IFR Asia: Let’s maybe try and take a few questions from the audience, if we can.

AUDIENCE: I’m Barbara Stallings from Brown University. This panel was obviously set up to talk about debt markets, but capital markets do include equity markets. With two possible exceptions, Mr Das and Mr Sternberg with casual mentions of the Indian equity markets, nothing.

I wonder if anyone could say anything about the equity markets in Asia and how they link to corporate bond markets in the region? Thank you.

MONISH MAHURKAR, IFC: I think, partly, the reason why the panel focused so much on fixed income is that most of us are under the impression that, in most of Asia, equity markets are relatively further along in terms of development. They are mostly open. We took the example of India, of Stock Connect in China. It’s a bit of a paradox that regulators in general have been much more open and accepting of volatility, inflow and outflows, and openness with equity markets than they have been in the debt markets. Some of that could be because debt markets also get closely linked with monetary policy issues, interest rate issues, FX controls etc., so maybe there is a little bit of regulatory overlap challenges there.

But that’s the reason, I think, because equity markets are more open.

ARNAB DAS, INVESCO: If I could just add to that, I would suggest that another very related factor is that, as was said earlier, policy makers prefer stability to instability, for obvious reasons. When the equity market comes under a lot of pressure, equity prices fall, and that’s a challenge for the companies, maybe it’s for the issuers of equity, it’s a challenge for domestic investors. It may not be such a challenge for the entire economy. If the currency falls, while that might be a bit of a problem, it might help with some adjustment to whatever shock is taking place.

But if your bond market is heavily owned by foreign investors, that’s different. If you take the case of Indonesia, I believe 40%, or maybe a bit more at the moment, of the Indonesian bond market is held by foreign investors. So it’s quite possible that, in the function of Bank Indonesia, keeping that stable is actually quite important.

I suspect that policy makers in a large, politically challenging country like India or possibly even China might have some issues with a lot of volatility in the bond market that transmits directly into the banking system and into the financial system more broadly. That’s why I think this whole issue of sequencing is very important, that you get your domestic markets to be as liquid and deep and efficient as you can before you open them up to the vagaries of people like ourselves.

AUDIENCE: Hi, my name is Thomas Pellerin from IFC World Bank Group. Until just now, all we heard is about India and China. Outside of the two elephants that we mentioned, I’d be really willing to hear from the panel about the tigers of Vietnam, Indonesia, Philippines, Malaysia. It seems to me that these economies are still extremely protective in terms of capital inflows. Are we seeing a little bit of one step forward, one step backwards? Or sometimes two steps backwards? I’m happy to hear from the panels on these specific economies.

EDDY STERNBERG, LOOMIS SAYLES: If I may, the one step forward and two steps backwards is very prevalent in the region. Malaysia is a case in point. It’s also very important in our emerging market benchmarks. It was quite open. Actually, the ownership of foreigners was much higher than that in Indonesia. It was probably around 60% at some point in time, maybe even higher than that.

For some reason, Bank Negara decided that that was not convenient. It had a currency which is quite controlled to begin with, and put in steps that make it less attractive for investors to participate in the market. You could hedge if you needed to hedge, then it became a little bit less restrictive but it was not quite clear, to the point where the benchmark or index provider decided to not keep adding new bonds as maturing bonds come out.. They decided not to include new bonds that were coming into the universe, issued by the government, and that’s an issue for us.

That’s maybe another thing we should have been discussing, but not something that makes investors very happy. We shy away from those markets. The smaller markets are not part of benchmarks and we’re still interested. Sri Lanka is a market that we’ve participated in. On Vietnam, as I said before, I’m an old-style emerging market investor, and low yields are not very attractive to us. Vietnam doesn’t pay very high yields in its domestic market.

IFR Asia: Monish, when you look at frontier markets in Asia and around the world, how do you decide when they ready to start engaging international investors?

