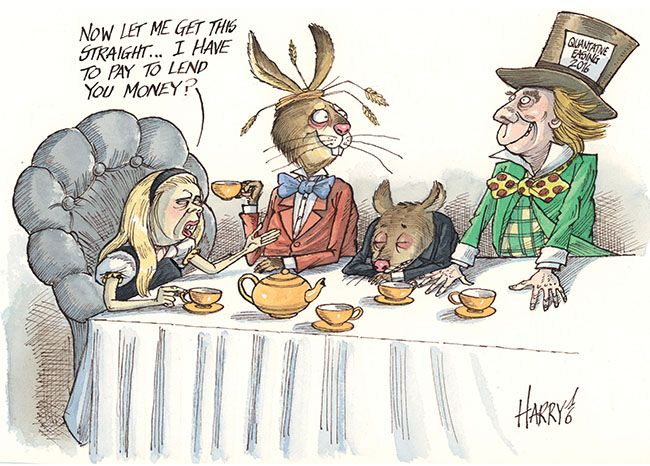

Rock-bottom interest rates, quantitative easing and negative yields have turned the fixed-income investor universe upside down. How do fund managers make sense of these changes and how are they positioning their portfolios in response?

Bunds were hardly a screaming buy at the beginning of 2016. Far from it: shorter-dated paper offered investors next to no yield at all; and even at the longer end, a 0.1% coupon on 30-year debt must have seemed like scant compensation for all the risks that might befall the investment during that time.

But applying that logic might have cost you your job: Bunds were one of the best-performing assets in 2016. If you’d started the year buying German government debt maturing in 2046, by the end of July you’d have been sitting on a paper gain of more than 30%. Even after the third-quarter sell-off you’d be looking at a juicy return of over 20%.

The performance of Bunds illustrates just how tricky bond markets have become to navigate. A decade of ultra-low rates and trillions of dollars of quantitative easing from central banks have made investment strategy more difficult than ever. Logic has been turned on its head: just when you thought yields couldn’t go any lower, they drop even further.

“Developed market government bonds have been one of the best performing asset classes in 2016, confounding many predictions at the start of the year,” said Anthony Doyle, head of fixed income business management at M&G Investments. “Year after year investors predict that bond yields will rise and year after year bond yields make new lows.”

Negative yields

Indeed, yields have come down so far that some are now negative. Four years ago, just a handful of bonds had a yield below zero, but the scramble for yield – compounded by the adoption of negative deposit rates and the expansion of QE – have driven up prices and pushed down yields. Over US$10trn of bonds now trade with a negative yield.

Negative yields turn the logic of fixed-income investing on its head: fund managers are in effect paying more for the bonds than they expect to get back. But many investors took the view at the start of the year that yields would go even further into negative territory. With that conviction, it made sense to buy bonds on the basis that yields would fall further and prices would rise in response.

“Part of the logic of holding bonds is because you need to match benchmarks and even though effectively you can have positive yield by not holding these bonds, what managers are worried about is yields becoming more negative – and missing out on the capital gains that will result from that,” said Owen Murfin, co-lead manager for global bond strategies at BlackRock. “If you aren’t holding these negative-yielding bonds, you are running a lot of risk in diverging from your benchmark.”

Fund managers also have little option but to buy these negative-yielding securities. If your portfolio is European government bonds, you simply have to hold Bunds – irrespective of where they might be trading. To find bonds that have a positive yield, some managers might need a complete change of mandate. And even those with more freedom might not be comfortable buying unfamiliar and potentially risky credits.

“There is a psychological barrier for many investors at 0%, but once you pass through that where do you draw the line? How negative you are willing to go is a difficult question,” said Steve Yeats, EMEA head of the beta fixed-income team at State Street Global Advisors. “If you decide you want to remain in positive-yield territory, then that may necessitate going a long way down the yield curve and taking some very uncomfortable risks.”

Comfort zone

Nonetheless, many managers have responded to the drop in yields by doing exactly that: moving outside their comfort zone, either by moving further along the maturity curve to longer-dated paper with bigger coupons; or by moving into riskier credits that also offer extra return. Sovereign investors might move away from eurozone debt and buy paper from Central Europe; corporate investors might buy lower-rated debt.

Issuers have responded by selling more debt. A record US$3trn of investment-grade debt was issued in the first 10 months of the year, already more than was printed during the whole of 2015. QE and the resulting hunt for yield have driven a big uptick in supply. For fund managers struggling to find palatable returns in their traditional asset classes, it has been good news: alternative sources of yield have grown dramatically.

According to David Blake, director of global fixed income at Northern Trust, the demand for yield and resulting flood of supply proves that QE is working. “Central banks clearly want you to take the next step up in risk; the search for yield that we have seen is a deliberate by-product of monetary policy,” he said. “You could argue that that policy has worked extremely well – although it has of course made the job of fund managers more difficult. You have to work much harder to add value.”

But shifts in investment trends have caused problems. Many fund managers have found themselves scrambling to update their models to understand the new range of credits and new issuers they are investing their money in. At the same time, many believe that unfamiliarity with new asset classes has sown volatility: at the first sign of trouble, new investors have a higher propensity to dump bonds rather than ride through the bump.

“People are increasingly moving into asset classes they are less familiar with,” said Murfin. “There can be bouts of volatility in these sectors – as we saw in US high-yield about a year ago – as investors get nervous and suddenly pull away. The reach for yield has led to more volatility as asset allocation can quickly change.”

Sell-off

That volatility did pick up further in the second half of 2016, when many fixed-income investments sold off. The driver? A change in inflation expectations, driven in part by rising commodity prices, and signals that central banks might be nearing their limits – at least with regards to QE. If those things bear out, bond prices should in theory track further downwards – as they have done in the second half.

So does that leave fund managers panicked? Some, at least, believe the recent sell-off might prove temporary.

“Basically the market was priced for perfection and expecting further QE, and with that as a starting point it doesn’t take a huge change in perception to move the market, and obviously we have seen a significant move,” said Yeats. “There is a gradual realisation that, although QE will still be an important driver, some of the mechanisms are starting to look a bit exhausted … But we don’t see this ‘lower-for-longer’ ending any time soon.”

At the same time, investors believe that any return to normality will be gradual. Central banks are fearful of upsetting markets too much at a time of continued economic fragility – as shown by the US Federal Reserve, which spent most of 2016 pushing back a rate rise despite growing momentum in the economy and inflation expectations.

“2013 was the last time there was a big sell-off in bonds – caused by (former chairman of the US Federal Reserve Ben) Bernanke’s comments on tapering – and we haven’t seen any central bank being hawkish since,” said Murfin. “That has really reduced concern about potential negative returns from bonds. The one big risk to that would be a rise in globalised inflation, which allows central banks to withdraw liquidity. That could mean some very poor performances for bonds.”

To see the digital version of this review, please click here.

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this review, please email gloria.balbastro@tr.com