To view the digital version, please click here.

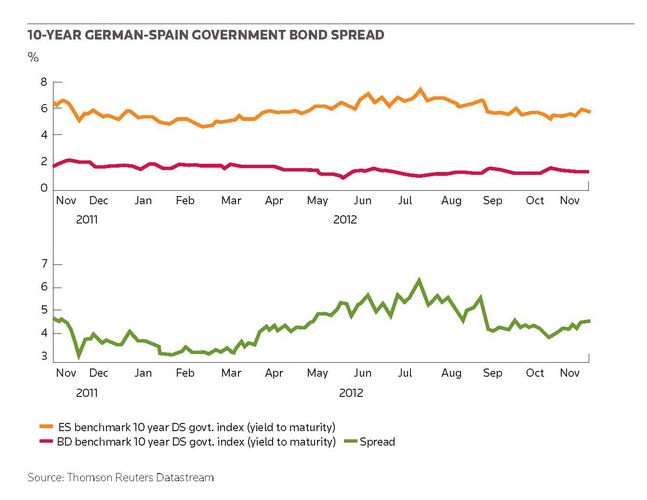

Keith Mullin, IFR: Thank you for attending IFR’s Corporate Funding Roundtable. The aim of this discussion is to review trends in German corporate funding across the bond, loan and other markets. Our discussion takes place against a very interesting backdrop both in the global economy and in financial markets. We’ve been confronted with low or decelerating economic growth, a continuing eurozone crisis, quantitative easing, bond yields at record lows, credit spreads tightening, bank deleveraging and a much more robust regulatory framework.

I’m curious to know how these issues are playing out in Germany. We’ll review what has happened year-to-date in bond and loan markets, discuss the interaction between markets in light of the technical factors at play and will focus on perspectives for next year, including for the mid-market segment. Christian can you give us an overview of where we are today in the bond market as it pertains to German corporates?

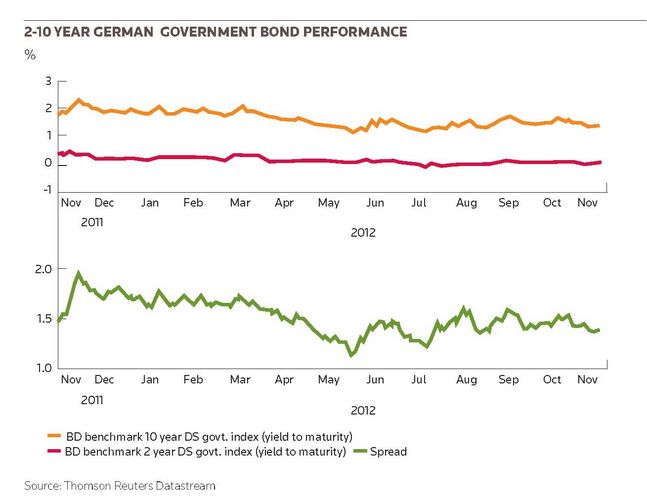

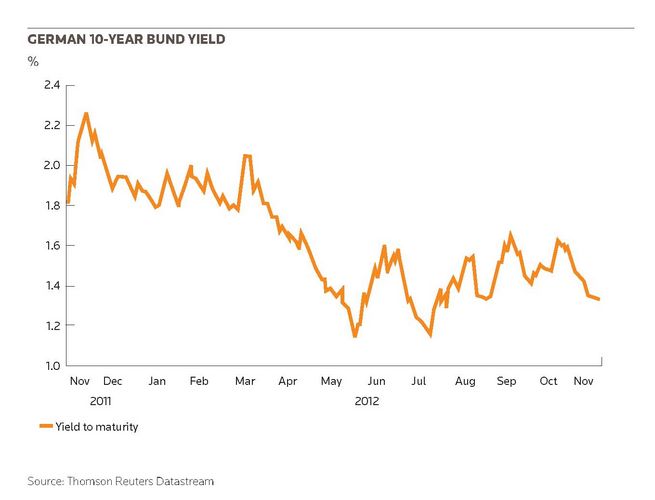

Christian Reusch, Unicredit: I think 2012 is a very good example of how lively the market has been. As you rightly said, both spreads and yields have gone down and a lot of companies have taken advantage of that. So it’s been very lively in the bond market; it’s also been a record year in Schuldscheine, where issuance has reached more than €10bn, with a lot still in the pipeline.