MONISH MAHURKAR, IFC: Again, it’s challenging, and we find a whole spectrum of countries out there who are willing to look at this. I already mentioned this example of Rwanda, which is actually surprisingly open-minded, although the market is really undeveloped, very basic. But we have actually managed to issue a Rwandan franc bond in the domestic market and an offshore Rwandan franc-linked instrument. Of course, in these markets, these tend to be isolated and one-offs. It’s just a way of starting the process, but it takes time.

There’s a discussion ongoing in markets like Nepal, where we have some projects coming up in hydropower and we would be happy to issue a Nepalese rupee bond, and we have some framework of approvals there. We’re in discussions around going into Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, it’s just that it takes time to make the policy-makers comfortable, and some of those issues around crowding out and finding a balance between different priorities acquires a little more profile there, so you have to be a little more careful.

I think we’re happy to engage, as long as there are projects to finance and there are regulators who are open-minded.

BILL FOSTER, MOODY’S: I cover several Asian frontier markets, and I would just add that you never have the perfect situation coming to market, but you want to ideally do it from a position of strength, where the policy framework is sound, debt leverages are relatively low, fiscal policy is under control, and ideally you have a flexible exchange rate to absorb shocks. That’s not always the case.

You want to at least have the conviction to be able to do the right things and the agreement from a political and economic perspective that, if things get challenging, you’ll have policy responses that will be generally prudent. You don’t want to be put in a difficult situation moving forward just because you’ve issued and gone to the market.

If you look at places like Sri Lanka, like Mongolia, like Pakistan, these are very interesting markets, but they also suffered issues over the last few years in terms of accumulating a lot of debt. There have been issues around foreign currency debt because of depreciation. So, these are very important things for governments to consider before going to the market because it will get increasingly difficult for them moving forward if they don’t do it in a responsible fashion.

ALEXI CHAN, HSBC: If we think broadly about what we’re trying to achieve here, it’s quite multi-dimensional. We’ve talked a lot about how we can bring international investors into the Asian capital markets, and that dimension is similar but not identical to the currency angle we’ve talked about.

Clearly, the biggest developments we’ve seen in the last five years have been around a large dollar denominated bond market growing up in Asia with significant participation from international investors – be they in London, in Boston, or closer to home in the region. The third dimension, which we haven’t really talked about today, is actually the development of a true credit market in Asia. I think this ties in to the point about equity versus debt.

We’ve actually seen a lot of international investors want to take a view on the currency via their participation in local government bonds, so the 40% foreign participation that we’re talking about in Indonesia is largely a rates and currency position, rather than a credit position. From our perspective, the credit dimension has also progressed pretty well, largely in hard currency, so this year we’ve seen a range of issuers come to the high-yield international bond market. We’ve seen infrastructure financings out of Indonesia, in the IPP space, out of India, in the airport space.

I think developing a credit market in Asia is also as worthy a goal as developing a local currency market and as bringing in international investors. Now, how these three dimensions line up at any one time will depend on the progress we make on each of them, but all of them are worthy of pushing forward, and I think it would be a mistake to judge the overall picture by insisting on trying to cover all three of these dimensions in every financing.

I think on each parameter we’ve made significant progress, and as the region opens up and becomes more intertwined, I think there’s a lot of cause to be optimistic.

AUDIENCE: I’m from China, so I would love to know your opinions and views towards the Chinese financial markets. How do you foresee the risk in the high leverage in China’s debt market?

The second question is about the Chinese equity market. Do you understand the real reason behind the 2015 stock market meltdown? The third question is about internationalisation of Chinese markets. What are the necessary conditions to let the Chinese regulators feel comfortable to loosen their capital controls? Thank you.

ARNAB DAS, INVESCO: Three very easy questions!. First, on the debt ratios and the leverage problem, it clearly is a challenge. We haven’t seen these kinds of rates of credit growth in most countries for some time. What has improved in the last couple of quarters is that the ratio of credit to GDP has stabilised. That seems to be not because credit growth has slowed down sharply, but because nominal GDP growth has accelerated quite a lot because producer price inflation has picked up.

