IFR: Welcome to this IFR Roundtable on the future of IBD. The purpose of today’s discussion is to address some of the key questions around where this industry is headed. The majority of discourse around regulatory and strategic change in the investment banking sector has been focused on the trading businesses so I thought it would be instructive for us to evaluate how it is affecting how the origination businesses as conducted by the major firms.

It’s hard to have a conversation these days about any aspect of investment banking without people mentioning regulatory change. Thomas, if you had two or three key takeaways as to what the regulatory endeavour over the last three to four years is telling us in terms of how the direction of the industry needs to travel, how would you summarise it?

Thomas Huertas, EY: That the business be well capitalised, that the business be well controlled, and that the business ultimately be able to earn its cost of capital. Behind each of these objectives, regulators have undertaken a number of initiatives.

What Basel 3 has done is to put in place stronger capital. Regulators are now looking to firm up the foundations in terms of resolution. That’s important; it will have capital implications, including a greater emphasis on subordinated debt under total loss-absorbing capacity (TLAC). So banks will have a much stronger capital basis. But that created a knock-on effect in terms of reduction in inventory and problems with liquidity, particularly in the corporate bond market.

In terms of control, the speech delivered by the Governor of the Bank of England on June 10 at Mansion House (Building real markets for the good of the people) indicates the regulatory and official view. There’s certainly a great deal more to be done by the industry to create the public perception that banks have adequate controls in place. The fundamental business strategy issue is how does one meet the regulatory demands and still earn the cost of capital that will make the shareholders happy to continue to invest?

James Esposito, Goldman Sachs: When you think about regulation – on the investment banking side of the house not on the securities side – it’s having little to no impact in terms of how we deliver our services to clients whether that’s advisory, whether that’s equity or debt underwriting. The key, though, when you speak about regulation, is the impact that it’s having on banks’ returns on capital, and so the single biggest issue plaguing the global banking industry right now is lack of return on capital.

The vast majority of banks, particularly in Europe, are not generating their cost of capital right now and so the global investment banking model is incredibly expensive to get right; you have to be in all three major time zones, you have to have excellent people prepared to do a lot of client service in regions that might not be particularly profitable.

As banks are being asked to hold a lot more in the way of capital and a lot more in the way of liquidity, that global and expensive model looks that much more challenged. So, for me, when you think about investment banking – again not securities – it’s not so much re-regulation of our industry that’s the challenge; it’s the lack of ROE, and banks are really struggling with that right now.

IFR: Ted, from your perspective, the banks are responding to those challenges in quite a lot of different ways. What’s your read of how the investment banks have succeeded in getting the joke, as it were, and are reviewing and updating their business models?

Ted Moynihan, Oliver Wyman: The investment banking industry has been living under a serious cloud for a number of years. First of all, there are a lot of positive things that we could say today about the IBD end of the business. I see very interesting things happening with this group’s corporate client base: a lot more confidence to use its cash, a lot more confidence to finance itself in longer term, more structural ways to refinance itself. All of that is good.

You see a resurgence of the FIG market beginning to come in, where there has been a phoney war over the last few years sorting out problems on its balance sheet, and that will be good for the economy and good for the investment banking industry. The market structure has responded, we’re getting deepening of the DCM markets. That’s good. We’re getting more high-velocity turnover of the balance sheets, which is required and that’s good. CLOs are coming back into the market; that’s all good.

On the sell side, the economics have improved and banks have learned. They’ve had to run very hard to be fitter and leaner and run on less capital and with lower levels of leverage and balance sheet. Particularly in regions like Europe and Asia, which were deeply underwater in terms of their economics, there has been some positive signs particularly last year.

When you look forward, you can’t be complacent; there are a number of things that the industry still needs to focus on. The regulatory programme is going to push a significant further level of tightening on the costs of leverage, liquidity and funding. There’s still, by our calculation for any investment bank, probably another 2-3% of ROE drag that’s going to come from the stuff that’s still coming in the next two to three years. We’ve already absorbed 6%-7% by the way.

That’s big and it does affect the way you run an investment banking division. The industry still needs to focus on things like the pricing of loan facilities in the European market, which just have never really responded properly. There’s a lot of mispricing, even still today in the market, that just needs to respond better.

