic local currency debt, even more so than the global blonds, is the safest place to invest because it is from the surplus countries and the risk of a default in Latin America is lower than some of Western Europe,” he said.