Nominal GDP growth in 2015 – when people were really scared about this – was quite low. There was quite a lot of doubt about the real GDP growth numbers, and PPI was in deflation. So, credit was growing quite rapidly, and the denominator was growing much less rapidly so that debt ratios seemed to be on an explosive trajectory which, among other things, was quite worrying. Since then, like I say, the nominal GDP growth rate has picked up.

People say there’s been deleveraging, or at least a slowdown in the growth rate of leverage, and I guess what they really mean is in the total stock of debt. It doesn’t appear that TSF – Total Social Financing – has actually slowed down. The problem will probably be contained if China can keep nominal GDP growth up, if it’s choosing not to slow down TSF, which it appears not to be willing to do. Assuming growth is a very important target, as it seems to be, I think we can expect that to continue.

Is that going to lead to a credit problem, or some sort of event in the banking system? Well, there’s certainly reason for concern, but what I would suggest here is that, unlike many other countries where those kinds of challenges have become a crisis, a lot of this is taking place within the state sector. You have a number of state-owned banks lending to a number of state-owned enterprises and you have a quasi-fiscal guarantee there. I think the Chinese people and Chinese firms and banks understand this.

So, in some sense, that’s stabilising. I’m not suggesting that it’s ultimately a good thing or the right thing to keep that arrangement. But it will probably allow for much higher ratios of debt to GDP than in many other quote-unquote emerging market countries.

IFR Asia: Just to wrap up on China, because we had a lot of other hands up there, if China opened the capital borders tomorrow, all the money would flow out, wouldn’t it?

ALEXI CHAN, HSBC: Steve, I’m not sure that’s really the right question. From our perspective, this is a huge exercise that China is undertaking to reform its economy, to gradually open up the capital market, and to make the transition to more private sector entities and world-beating companies. We’re already seeing many successes in technology and other sectors.

From our perspective, the market’s view on China today is significantly more positive than perhaps when we were all gathering for these meetings 24 months ago. We’re seeing the foreign exchange reserves go up, the currency has appreciated. In terms of the point about liberalisation, really, this needs to be done at the appropriate pace for the Chinese financial system.

I think some of the teething issues that we’ve talked about in terms of how investors and issuers can get access to the domestic market are inevitable elements of that gradual opening up, which has to be the case for this market to happen in a conducive way for China.

BILL FOSTER, MOODY’S: The other important factor, to add to what you’re saying about growth and deleveraging is you also have to see a restructuring of state-owned enterprises so that they become more efficient over time, because this is very credit-intensive growth. If you look at the ICOR ratios, it’s very inefficient. For a nominal level of GDP growth to be able to bring down that debt over time, you need to see greater efficiency in the allocation of each dollar of capital.

That would be an important aspect of the reform agenda, as we’re all aware, and how that pans out will certainly be a big deciding factor in how the deleveraging story plays out.

AUDIENCE: I’m a private equity investor in asset management companies. When you think of timing, I would like your guess in terms of how many years until China’s and India’s markets are liquid, open. And I’m talking about credit markets, not the FX market we have today. I know I’m asking a lot, but is it three, five, seven, 10 years?

Many fund management companies are thinking about building products for their end investors, and they don’t know really how to plan for it, because they’ve been told that these markets will open up for years.

EDDY STERNBERG, LOOMIS SAYLES: I won’t venture a number, but despite everything I’ve been saying, we’ve seen China really moving very, very fast. I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s a handful of years as opposed to two hands. In the case of India, it’s true. We’ve heard about the opening of their markets for probably 10 years now, and it’s always two years down the road.

IFR Asia: Does anybody else want to take a stand with a number?

MONISH MAHURKAR, IFC: I’m not sure if it’s the right way to look at emerging markets in general, because it’s a long process. In some ways, the opportunity for fund managers, I don’t think in these markets is a case of waiting to see when they fall neatly within an index, and you can build simple products to offer investment opportunities in these markets.