On the risk side of the equation, our concerns are less on the underwriting side of things. There’s been a massive shift towards accelerated bookbuilding and we’re quite glad to see that the leveraged loan market seems to have engineered a softer landing than people feared last year. The risks from our point of view are much more on the secondary side of the equation and whether we are creating bubbles which are misunderstood and can’t be managed.

That may, in fact, mean on the origination side of the business we have to make some adjustments. We think some standardisation in the loan markets, for example, which are wonderfully flexible markets, might be a good thing. And then continuing to just tighten up the way the businesses are run. There’s much more of that to do.

IFR: On this notion of earning your cost of capital plus, Europe is stuck in a slightly more convoluted regulatory environment than perhaps is the case in the US. How do the European banks need to respond to this in terms of how they evolve over the next two to three years?

John Langley, Barclays: The first thing to say, to Jim’s point, is that investment banking is still very much a global business; our clients are global and we have to think about that in the way we define our strategy. As the industry moves towards a more returns-based model, it reinforces the importance of allocating capital to support long-term client relationships as opposed to short-term revenue streams.

Although European banks have had to deal with some of these challenges perhaps quicker and earlier, it feels to me that regulatory pressures are being felt more broadly. It really sharpens the mind in terms of what the client proposition is from an investment banking perspective. That has been very important in our journey at Barclays. Clearly defining our client proposition; being very clear on where we can add value; playing to our strengths; and being consistent globally. The days of trying to be all things to all people are no longer realistic from a cost and capital perspective.

IFR: Saul, allocating capital optimally sounds easy but investment banks haven’t traditionally always been particularly good at pricing and allocating risk because it wasn’t really required in the revenue model John referenced. Are you, as an industry, up to the challenge of making the required transition?

Saul Nathan, Morgan Stanley: It depends who you ask. For our part we’ve operated a business which is very focused on return on capital for a really long time, and certainly well before the regulators demanded more from banks in this area. You can’t operate a model which doesn’t earn its cost of capital; it’s not sustainable. I think John’s right that you have to be in the businesses where you have real competitive advantages, but there are some markets which today, I think as Jim said, where the pricing still isn’t quite aligned and there’s a-ways to go.

We’re very conscious that we have to measure each of the decisions we make, whether it’s in how we allocate balance sheet or how we use capital and how we price things, so that they produce the kind of returns we think are appropriate for our business on a risk-adjusted basis. We’ve been doing that for a very long time; it hasn’t necessarily made us the most competitive bank in some situations.

We see that sometimes in the financial sponsors business, where loans are sometimes priced very, very aggressively at a level where we can’t make a return on capital that makes sense on a risk-adjusted basis. There are others who are willing to do that, and until we get more people with the same sort of disciplines, that will continue.

James Esposito, Goldman Sachs: The thing that caught us perhaps by surprise is we would have guessed by now we would have had an even more accelerated pace of change. We’ve seen the banking system go through some evolutionary shifts: banks are getting out of certain lines of business; there’s been a bit of balance sheet shrinkage in Europe. We would have thought you would have gotten a lot more of that by now.

The thing that we probably underestimated was the impact of QE. Clearly, central banks are propping up liquidity in capital markets and that’s having a materially positive impact on the banking system. If you were a betting man or woman, you’d guess QE is going to last for quite some time, so that state is going to continue.

There’s no proverbial gun to the head of the banking system right now but what I would anticipate is it might not be the funding markets that pull the plug and force more revolutionary change on the banking system; it very well may be the equity markets. I’m surprised how patient the shareholder has been in the banking system when they’re not meeting their cost of capital.

I would have guessed it was going to be the funding markets. It wasn’t; the ECB stepped in and provided liquidity. That allowed banks a bridge to the other side where they didn’t have to go through a big downsizing. Now I’ll be surprised if over the next three to five years the equity markets are as patient as they’ve been to date.

IFR: Sophie, mispricing has often been used as a competitive tool amongst the banks, and this has long played into the competitive landscape, which is clearly changing now. Mispricing has been used to win business in order to leverage cross-sell and ancillary business. How is this notion of business re-pricing and having a much more realistic perspective playing out in the new emerging world?