I think a variety of factors play into that. First of all, the overall low yield spread environment is certainly ticking the right boxes. People are saying: ’OK maybe it can go even lower but nevertheless I think it’s too cheap to be true’ so are taking advantage right now. Second, there is very healthy appetite from investors and we shouldn’t forget the macro picture. The eurozone debt crisis has also been driving a lot of activity in 2012 and that has enabled corporates to emerge [in the capital markets] in general but particularly German corporates as a sort of safe-haven asset. These factors certainly drove activity in 2012.

Keith Mullin, IFR: Claudia how would you characterise sentiment amongst corporates? Are they looking at the bond market as an alternative much more than in the past?

Claudia Hopstein, HSBC: I think you need to distinguish between the big and the smaller corporates. For the big DAX companies or issuers who have used the market often in the past, bonds have become a standard source of funding and they use the bond market whenever they have requirements. They continue to use syndicated loans as base financing, but cover additional requirements via the bond market.

I think a key development has been the broader Mittelstand segment starting to look more closely at the bond market. And not just the public bond market; a very important source in Germany is the private placement market, and we shouldn’t forget Schuldscheine, where the variety of corporates looking at that market is increasing every single day. I think that’s a trend we are going to see next year as well.

Keith Mullin, IFR: In terms of the distribution of new issues from German corporates, Marc, away from the multinationals and the well known names, are you seeing a predominantly domestic bid or are you seeing more international interest in German paper?

Marc Mueller, Deutsche Bank: The domestic bid for German names is still very strong but in addition to that German corporates in particular have been a point of attraction for a much broader investor base; European certainly, but beyond Europe as well. The German corporate asset class has been in high demand throughout the year. For the larger names, we’ve seen a lot of credit spread tightening particularly in the first half of the year.

But to the point that Claudia just made, when you look at the smaller corporates and to other financing instruments, for example Schuldscheine, which are still bought predominantly by German banks but increasingly by real-money accounts in Germany, the new development we’ve been seeing both in bonds and private placements this year has been on the maturity side. More investors have been tending towards the long end of the maturity spectrum. Even more than in past years, bonds are complementary to loans: bonds have moved towards the five to 10-year end of the maturity spectrum while loans operate in the maturity bucket below that.

Keith Mullin, IFR: Karin: one of the things that certainly worries and peeves some investors is that the strong liquidity flows into the bond market have resulted in what some see as unrealistic pricing. How do you answer that point?

Karin Arglebe, Commerzbank: That’s totally the problem. For issuers, it’s a great market because they can achieve pricing they’ve never seen before. But investors, of course, are looking for yield and the question is what they should do. One thing they can do is go for longer maturities so we are discussing with our issuers the opportunity to go not to five or seven or 10 years - the classic maturities - but maybe for even longer maturities. Utilities especially are definitely interested in ultra-long maturities.

Investors can also go down the risk curve, so not only looking at Double A or Single A rated companies. The high-yield market is more and more liquid in Germany. In the past German corporates thought of it as a junk market and would never touch it. But sentiment is better now and investors are really looking at it, even if there’s a lot of work to do with regard to documentation. Transactions in the Double B or Single B rating area could fill the gap.

Keith Mullin, IFR: So how important are ratings in this environment, because some fund mandates are quite specific. And how have unrated issuers fared?

Karin Arglebe, Commerzbank: There is still a market for unrated issuers. If you have a very well known brand name as an issuer you can tap the market without a rating. We have nice names here in Germany - Adidas, SAP and Sixt for example - that can tap the market because they’re very well known in Europe and they will achieve good pricing even if they don’t have a rating.

For other companies, we’re trying to convince them to go for a rating but for some of the German names that takes a long time. If you have a name which isn’t so good or is cross-over, the recommendation from the banks is definitely to go for a rating. When it comes to high-yield, there is no chance of issuing without one. High-yield means rating.

Keith Mullin, IFR: OK. So let’s shift to the other side of the table now. Johannes, there’s a great story in the bond market, great technicals and a good flow of issuance. How does the story play out on the syndicated loan side?

Johannes Heinloth, global head of loan syndications, BayernLB: We’re just taking a rest and allowing the bond guys to run the show and we’ll probably be back in a year or two. No, honestly, I mean volumes are down and numbers are down. The purpose of the majority of loans is still refinancing so from that perspective we’re still missing big M&A activity. Of course there have been big M&A deals this year, including SAP, Fresenius, Linde and others, but they’ve all been taken out by DCM transactions.

