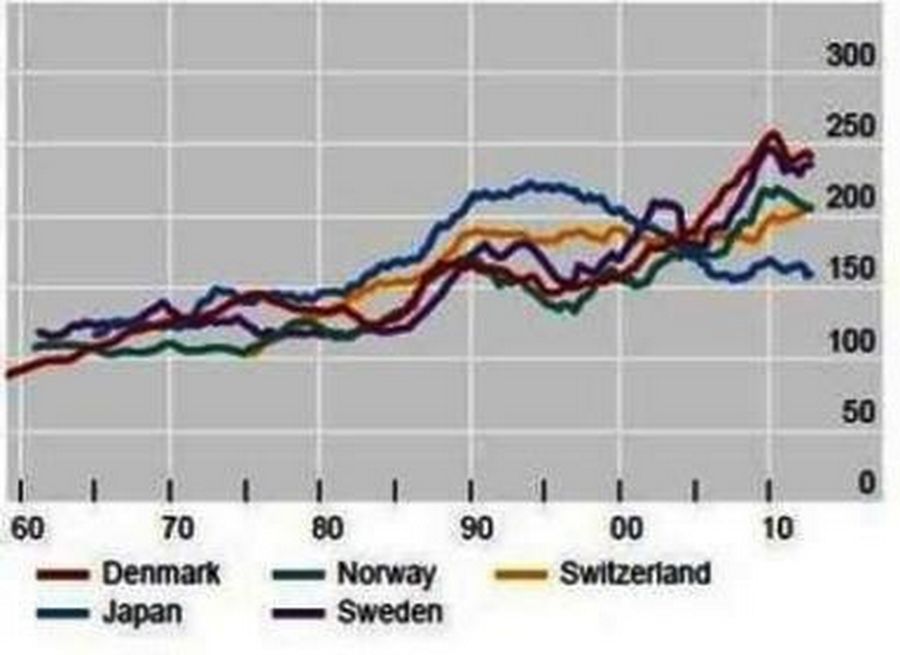

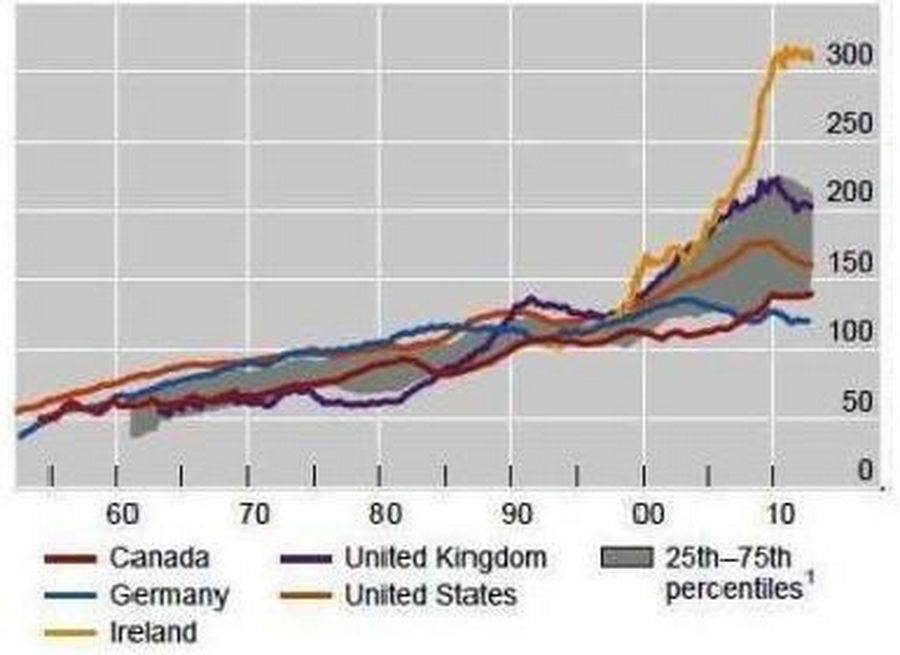

Since 2010, private sector debt levels in the US have fallen somewhat, but there has been little deleveraging elsewhere. BIS research publication presents a view of pure private sector debt growth in the world’s major economies. The graphs below show the long run growth in private sector debt to GDP ratios across several countries.

This includes households and non-financial corporate sectors. Focusing on the period 2000–10, this data set shows private sector credit has grown very substantially relative to GDP. Since 2010, private sector debt levels in the US have fallen somewhat, but there has been little deleveraging elsewhere. The chart titled “Economies with high credit-to-GDP ratios” shows Japan’s private sector debt falling from about 250% of GDP in 1995 to about 150% in 2012.

Now that the crisis has taught governments and markets the dangers of excessive leverage, we can expect a continued focus on reducing private sector debt levels. Though not shown in the graphs, China’s private sector debt to GDP has grown sharply again during 2009–12, from just above 100% to nearly 140%, and there is increasing concern that this rapid increase in leverage presages a crash.

As the Japanese experience shows, a long-term deleveraging trend in the private sector can:

♦ dampen economic growth

♦ force down corporate earnings and stock prices

♦ lead to an increase in government debt

♦ force central banks to intervene repeatedly

♦ keep bond yields and credit spreads low

As a result, in a deleveraging regime, fixed-income (and credit) returns are likely to be more attractive relative to stocks. By comparison to the US and UK, Germany has constrained private sector debt at manageable levels. We do not expect the US, UK or Germany to follow exactly in Japan’s footsteps because:

♦ their economies are more open and flexible, including in relation to employment, immigration and wages

♦ the demographic profile is very different

♦ starting (2010) debt levels are lower, and

♦ central banks are focused on not repeating Japan’s experience

However, we can still expect some aspects of the Japanese experience to apply, in particular that the struggle to reduce private sector debt leads to:

♦ slower economic growth and low inflation

♦ more bouts of government and central bank intervention to “manage” the deleveraging process, and as a result,

♦ an environment more conducive to positive credit market returns relative to stock returns, assuming central bank interventions successfully prevent outright deflation

There will be ups and downs though, partly because US Treasury, Bund and Gilt yields had fallen too far by May. Yet, if yields rise too much, economic growth is likely to slow as a result. For example, even in the current debate around tapering, the Fed has already mentioned the negative growth effect of higher mortgage rates. Goldman Sachs’ economists estimate that housing contributes 0.75% per annum to real GDP growth over the next six quarters, a very big part of their 1.5% per annum real GDP growth expected for the US economy for 2013.

To sum up, in the western world, private sector credit as a multiple of GDP is likely to contract over the next decade, triggering the need for further rounds of government and central bank intervention. If, as looks likely, a Great Depression-style deflation scenario is avoided, this environment of deleveraging, low growth and low inflation is better for fixed income than for stocks, and is especially good for financial institutions’ credit (as that sector deleverages more than others).