Rapid growth in the Green bonds market is fuelling debates about standards that ultimately ask what projects are, in fact, really “green” and what is the best way to grow them.

This year may turn out to represent something of a turning point in the arduous debates about global warming – far from being settled, it does appear at least to have arrived at the conclusion that evidence for man-made climate change is irrefutable.

Consensus may finally be in prospect in sweeping arguments that have ultimately turned on a fundamental philosophical axis: is it possible to have both economic growth and a clean environment?

It seems that we may be able to have our cake and eat it. In a flagship report released in September, the Global Commission on the Economy and Climate refuted the idea that we must choose between fighting climate change or growing the world’s economy.

This conclusion is likely to be of paramount importance to the development of the Green bonds market, where rapid growth has spawned a similar debate.

Changing attitudes

Changing attitudes towards how capital markets view the green agenda were very much in the air at last month’s UN Climate Summit in New York, where investors representing more than US$2trn under management issued a statement committing to grow a global market in Green bonds and were backed by development banks and issuers. UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon ensured that Green bonds were a key area of discussion.

The role of capital markets in battling global warming is a crucial issue because public sector funding alone stands no chance of resolving our planet’s most pressing problems.

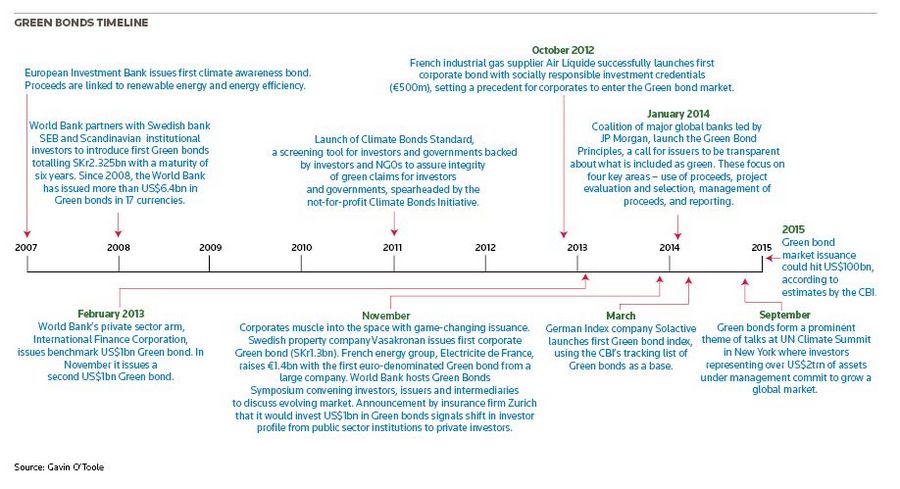

An offspring of the multilaterals, Green bonds took off in 2013, with the Climate Bonds Initiative expecting US$40bn issuance this year and US$100bn in 2015.

As both products and the issuer base have broadened, attention has moved to questions of sustainability. Standards and criteria are now the key themes of discussion as the market wakes up to the risk of “greenwashing” – highlighted ahead of the climate summit when civil society groups urged Ban to prevent abuse in the Green bond market.

Stephanie Sfakianos, head of sustainable finance at BNP Paribas, said: “I think market participants are very cognisant of this. You do run the risk that an issuer can be potentially cutting corners on the greenness of the transaction, and it is a risk that people are very aware of. We are all making sure that issuers understand that taking a short cut would be an own goal of the worst possible kind, so I don’t think anyone is sleepwalking into that kind of disaster.”

Green Bond Principles

A key development earlier this year was agreement of the “Green Bond Principles”, voluntary best practices thrashed out by a consortium of investment banks, and subsequently of a structure to govern them under the International Capital Market Association.

But as attention to standards grows, so does the fear that imposing something more strenuous at this stage could do more harm than good.

“You do run the risk that an issuer can be potentially cutting corners on the greenness of the transaction, and it is a risk that people are very aware of. We are all making sure that issuers understand that taking a short cut would be an own goal of the worst possible kind, so I don’t think anyone is sleepwalking into that kind of disaster”

“Opinion is divided, there are still people – and I’m probably more at the stringent end – who feel we need to be relaxed, that the market won’t grow if we aren’t, but I think there are also people who also feel that there’s almost no point in this market if it isn’t going to be moderately stringent. I don’t think there’s a consensus – but people are aware there are dangers of that approach as well,” said Sfakianos.

There is nervousness because standards impose costs and while leading issuers such as the multilaterals have so far been shouldering these, this is less attractive in the corporate space.

Sabine Miltner, group sustainability officer at Deutsche Bank, said: “Mainstream investors want to avoid complicated standards that create additional costs and make their life more difficult. If the market, at this infant stage, is burdened with very prescriptive standards, I believe the market will be stunted.”

In divided situations, it is always best to look for the common ground. It is, at least, universally accepted that the market needs growing. It is also generally accepted that the right kind of growth is dependent on due diligence.