The syndicated loan market seems to be here for a different purpose now. One is certainty of funds when it comes to event-driven financing. Beyond that, refinancing is OK; there are still companies out there looking for attractive spreads. We’re seeing the first wave of extension options approaching the market and we can clearly see that no-one is asking for additional fees, which is a sign of how desperate people on the loan side are for deals and for staying in these transactions.

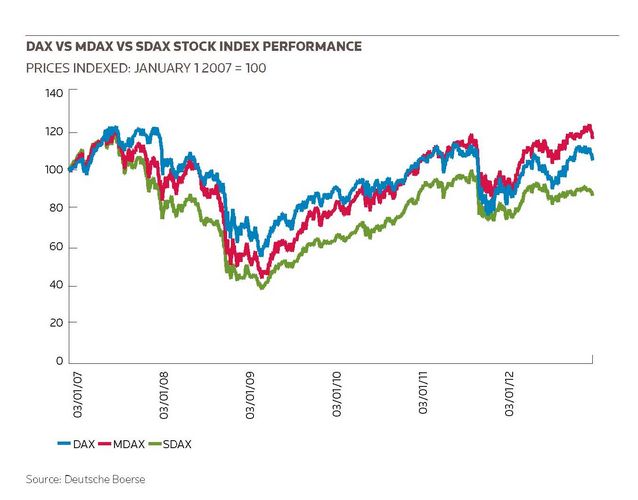

Of course, we are all keen to find new opportunities to do transactions and this is probably in the SME market rather than in the DAX or MDAX segment. And there you can really see quite interesting names with interesting activities and interesting transactions which will help us to at least come close to the initial budgets we signed off almost a year ago.

Keith Mullin, IFR: Matthias, do you have to work much harder to get transactions? What pricing issues is the current environment throwing out?

Matthias Gaab, Deutsche Bank: What we all have to take into account and are taking into account is that the market has changed. As opposed to what we discussed at this roundtable a couple of years ago when the issue was loans in competition with bonds, these days it’s a more complementary product. In terms of why loans are used from a lender’s perspective - at least certainly in the DAX and MDAX space - the purpose has changed over the last couple of years.

Loans constitute base financing in the sense that they provide flexibility that capital market products don’t and can’t, so a certain volume will continue to be established by respective borrowers over time. Actual funding needs will continue to be raised in the bond market because it’s more attractive especially given what was just mentioned with respect to the investor base.

On the other hand, refinancing costs for the banks don’t make funded lending too attractive for the time being. That’s a fact of life. That said, as we have seen and as Johannes mentioned, lending and loans will continue to be available. Everybody is interested in being a facilitator of event-driven transactions but in the first instance there needs to be two parties that want the event to happen so we are dependent on sentiment with respect to M&A transactions.

Keith Mullin, IFR: Reinhard, most of the issues around Basel III are well known but what impact is it having on a day-to-day basis not just in terms of how you originate loan transactions, but in terms of any additional internal hurdles you have to hit to get approvals?

Reinhard Haas, Commerzbank: Basle III is being discussed at all of the banks. As of today, it’s still being worked on; there are a lot of issues around it and there’s no simple decision process. It’s not a question of rules that have been sketched out and which are being finalised; it’s a process and there’s still ongoing discussion on the treatment, for example, of undrawn lines. And remember that 2018 may well be the official implementation date but it won’t be like a guillotine falling; it’s an iterative process that will be revised a few times before it comes into force.

But clearly it’s something we’re all considering. I think it is behind the change in behaviour of the capital markets, with funded debt morphing from loans to bonds and other fixed-income products. That’s a healthy movement. I think we’ve all been encouraging that, as banks, and we see that being realised with the large caps and the larger mid-caps. Obviously it hasn’t reached the SMEs yet: everyone talks about the ebullient Schuldschein market but that can’t really be the answer because in the end they are bank credits.

What we would expect over the next few years is the development of a European market below the corporate bond threshold; let’s say something similar to the US private placement market. But you would have to have a uniform format for that issuance which we don’t have at this point in time. Many European markets have local forms of private placements; the Schuldschein is the German version of it. There is a different one in Switzerland, a different one in Austria and a different one in the Scandinavian countries.

