Thirteen months ago, on the day Deutsche Bank launched an €8bn rights issue to fill yet another hole in its balance sheet - its fifth capital raise since the global financial crisis - the German bank promised investors a new era of transparency.

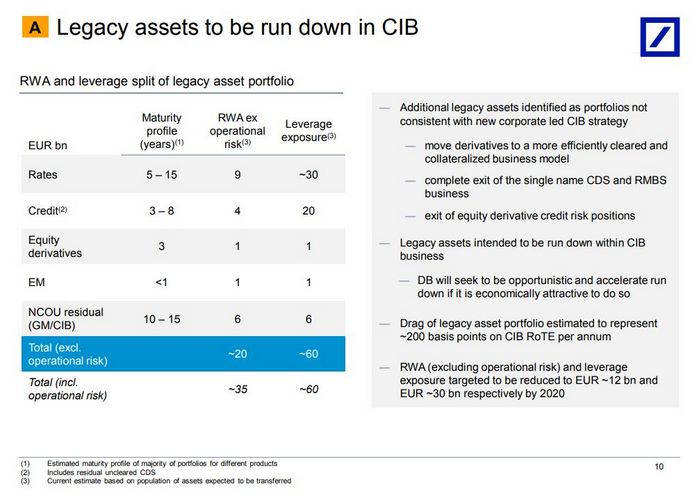

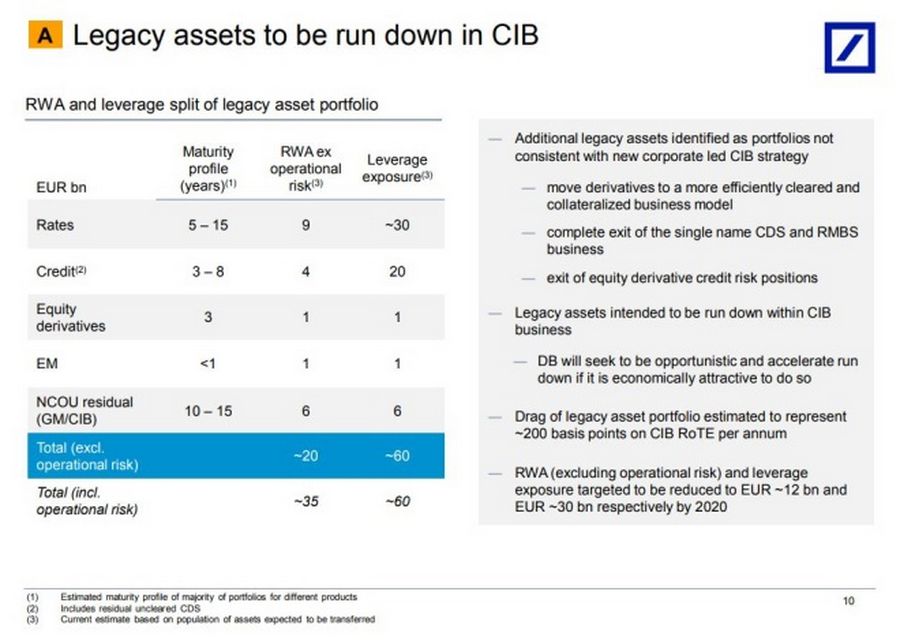

In keeping with that new openness, then chief executive John Cryan came clean about a €60bn portfolio of years-old trades that were costing the German lender about €500m a year.

Never previously disclosed, the revelation surprised analysts. Deutsche had done several clean-ups since the crisis – including one by Cryan just 17 months earlier – but had never mentioned the trades, some of which were over a decade old.

Although a relatively small piece of its balance sheet, which at the time stood at €1.6trn, the positions were consuming between €4bn and €5bn of equity – equivalent to 10% of the bank’s entire core equity Tier 1 capital base, and more than half the amount shareholders were being asked to cough up.

Worse still, Cryan said some of the positions wouldn’t run off until after 2030, more than two decades after some were initially booked.

Christian Sewing, who was running Deutsche’s private and commercial bank and oversaw the failed efforts to spin off its Postbank subsidiary, said at the time: “We just want to create the transparency that these are things we are going to work out.”

Cryan is now gone, replaced by Sewing as CEO. But the transparency that both promised to investors just over a year ago is yet to materialise. After raising the €8bn it needed, the bank hasn’t updated investors on the portfolio, other than to say late last year that it “continues to roll-off as planned”. The bank declined to comment for this article.