I think, for a while to come, you have to look at these more as alpha opportunities, not as index opportunities. That’s where I think those who are alive to those opportunities are already exploiting them. I don’t think they are waiting to create products when these markets will be fully set up because it’s not a linear path.

BILL FOSTER, MOODY’S: I’ll say one thing about India. I don’t have a number for you, but what you can look at to get a sense as to when they may move is really the fiscal deficit and the debt levels in the system. They need to finance that in an affordable way and, ultimately, they use the banking system to do that.

When they’re in a more comfortable fiscal position moving forward, that’s when I think you might see more space for reform.

AUDIENCE: I’m wondering if our panellists could say a little bit about the state of play of the forward markets and the ability of investors to hedge in these markets, in terms of spreads, size –particularly in some of the smaller markets like Philippines, Malaysia, and so on.

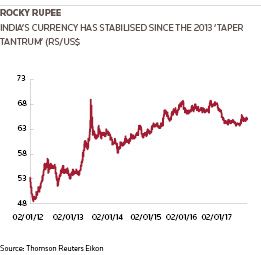

EDDY STERNBERG, LOOMIS SAYLES: It’s not great. When I think of an open market, an easy market to do all these things, both to invest and to hedge and use forward markets, think of Mexico. It’s outside the region, but it’s a good example also of a market that opened up fast with a good, local investor base with growing pension funds and foreign participation. It opened very, very fast from 1996, where it had a three-month T-Bill. By 2006, so not even 10 years later, it had a 30-year bond. Foreign participants helped a lot. They had the ability to invest just the same way as local investors, but also the ability to use all these instruments to hedge. Despite it being so open, it went through a crisis. 2008 was a huge crisis that affected Mexico, not as an internal intrinsic crisis, but as an external one, and it fared quite well. Even in the 2013 taper tantrum, it all worked. It doesn’t work that well in most Asian countries.

AUDIENCE: Thank you. My question is actually in regards to distributed ledger technology, the DLT and blockchain space. There have been recent advancements that show it can now offer scale, investor protection, and ease the flow of capital compared to a lot of traditional financial instruments. China is now talking about launching a federal block chain currency in as early as 2019. How do you see distributed ledger technology impacting global financial markets and the liquidity of capital in the next three to five years?

ALEXI CHAN, HSBC: Well, we’ve seen the use of some of this technology in some of the European markets. Already in the private placement markets we saw one of the large German company issue a Schuldschein instrument using this sort of distributed ledger technology. I think the potential for simpler processes and efficiency to be brought into capital markets is absolutely there, from a technology point of view.

From my perspective, we’re very much alive to how new processes and new technology can help link issuers and investors around the world in the most efficient manner. One can’t assume that the current approach of bookbuilding, roadshows, distribution of offering memoranda via Bloomberg and other existing technology is going to remain the way that the markets do business.

Whether we’re talking about changes to the efficiency of how we can connect specific investors to specific financing requirements, or whether we’re talking about a fundamental shift in the markets, to me is the critical question. Clearly there are efficiency gains in how we do business.

We’ve invested, for example, in a platform that gives investors direct access to the bookbuilding process, so we’re cutting out a number of stages that, frankly, were not adding significant value to the overall execution of a placement.But it remains to be seen exactly how technology is going to fundamentally change the game.

AUDIENCE: How do you get global pension funds to look at emerging markets, because the rating itself is a constraint? What we need is long-term money. How do we widen the investor base?

ARNAB DAS, INVESCO: If I could start, my impression is that there’s quite a lot of institutional investor interest, from pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, endowments, you name it. I think many of them are quite active. We have significant amounts of institutional client money of those categories that has been very active in emerging markets for quite some time.

Actually, since the GFC, that interest has, if anything, grown quite significantly because we’re in a low growth, low inflation world. Maybe we’re not talking about old-style emerging market yields, but if you want higher yields than are on offer in the developed world, that’s where you’re going to go.