We need to have a deeper market for that kind of issuance but there needs to be an agreement on a supranational basis, which we don’t have in place yet. Within all of our institutions, there are ongoing discussions with investors, mainly insurance companies and pension funds, but it’s evolving, I would say.

Keith Mullin, IFR: The Mittelstand seems to be a potential battleground in terms of where funding is going to get done. Will those battle lines be drawn around funded versus unfunded or will there be other kinds of issues at play? Where is that battle going in terms of where Mittelstand companies are going to find funding at optimal cost?

Johannes Hack, DZ Bank: I’m not sure it’s going to be an issue so much around funded versus unfunded. I think the issue is probably going to be more one of tick-the-box Mittelstand versus more complex credit stories because basically with the reasonably well known Mittelstand companies that have good markets, good prospects, good reporting and which tick the banks’ boxes in terms of rating, they can pick and choose whatever instrument they want and will be able to do so for the foreseeable future. Banks are keen to lend, bond investors are keen to lend; Schuldschein is that hotspot, that island of serenity in troubled waters so they’re not fussed, they don’t need to worry.

But there’s another segment of Mittelstand companies which adhere more to the traditional view of what Mittelstand used to be, perhaps a company where financial reporting isn’t all it’s supposed to be, where accounts are late in coming; those types of companies I think are the ones, certainly for us, that will be interesting to work with, where we can go in and provide broader financing while maintaining an adequate credit profile.

Keith Mullin, IFR: That’s an interesting point. If I can come back to you guys on the bond side, banks exist effectively to lend - in theory anyway …

Christian Reusch, Unicredit: Even in practice. It would be wishful thinking even for a DCM person to say: ’OK: we’ll just hop on, facilitate and create a big bonanza’. That would be too naïve an approach. I agree that bonds and loans are complementary. Sometimes there are phases where the bond market or the Schuldschein market are viable alternatives in terms of available size. But this can turn quickly. So from that perspective, it’s not about the good, the bad or the ugly. The two products are complementary, like yin and yang.

Keith Mullin, IFR: Claudia, one of the things banks are set up to do is to carry out the credit work required to make lending commitments whereas bond investors are typically not quite so credit intensive. I know this is a generalisation or am I misrepresenting bond investors here?

Claudia Hopstein, HSBC: I think investors do it differently to lending banks, but all the big investors, as well as second and third-tier investors have their credit teams, do ongoing credit research, have standard lines in place at least for the more frequent names and can very quickly take on board new names. Whenever there’s a roadshow, the room - regardless of where you go in Europe - is crowded and quite often there aren’t enough chairs.

I think investors do it differently to lending banks, but all the big investors and second and third-tier investors have their credit teams, do ongoing credit research, have standard lines in place at least for the more frequent names and can very quickly take on board new names. Whenever there’s a roadshow, the room - regardless of where you go in Europe - is crowded and quite often there aren’t enough chairs.

So bond investors do carry out credit work, but do it differently. They’re used to making quick decisions and they do ongoing analysis. As soon as they have one of their names in the portfolio they look at it on a permanent basis. The bank looks at it from a different perspective; it has a longer relationship approach.

Reinhard Haas, Commerzbank: What you have to see is the difference in what investors are looking for. A bank will always look for a long-term relationship, at least in most of the corporate world, and will lend into very diverse situations whereas the bond investor is more interested in having money at work earning a coupon so it’s more for standard situations where it is appropriate. It’s not that the analysis is any different. But as well as the standard situations, we in the loan market deal with the more sophisticated stuff as well; the more problematic situations. And obviously we can do the whole credit spectrum, which is not the case on the bond side because that’s not what investors on the bond side are seeking. It’s a different animal.

Claudia Hopstein, HSBC: But we have the high-yield segment.

Reinhard Haas, Commerzbank: But again that’s also for longer-term investment. It’s not for short-term situations, it’s not for special situations and it’s not for small companies. It needs a rating with permanent credit surveillance. We have all that within banks.

Keith Mullin, IFR: But if I can come back to you Claudia you said that bond investors do the credit work. My follow up question would be: away from the frequent borrowers when you’re looking at perhaps more infrequent borrowers or debut borrowers, would bond investors look for more return than lenders because lenders are looking for other factors, like relationship?