The legacy derivatives book isn’t the most pressing concern for new CEO Sewing, given the bank’s low returns and pressure to overhaul its strategy, but the silence surrounding the €60bn portfolio epitomises the bank’s struggle to regain the trust of investors after many years trying to fix its problems.

“It baffles me,” said one analyst who has been covering the bank for many years. “They promised more disclosure and then promptly shut up about it. You would think that they’d call it out every quarter, that they’d give you detail about what was going on. Then again, if it was just a smokescreen to basically flog €8bn of equity, then you would imagine you’d never hear of it again. I think you can draw your own conclusions.”

SCANT DETAILS

Even when the positions were first disclosed, details were scant. Deutsche said about half the trades were legacy rates positions that Cryan described as “very long-dated … old-style” positions, largely derivatives. A further €20bn were identified as credit positions.

Some €6bn were assets previously placed into a €122bn “bad bank”, set up in 2012, that presumably had proved impossible to sell or run down before the unit was closed at the end of 2016. Curiously, none of the remaining €54bn had been put into the bad bank that was supposedly designed to cleanse the bank’s balance sheet so it could move on.

Source: Deutsche Bank

One former board member who spent many years at Deutsche told IFR that the bank – despite numerous supposed clean-ups – was still carrying a large amount of trades generated before the crisis that had long ago ceased to generate returns. In many cases, supposed profits had been booked upfront – and bonuses paid – only for the trades to turn loss-making at a later date.

Stricter global regulations on derivatives and other assets brought in after the financial crisis left banks having to hold far more capital against trades. Increased funding and capital costs for Deutsche and other banks also meant that running costs for such trades are now massively higher, often turning apparent profits into losses.

“All the P&L was taken upfront and bonuses paid on it,” said the former board member. “We had a lot of dead balance sheet that wasn’t providing any P&L any longer because of this rule that you could take all the profit upfront. The traders were always interested in these trades because when you took the profit you took the bonus as well. But the bank was generally stuck with these positions.”

One senior banker at a rival firm said all big banks have some long-dated derivatives on their books, and many are painful to hold - legacy interest rate and currency swaps struck years ago with sovereigns, infrastructure companies and to enable real estate deals, for example. But some banks have managed their risk exposure or hedged positions better than others, he said. It is also clear that Deutsche was more aggressive than most in taking on such positions.

Eric Ben-Artzi, a Deutsche employee turned whistleblower, said during his time at the bank risk officers were placed under considerable pressure. “There was a lot of what was euphemistically called ‘politics’ around booking reserves or applying certain valuations or models that might result in losses,” he said.

Indeed, in 2015 the bank paid US$55m to the US Securities and Exchange Commission to settle a case brought against it alleging that it understated the gap risk on a US$98bn set of leveraged super senior trades, which had the effect of reducing its capital requirements - so possibly avoiding a bailout, say some. Ben-Artzi was a key witness for the SEC in that case.

LOSSES MOUNT

The derivatives portfolio may not result in any more writedowns. But it remains a big hurdle to efforts to improve returns. Cryan said the portfolio is a 200bp drag on the corporate and investment bank’s return on tangible equity. That equates to about €500m a year.

Deutsche said last year it wants to halve the portfolio by 2020 - with most of that reduction done by September 2018 - although it will be at least a decade before some of the more capital-intensive trades run off.

“The sooner these go, the better,” Cryan said at the time. But he ruled out paying up to facilitate the trades being sold on – as the bank did with many non-core assets previously.

Analysts have been left confused by that decision. “If you’re taking €500m-a-year pain and you’re locking up €4bn or €5bn of equity in the portfolio, why not just accelerate the run-off?” asked one. “Why were they raising €8bn of equity, when €4bn is being tied up in cruddy old books? Why didn’t you turn around to investors and say ‘we will take this loss, get rid of it’? It would have made a lot more sense.”

Management may be considering the pain Deutsche had already inflicted on investors since the crisis. Deutsche has asked shareholders to stump up more than €30bn of equity in five separate capital raises since 2008. The bad bank - or non-core unit, as it was officially known - set up to cleanse the bank’s books racked up €14bn of losses.

The decision not to cut losses on the portfolio may have been down to Deutsche’s precarious position at the time of the rights issue – not least with regard to its ability to pay coupons on certain capital-contingent bonds under German rules. Ratings may also have been an issue.

Ben-Artzi has a more simple explanation. “All the clean-ups were done by the guys that created this mess,” he said.

The question now is whether Sewing, with more capital available, might finally choose to honour his promise of transparency and draw a line under the trades.