Sophie Javary, BNP Paribas: We are on the eve of some sort of consolidation in Europe and a differentiation between European banks that are global and at par with their US counterparts, and those which are going to be regional or playing in only a few elements of IBD.

One of the major changes affecting the European banking industry will be single supervision by the ECB. We are at the start of this and what it will drive is a single market for banking which we haven’t had until now. This is a major development and one which will, under the pressure of the ECB, put an end to mispricing and some of the non-rational calculations we see in some elements. We see the ECB as having a major impact on the banks that are supervised and will have to work on a more level-playing field.

The fact that some regional domestic banks were pushed by their own regulators to engage in unfair competition is going to stop. That’s one element of your answer.

The second element is the fact that in banks like BNP Paribas and others, we need to see IBD not as a single business separated from the rest but completely integrated into what we do vis-à-vis small businesses, vis-à-vis our domestic banking network. The real shift of medium-sized companies towards capital markets is being helped by the IB division. The way we see it is that IBD cannot be an isolated part of a bank; it has to have a purpose of serving long-term relationships.

This question of long-term relationships is also very important because we are in a world where our clients are finding it difficult to see the difference between long-term relationships and optimising every penny on every transaction.

One of the things our corporate clients must consider is who their long-term partners are, in case we go back to more difficult times. There are not that many banks that could support their strategy. What we, as investment bankers, have to do is to demonstrate that we are there to help the real economy; that we have amended our code of conduct and we are there for the long run. That alliance between the corporate/institutional world and the banks has been cut and needs to be restored.

IFR: There are a lot of themes embedded in that answer. William, some banks have made a lot of difficult changes; some by choice; others forced on them. How do clients see this process? How do they figure out who their long-term partners are in this environment?

William Vereker, UBS: About banks having made a lot of difficult choices, I’d suggest that there’re more difficult choices ahead of banks than behind them. We’ve got to where we are today because of three factors all coinciding with one another.

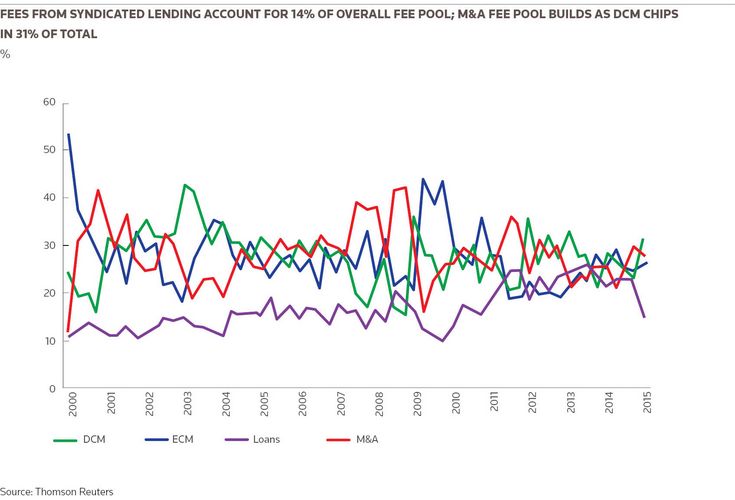

One is the regulatory changes we’ve been talking about; two is the decline in Europe of the fee pool, the absolute reduction in the revenue opportunity with some, but not a lot of, reduction in market participants; and three, an inability to-date of most organisations to really address their cost bases; the cost base has not in any way kept track with the decline in the market.

Different banks have responded in different ways to the pressures that that decline has created on returns. But a lot more hard decisions need to be taken by financial institutions over the course of the next two or three years in the face of that, because those fundamental dynamics are not going to change. In fact, they’re probably going to get reinforced.

Turning to your question about clients, it clearly means that institutions have to focus on what they’re good at, and allocate their capital in those directions; align themselves with a client base which is suited to what they’re good at. And we’re seeing that. Different institutions have reacted at different speeds, which is arguably why you’re starting to see a difference in returns between different banks. But there is going to be an increasing differentiation and distinction between business models and how banks address this. There’s going to be a lot of change, therefore, over the next two years.

To see the digital version of this roundtable, please click here .

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email gloria.balbastro@thomsonreuters.com