Claudia Hopstein, HSBC: Leaving aside the issue that has already been mentioned about different maturities, if you look at the bond market, you have benchmark issues where you have liquidity behind it and investors get some comfort from that. And yes, they do require a premium for sub-benchmark deals which would in most cases be what smaller entities are looking for. They would also require a premium for unrated names. On the bond side, you don’t have the relationship approach and you don’t look at the entire relationship that a bank has with corporates.

I think - and I hope my loan colleagues agree - that a bank looks at a lending relationship from a different perspective. They go for the whole picture. Most banks are not interested in lending only: they want to do ancillary business whatever that may be; cash management, payments, export finance etc. They are after additional income streams. A bond investor is a bond investor. That’s the only relationship they want with corporates.

Matthias Gaab, Deutsche Bank: I think it’s probably also vice versa in that from the borrower perspective, they’re seeking a different kind of relationship. A borrower expects a specific kind of relationship from the bank, i.e. providing credit lines, getting other services, especially not selling out of the loan after, say, 12 months or whenever we feel less happy about the quality of the credit or the performance of the client whereas an issuer probably looks just quote unquote ’for the money’ from investors. It’s probably a different ball game for frequent issuers, but broadly speaking it’s probably the money beyond anything else.

Reinhard Haas, Commerzbank: And most of the time it’s complementary because the banks do the unfunded piece and we’re very happy for the bond market to absorb the largest portion of funded debt, which especially for the large caps, banks would over time probably not be in a position to provide in the same way the bond market can.

Johannes Heinloth, BayernLB: When you live in a borrower’s market like we do right now and you want to be awarded the next bond mandate, you need to make concessions on the loan side. That’s the game. But your question about return expectations between the bond and loan markets implied that banks are less return-driven than bond investors. That’s definitely not the case.

Marc Mueller, Deutsche Bank: Let me bring this complementary element in again. The combination of the loan and the bond in the capital structure of the client offers diversification value in corporate funding strategies. But given the house bank principle that many German corporates have, the bank is a very important partner for most German corporates and will remain so. The capital markets offer a cheaper funding source for different maturities, for different currencies and other aspects, so that brings diversification and stability to the capital structure. But it’s about partnering up with a house bank for the long term together with diversification to be gained from the capital markets.

Karin Arglebe, Commerzbank: I think that’s very important. Only last week I had a client saying that they would like to convert all their bank loans into bonds because it’s so cheap and so flexible. You have to have your core banks, your house banking system in Germany, you have to have your lines, your working capital etc. The basic financing can go out to the capital market but you can’t survive without having a handful of core banks.

Johannes Hack, DZ Bank: I would make the point, going back to what Johannes was saying, that loan bankers, too, are supposed to make money. There’s something slightly weird about this discussion because theoretically we are all pricing borrower risk so we should all be coming to the same conclusion on pricing because that’s what the credit risk is of the borrower.

And if that doesn’t happen, and if that doesn’t happen on an ongoing basis, it either means that we as banks are such lousy risks that people don’t want to lend money to us (which potentially may be an issue these days) or it means that we’re allowing ourselves be drawn into this ’we’re at our client’s side through thick and thin’ issue. Yes we are, but that doesn’t mean we’re not in the business of making money.

And clearly one of the things we need to get across to our clients over time and to the extent that market conditions permit, is that the loan product too is one that needs to pay for itself. It’s not something you give away in the hope that something else will come along because that’s not going to work, not for everyone in the long term.

Keith Mullin, IFR: So does that infer that the relationship banking model has evolved over the last let’s say two to three years to the point where you need to factor in that you need to make money and your costs are going up so you pass those costs on to your borrowers?

Johannes Hack, DZ Bank: Well I think the honest answer to that is I’m not entirely sure. Clearly in the climate we are in, it is beneficial for banks to be seen to be returning to the roots of what their business is, i.e. lending money to corporate clients rather than doing other silly things. And within that general context I guess there’s also a general move back to maintaining things that tended to make banking a good idea, for instance the house bank model.

And if you take that to mean that we now need to be seen to be doing things for our corporate clients then potentially I guess you can get into a situation where you’re led not only by yield considerations but also by considerations of being seen to be doing sensible things against an extremely benign economic backdrop as far as our clients are concerned.

I guess for me the interesting thing is going to be when the economy starts slipping and our borrowers start slipping. Is that going to alter the pricing situation or are we then still going to say: ’well we’re house banks and we need to be with you through thick and thin’? We will know that I would guess some time next year or the year after.