“These aren’t supposed to be one-off trades for a bit of PR and waving the flag – the true commitment behind this is ensuring that there is new liquidity, new funds going towards environmentally friendly projects, and raising the standards at all levels,” said Stuart McGregor, head of European SSA DCM at RBC.

Standards

When it comes to timing, opinions diverge: at what stage do standards need to be tightened? An incremental approach as the market matures and liquidity grows finds broad support.

“I think the consensus is that in the earlier stage standards have to be relatively open-ended, relatively broad and with the potential to strengthen further as there’s more confidence, otherwise we could completely stifle growth. It’s really about finding that place in the middle, but generally where everyone is leaning is towards a bit more permissive but still very transparent and enforced,” said Laura Nishikawa vice-president, ESG research at MSCI.

At the same time – standards that are too loose erode the distinctiveness of this market, making “balance” the new watchword.

“It is actually a very fine balancing act: everyone is very focused on the growth we have seen in this market. At the beginning of any market you want to encourage that growth, that innovation, you want to promote liquidity, which is important for investors and also to encourage new market entrants. However, issuers and investors want to encourage the highest possible standards in this developing market,” said Susan Barron, MD, frequent borrower origination at Barclays.

A next set of questions relates to the form standards should take and who should be their arbiters. The CBI favours a climate science-grounded approach – highlighting questions that must be asked about the extent to which investors are truly clued up about what is green.

A key focus in this debate is on issues of verification – the “second opinion” routinely sought by many issuers, at least in Europe – from ESG and green raters such as Cicero, Vigeo, Sustainalitics or DNV. Some investors feel verification does not add value, and methodology remains based largely against issuers’ own criteria. A key dilemma, therefore, is to determine what is, in fact, green – again fuelling arguments against rigid criteria.

Verification

Miltner at Deutsche Bank said: “I believe that verification is required, however, what is not needed at this stage is a precise definition of what is green and how green something should be in order to qualify to be called green. That is an investor choice, and most investors agree that there should not be a one-size-fits all approach.”

At the moment, “greenness” usually derives from a broader set of ESG critera applied by verifiers. A step forward has been the creation of the Climate Bond Standards and Certification Scheme co-ordinated by institutional investors and the tireless CBI. In June, proposed rules as to what buildings can be used to issue certified bonds were published.

Many market participants instinctively feel it must be up to investors to satisfy themselves about greenness – and hence able to choose.

“Investors will still take it on themselves – or should – to ensure that they fully understand and have the information about green issues. Some of the independent verifiers might argue that each potential investor is also asking for slightly different things. There is no standardisation among investors but this market is still in its infancy”

“Independent, third-party verifiers and ESG raters have a crucial role to play in ensuring that we build a Green bonds market firmly based on bulletproof environmental criteria that meet the needs of both issuers and investors, and we are actively talking with a number of colleagues in an effort to make progress on standards,”

As debates over the value and process of verification have deepened, the number of industry initiatives in this area have proliferated and the verifiers themselves are now talking.

“Independent, third-party verifiers and ESG raters have a crucial role to play in ensuring that we build a Green bonds market firmly based on bulletproof environmental criteria that meet the needs of both issuers and investors, and we are actively talking with a number of colleagues in an effort to make progress on standards,” said Daniel Rossetto, managing director of environmental business consultancy Climate Mundial.

There is no doubt that progress is being made as different groups and committees engage enthusiastically in conferences and discussions.

McGregor at RBC said: “Having some sort of market standard 12 months ago seemed like a long way away. We all know there are plenty of tests around the corner – what’s going to happen when an account doesn’t use these proceeds appropriately? It’s going to take several years to build up the criteria around issuing but step one was to get the visibility, focus and critical mass – and in the evolution of the market that’s where we are at.”

So if the watchword is balance, is this is achievable only through forms of intervention – or can market forces themselves generate solutions? Market-led initiatives are certainly sprouting up. Solactive was first to the market with a green bond index in March, S&P also compiles an index for labelled products, and Barclays and MSCI are poised to launch an ambitious competitor in November.

A key characteristic of these indices is that they represent a market-driven approach to establishing green criteria by responding to demand – the Barclays MSCI index is based on extensive consultation – while also offering a form of monitoring.

Nishikawa of MSCI said: “If you are looking at self-labelled bonds and even those that have a third-party second opinion at the time of issuance, there’s no follow-up to make sure that the proceeds actually were used for what was intended. What we will be doing is monitoring these on an on-going basis and a bond could actually be removed from the index if proceeds are diverted to another user or if there is a failure to report on where those proceeds are.”

Solutions of this kind raise broader questions about markets that ultimately return to the core global debate about growth versus protection – by asking whether a market free of rigid rules of engagement offers greater incentives for investing in the green economy in the first place.

Miltner at Deutsche Bank said: “The industry has struggled over recent years to prove that sustainability is profitable business. Sustainability is no longer just about creating a feel-good factor, it is important to demonstrate that it is profitable to be responsible and to be green.”

To see the digital version of this report, please click here.

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email gloria.balbastro@thomsonreuters.com.