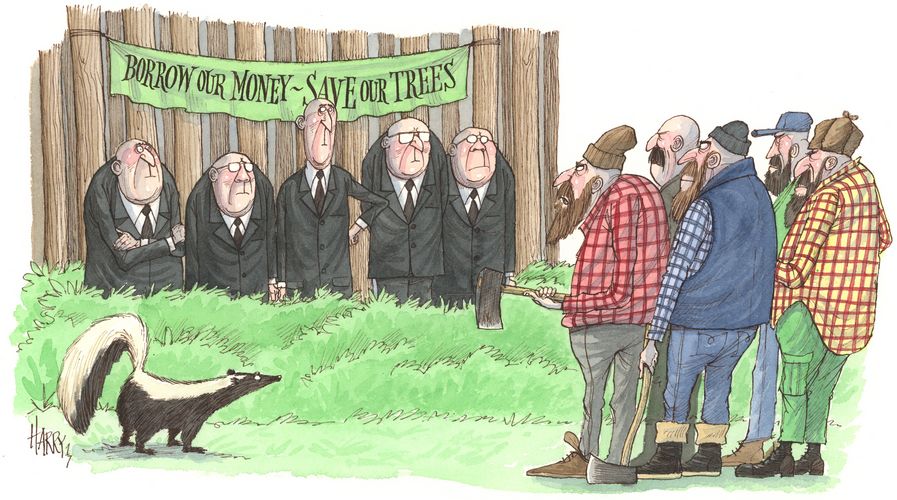

Green bonds have quickly become an important piece of sustainability financing. Yet while Green loans have emerged more slowly, they have plenty to offer both borrowers and lenders – and provide options not available in the bond market. Environmentally responsible lending may finally be ready to take off in earnest.

Green bonds have made a definite impact on financing since the first issue was launched a decade ago, and now Green loans are starting to carve out their own niche as well.

Though slower to catch on – Green bond issuance topped US$100bn in 2017, compared with less than €10bn in loans – Green loans have plenty of appeal for buyside and sellside alike.

The data providers have yet to start specifically tracking Green loans so it’s hard to be certain, but the asset class probably began in July 2014 with a £200m deal for British supermarket group J Sainsbury. It then went quiet until a sudden surge in early 2017.

Most of the first wave of Green loans came from borrowers that had already launched comparable bonds. Because they had introduced the necessary additions to their accounting and reporting systems it was a relatively simple step to use loans as an additional source of sustainable financing.

And while the earliest issues tended to have a use-of-proceeds structure similar to their bond cousins, the asset class is evolving towards a model based on covenants.

“This year we have seen the introduction of loans that are not specific to projects,” said Cecile Moitry, director in sustainable investment and finance at BNP Paribas.

“Loans are extended to the borrower for general corporate purposes but they are also linked to sustainability performance,” Moitry told IFR. “If the borrower reaches certain targets, then a bonus is triggered.”

That “bonus” comes in the form of a lower margin paid on the loan, giving borrowers plenty of incentive to stay on track with pre-defined targets.

Philips has such a structure built into its syndicated €1bn five-year revolving credit facility, for example.

It pays a margin linked to a sustainability rating provided by corporate governance research firm Sustainalytics. When the rating goes up, the margin goes down – and vice versa.

Commercial property company Unibail-Rodamco, meanwhile, refinanced a loan with a structure that links the margin to long-term credit ratings and three Green performance indicators.

“Borrowers are interested in this type of structure, as it allows them to align commitment to sustainability with the cost of financing,” said Moitry.

While the extent to which the borrower benefits or is penalised is not transparent, bankers say it is only a small deviation from the overarching link to creditworthiness.

Still, there is obviously value even in just a few basis points of cost savings.

“It’s another step forward in the development of sustainability finance,” said Moitry.

NICELY FLEXIBLE

Loans are also typically more relationship-driven than bonds, which allows borrowers more flexibility while giving lenders greater scope to push for green goals.

“A loan is more of a bilateral relationship than is found in the bond market,” said Tanguy Claquin, head of sustainable banking at Credit Agricole CIB.

“With Green loans, banks can directly incentivise a client to improve on its ESG performance. It’s more difficult to distribute non-standardised products to a large number of participants.”

This is especially important in a climate where many funds are using their cash to support banks showing dedication to ESG.

“Banks need to be making a commitment to sustainability,” said Stephanie Sfakionos, head of sustainable capital markets at BNP Paribas.

“They need to show to their shareholders that the lending they make has a positive ESG impact, and they need to be consistent with their clients by aligning strategies.”

That alignment thus far has been mainly evident in larger syndicated, club and bilateral deals, but there is potential for expanding the practice to smaller corporates.

“Green loans could be extended to help SMEs finance assets and operations with an ESG caveat, without the cost of visiting the Green bond market,” said Marie-Benedicte Beaudoin, client relations manager at Oekom Research, which specialises in rating environmental and social performance.

“The structure is certainly transferable to SMEs,” said Roland Mees, director of sustainable finance at ING Bank. “In fact, ING has already done one such deal.”

Meanwhile, loans give borrowers an option for discretion not available in the bond market, said Cedric Burford, partner at law firm Clifford Chance.

“Not everything has to be in the public domain,” he said. “A company can always go and talk to its lenders if it is not comfortable with the Green covenants it has signed up to.”

STANDARDS FOR ALL

Yet while that kind of flexibility is appreciated, plans are afoot to develop principles and create standards applicable to all Green loan transactions.

“There’s a great deal of interest in Green loans and we’re leading the group working on Green loan principles,” said Clare Dawson, chief executive of the Loan Market Association.

“With any new product, it can be helpful to establish standards,” she said.

“A lot of the elements will be the same as with the Green Bond Principles, but we’re discussing how to adapt them to reflect the attraction of the flexibility afforded by the loan market.”

Indeed, having a set of transparent principles inspires investor confidence – and has helped Green bonds develop into an important market force in just a decade.

There is also the prospect of additional economic benefits, should policymakers decide to look more favourably on sustainable risk.

The EU High-Level Expert Group on Sustainable Finance highlighted opportunities to adapt prudential rules to better reflect long-term sustainability risks.

“Green-supportive factors or brown-penalising factors could be investigated,” it said in a recent report.

Standardisation could also be the spur for non-bank investors to take a closer look at the loan market as they search for further exposure to green portfolios.

Despite the attraction of aligning interest payments to ESG, though, something similar is unlikely to catch on soon in bonds, since the borrower/investor relationship is more anonymous.

However, some believe that could happen as well.

“We could at some point see Green bonds where the coupon would be paid not only based on par value, but on par value multiplied by an indexation coefficient,” said Jean Luc Lamarque, global head of syndicate at Credit Agricole CIB.

“It would work in a very similar way to inflation-linked bonds, but in this case the coefficient would be generated by the green performance of the issuer.”

To see the digital version of this review, please click here.

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this review, please email gloria.balbastro@tr.com.