MONISH MAHURKAR, IFC: For pension funds and for long-term insurance investors, it plays a bit differently from the kind of discussion we had today about investors looking for a combination of rates and FX, which is more a short- to medium-term play. For pension fund investors, it’s about stable, long-term cash flow.

I think the best fit to my mind is the infrastructure investment opportunities in markets like India, China, Brazil, Mexico, or even the next tier of developing markets. That’s a less bond-friendly play, but there are again intermediate instruments that can help us get there.

One instrument which we’ve had some success with in the last couple of years is something we call a managed co-lending portfolio programme. Over the past year, we have signed up about four or five global insurance funds, where they will co-invest with us in a diversified portfolio of infrastructure assets. This is infrastructure loans, so it’s not in a bond format.

Another instrument, where you’ve seen some effort but haven’t had as much success – at least so far – is this idea of an infrastructure bond. You can get an infrastructure company to issue a bond, but then to meet the ratings threshold, somebody has to step in, either a development institution or another commercial financial institution, to wrap the credit. From what we’ve experienced, at least during the construction phase of the project when the risk is very high, most pension funds would not take that kind of construction risk at the greenfield stage.

So there are, again, some instruments which are beginning to make an appearance, but it’s early days.

AUDIENCE: Hi, this is Nipa Sheth from Trust Group, India. I had a question around the infrastructure market. When we see Masala bonds, or even when we see foreign interest in the domestic market, most of it is in AAA, short maturities, or sovereign risk. How do you open up a market for financings which are slightly lower than AAA? India has a huge need for infrastructure financing, and many of these projects may not be greenfield – they’re already mature. Is there any way one can address this in either Masala bonds or through foreign investment?

BILL FOSTER, MOODY’S: As you’re probably aware, a lot has been done on this front over the last few years, in infrastructure investment funds, IDFs. There’s a whole lot the government has done over the last 10 years to focus on ways to bring specifically long-term money into infrastructure in India. You need credit enhancement, you need to have foreign exchange hedging to mitigate the risk there.

Then the question is, who’s going to provide sovereign guarantees? Is it going to be the government or is it going to be a tripartite agreement with some kind of government authority? It gets a bit complicated, because ultimately these become more costly, but risk mitigation is key for foreign investors looking for a higher rating.

I know the government has talked in the past to multilaterals about providing guarantees as well. The issue around it, though, is it becomes more expensive for the issuer and for the government to provide the assurances that foreign investors need for it to be deemed safe paper. That’s what I’ve seen, at least.

MONISH MAHURKAR, IFC: On infrastructure, the upside is that it’s a classic, ideal asset for long-term investors because once it goes operational, it’s steady cash flow. But to get there, the issues around the greenfield, construction stage do create lots of complications.

The other aspect is that, to connect it back to the capital markets, there is a certain amount of stabilisation of cash flow that you need to create. A typical infrastructure project follows its own curve, with disbursement over a period of time and then amortisation etc. Those are some challenges that I don’t think have been fully overcome yet.

ALEXI CHAN, HSBC: On the hard currency side, we’ve actually seen some quite interesting transactions this year in the infrastructure space that leave me feeling quite encouraged. So, in airports, we’ve been involved in a very large financing for the new Mexico City Airport, and this involved a mix of loan and bond financing, and the bond financing had very long tenors out as far as 30 years.

Closer to home, I mentioned earlier in the energy space in Indonesia, we structured an investment-grade financing for PT Paiton Energy, which was really the first large-scale project bond out of Asia. By using project finance techniques to mitigate some of the challenges that Monish has mentioned, we managed to achieve a Triple B rating and access very long-dated money in the international markets.

I think it’s important to sometimes distinguish the currency elements and the credit elements, and I think infrastructure is actually an exciting space where there are a range of techniques out there. Whether all of those will play out in the local markets with international investors, we’ll see over time, but certainly the space has advanced quite significantly this year.

IFR Asia: Ladies and gentlemen, we are out of time. Thank you very much for some great questions, and please join me in thanking our panel.

To see the digital version of this roundtable, please click here

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email gloria.balbastro@tr.com