An eleventh-hour deal between Greece and its creditors to unlock desperately needed funds for the government and narrowly avoid default will not end the acute liquidity and solvency crisis being faced by the country’s banks.

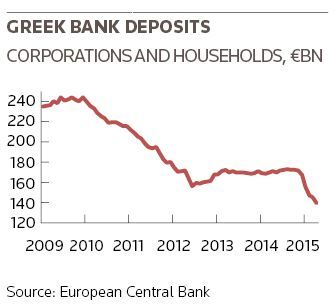

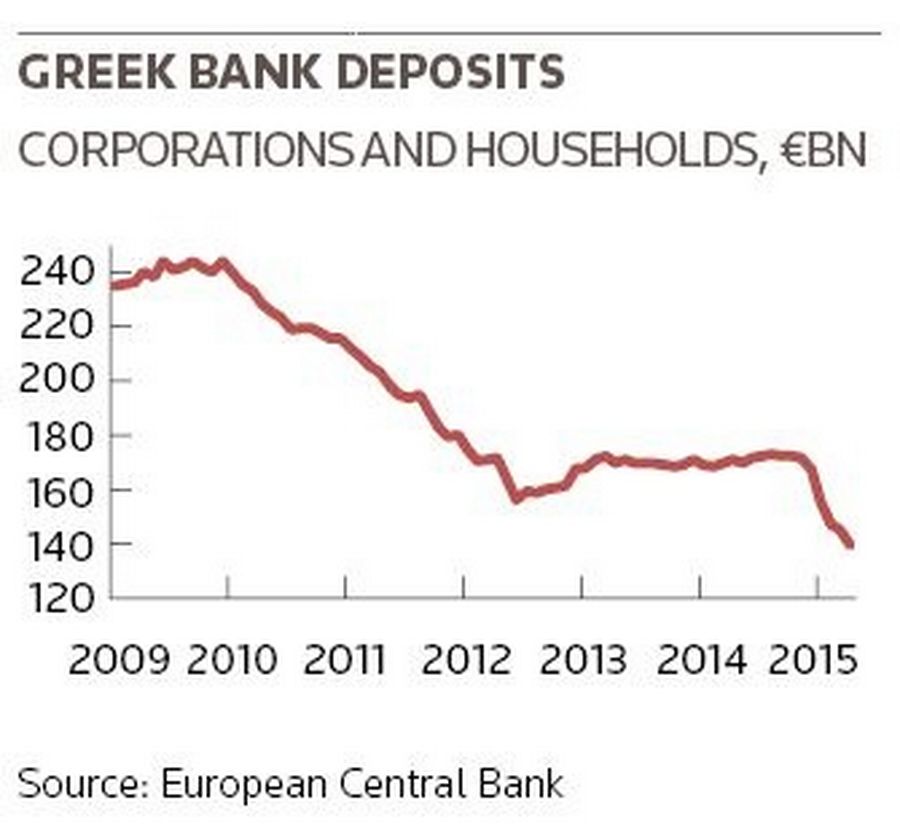

Although a deal should halt a slow run on banks that has seen them lose €44bn of deposits – a quarter – since December, additional austerity measures that Athens will probably have to agree to unlock rescue funds could inadvertently exacerbate problems for the banks.

Lenders including Alpha Bank, National Bank of Greece, Piraeus and Eurobank are already under severe strain. With 40% of bank loans classed as delinquent, about two-thirds of all bank revenues are being used to provision for expected loan defaults.

But with additional austerity measures likely to be imposed on an already struggling economy, banks may need to step up that provisioning, forcing them to slash the few funds earmarked for new lending and pushing them to find new cost-savings.

“More recessionary measures – they shouldn’t be described as reforms – are only going to exacerbate the bad-loan problem for Greek banks that are already struggling,” said Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou, a market strategist at JP Morgan.

“Greece and its creditors clearly need the banks to start lending again to break this negative cycle, but right now making new loans is the last thing on the minds of Greek banks – they have lost so many deposits, they are in crisis management.”

Slow bank run

Problems have been particularly acute since January, when the election victory of a left-leaning coalition and subsequent standoff with creditors led depositors to pull their money out of banks amid concerns about the country’s future in the euro.

Since the end of last year, banks have lost about €44bn of deposits that used to fund their operations. At the same time, they have lost tens of billions of euros worth of repo funding as large foreign investment banks have cut credit lines.

Shut out of capital markets and cut off from the European Central Bank’s normal funding operations since February, banks have for the last few months been almost completely reliant on emergency liquidity assistance from the Greek central bank.

A deal with creditors should mean Greek banks regain access to cheaper ECB funding facilities. But deposits will take time to come back. In 2012, after a similar slow bank run, it took eight months for deposits to return to previous levels.

“This money won’t stay under the mattress forever,” said Panigirtzoglou. “People will put their banknotes back into their bank accounts if they see a deal, but it will be slow, meaning the banks will remain under liquidity stress – though much less acute – for some time.”

The biggest problem, however, remains on the solvency side. Despite officially having adequate levels of capital after five years of reforms, clean-ups and capital injections, Greek banks are still largely unable to fulfil their raison d’etre – lending.

Analysts say bankers are distracted by their bad loans. The big four banks – Alpha, NBG, Piraeus and Eurobank – put aside €5.6bn in provisions last year, eating up about two-thirds of all the revenues they generated, and leaving little to pay running costs.

The need to preserve capital for current and future writedowns means resources are being sucked away from new lending. Credit has fallen on an annualised basis in every single month since July 2011; total lending has fallen by a third since 2010.

Loss making

Many analysts expect the four big banks to remain loss-making this year – even before new austerity measures are factored in. Fokion Karavias, chief executive of Eurobank, has described the firm’s strategy as “remedial management”.

“In this environment, our strategy during the first quarter of 2015 was to focus on remedial management, reduce further the cost of deposits, contain operating expenses, and improve the performance of our international operations,” he said.

What is worse, many believe that even these mammoth provisions are not enough. “While loan-loss reserves rose in 2014, they remain insufficient to cover expected losses, particularly as banks’ ability to foreclose on residential properties remains constrained,” Moody’s warned recently.

There is little banks can do. Only a year ago, all four major Greek banks were able to sell senior unsecured bonds to private investors – at reasonable levels – but those markets are now shut, partly because of the government’s liquidity crisis but also as a result of the deterioration in the wider economy and the impact on banks.

“There really isn’t much that Greek banks can do apart from cost-cutting at this stage,” said Jonas Floriani, an analyst at Keefe Bruyette & Woods, who believes that the government needs to work with the sector to find a solution to the current banking problems.

“Politicians need to implement a framework for NPLs to be addressed and taken out of the banks’ balance sheets. If banks need fresh capital, the government will need strong arguments to convince the private sector to get involved. It is unlikely the government will inject capital as there is no money around.”