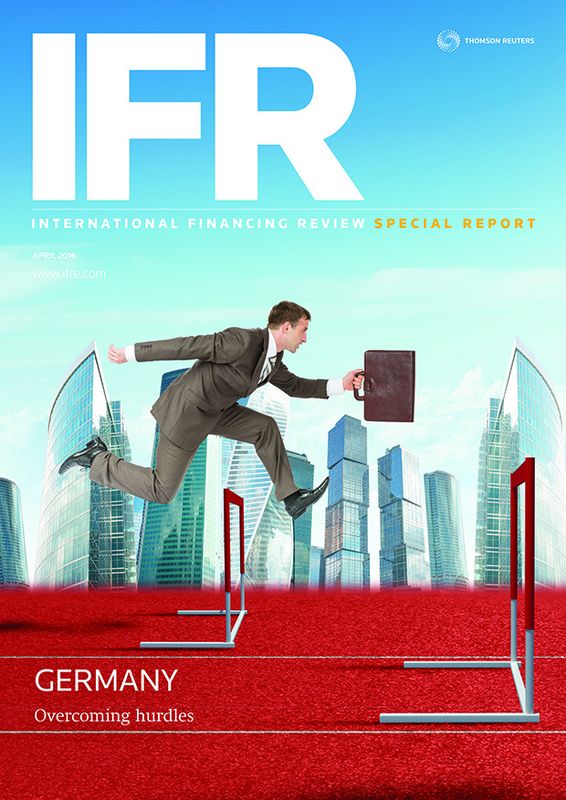

Overcoming hurdles: With attention more often than not focused on other parts of the eurozone and the problems faced by countries mainly in the southern part of the region, it is easy to forget that Germany is not without issues of its own.

Its much-vaunted auto industry, for example, was rocked by the Volkswagen emissions scandal that broke in September 2015. The sector has long since been a mainstay of the country’s corporate world, so the revelations and their consequences cut deep into national pride.

That the credit has been partially rehabilitated and that the ABS market provided an avenue to funding in the interim have both been greeted as positives, although the road to redemption looks to be a long one.

ECB initiatives to include corporate debt in its bond-buying programme have added a further spring to the sector’s step, although previous experience in the Pfandbrief market shows that such action can be a double-edged sword, impacting liquidity and contracting spreads to such an extent that the traditional buyer base no longer finds the product so attractive.

Germany’s corporate borrowers have not historically encountered problems as far as market access is concerned – VW notwithstanding – so whether the negatives will outweigh the positives is a moot point. On the other hand, those further down the food chain could benefit from an investor community looking for incremental returns in a low-rate environment.

In fact, it looks as if it is the equity rather than debt market that could do with a helping hand as far as corporates are concerned, with just one IPO bigger than US$50m pricing so far in 2016. That deal, from wind turbine company Senvion, was initially cancelled after bookbuilding, only to be resurrected as a restructured but far smaller trade in fairly short order.

But it is this very willingness and ability to adapt to the conditions that leads bankers to believe that all in ECM is not necessarily lost in spite of a lacklustre DAX and heightened volatility. The previous three German IPOs were also downsized in order to get them over the finishing line, and this Realpolitik paid off inasmuch as their subsequent performance was commendable. By contrast, those that chose to cancel rather than tailor their aspirations to the conditions have little chance of trying their luck again any time soon.

The story is similar in the financials world, where close on 1,800 banks are fighting it out to attract business, giving one of Europe’s most advanced nations a rather antiquated feel. Consolidation – which some would deem the natural manner in which to adapt to the circumstances – has been slow. A reduction of 200 since the financial crisis might sound material in isolation, although it is not nearly so remarkable when starting from such a high base.

Returns are low and aggregate profits are down to levels seen last century. Lending is stagnant – exacerbated by the conservative nature of those on both sides of the equation – with the lack of any domestic crisis prolonging this inertia. But perhaps as other countries move to address their predicaments, this will change.

There is, however, one area in which the German banking industry stole a march on its rivals – although not all are agreed it was in a good way, investors in particular. In November 2015, the Resolution Mechanism Act was passed, subordinating senior unsecured bonds to deposits and derivatives.

This aggressive bail-in approach removes the need for German banks to raise billions of euros of additional loss-absorbing debt to meet European and global regulatory requirements, given that it will be retroactive when it takes effect in January 2017. However, there are concerns about the senior debt market becoming a minefield for investors, with the regime likely to be just one of a patchwork of approaches across countries.

For all that is going on in the financial markets, there is one subject that is more talked about than any other – immigration. But even here, the two subjects are intrinsically intertwined, with KfW, the country’s development bank, upping its 2016 funding target by €12.5bn, largely as a result of the refugee situation.

The reason for the need to change may be different from those facing the corporate, banking and ECM worlds, although it is just one more hurdle to overcome.

<object id="__symantecPKIClientMessenger" style="display: none;" data-extension-version="0.4.0.129" data-install-updates-user-configuration="true"></object>

To see the digital version of this special report, please click here

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email gloria.balbastro@thomsonreuters.com

<object id="__symantecPKIClientMessenger" style="display: none;" data-extension-version="0.4.0.129" data-install-updates-user-configuration="true"></object>

<object id="__symantecPKIClientMessenger" style="display: none;" data-extension-version="0.4.0.129" data-install-updates-user-configuration="true"></object>