Johannes Heinloth, BayernLB: There is one trend in the syndicated loan market and that is for borrowers to rebuild their banking consortia, if that’s the right way of putting it, and reduce the formerly high number of banks they want to work with. So you see the number of banks as core banks being cut - and by the way I prefer the term core banks rather than house bank because house bank sounds like there is a bunch of stupid guys out there who are not able to do proper calculations on their invested capital.

And that means the role of being a core bank is becoming more important than in the past. For me, the question you asked earlier about pricing should be: are banks now putting more emphasis on getting loan pricing right? And the answer here is clearly because the shortfall is rapidly increasing as we move towards the 2019 implementation date for Basel III and secondly that with so-called ancillary products you make less money. Bonds are a standard product these days and flow products are less attractive, speaking in very broad terms. So to bring these two ends together you need to somehow adjust either side of this equation and from our perspective it’s probably a re-pricing of the loans.

Keith Mullin, IFR: Matthias, is the pricing issue also perhaps about a more realistic expectation around ancillary business? The notion we’ve lived with for the last couple of decades is that banks will lend in the hope they might pick up ancillary business, whereas these days there’s a lot more emphasis on calculating the return on that relationship and the value of any ancillary business you are getting. Are you as a bank more aggressive, let’s put it that way, around making sure you do get ancillary business? And if you’re not getting it, does that mean you necessarily re-evaluate the relationship you have with that client?

Matthias Gaab, Deutsche Bank: Well I think what we have experienced over the last couple of years is that that discussion has certainly intensified between the client and the bank with respect to what the cost of lending is and what other revenues a bank can achieve through ancillary business. And what we have also seen over the last two years in the German market is that for various reasons some banks have withdrawn from certain client relationships.

But what’s certainly extremely good news is that clients acknowledge that banks need a certain amount of ancillary business, which brings us to the conundrum of whether they are prepared to stand by their word and provide that ancillary business to their lenders.

On the other hand in order to make that ancillary business meaningful in volume terms, they are trying to reduce the group of banks they deal with which then brings in another conundrum, which is bigger lending lines. But certainly the good news is that clients are acknowledging the requirement to share the ancillary business on a negotiated basis. That’s certainly something we should bear in mind.

Keith Mullin, IFR: So would you all share that sentiment?

Reinhard Haas, Commerzbank: Yes, it’s a phenomenon which is absolutely true for the large caps and larger mid-cap companies. I think that would be a slower process in the SME segment because the German bank market, unlike some of the other European bank markets, is not yet consolidated. You still have a four digit number of savings and loans banks organised on a federal level, and several hundred mutual banks.

And as long as that exists, there’s a large amount of ’cheap’ money coming from the smallest banks which is yet to be consolidated. You can’t exercise a strong levy as a bank for cross-sell when the Mittelstand client can get cheap funding from a savings and loans bank that simply tries to manage costs in an efficient way for itself.

You can’t blame the SMEs for that but it’s a situation that we will slowly see evolving over time, coming back again to the Basel III rules. This could lead to a consolidation of the savings and loans and mutual bank market. That will impact the smaller corporate segment in Germany.

Karin Arglebe, Commerzbank: Companies have to share their wallet on the bond side, too, so we see not just two bookrunners on deals but four, five or even more. The simple issue is that companies have to share the wallet and they have to give the mandate to more banks.

Christian Reusch, Unicredit: I think an overall reduction in banking relationships will address this. I think it puts both parties into a situation that’s mutually beneficial, where you have to put more emphasis on your credit work as a bank because ultimately it means also that you might need to extend more lending since whereas before the client might have had 10 banks, it now has have six or seven and this obviously has to be put on fewer shoulders.

From that perspective, the dialogue is much better than it has been in the past. I think people do understand you need to share wallet. That’s the most important message. Service has some cost. Obviously you cannot charge the full amount on every service that you would like to charge so there’s a negotiation process going back and forth. At the end of the day your overall package must be beneficial for both parties. And as long as this works you can get along with each other for a long time.

Reinhard Haas, Commerzbank: It’s especially in a downturn in the economic cycle where it becomes more evident that liquidity has its cost. We saw that in the aftermath of the 2008 market retrenchment, which was recognised by many of our clients, who also saw the stability of the loan market aiding them in that specific situation. That’s where the core bank system really worked for those who had it.