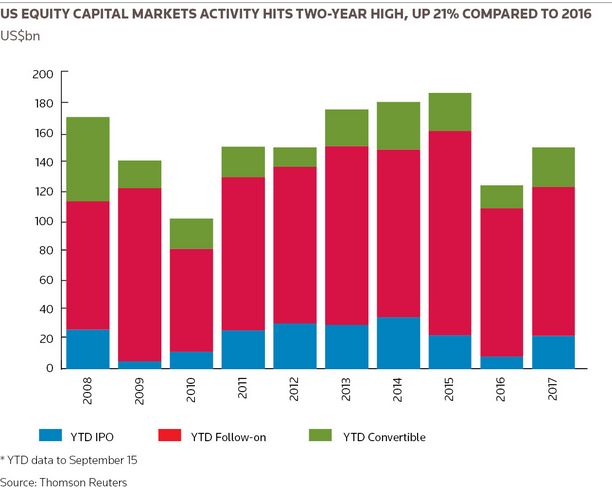

IFR: US ECM activity is actually up about 20% this year, and IPO volumes are up as well. but not really to levels that some people might have expected at the start of the year. For many that is surprising, particularly when we have the stock market indexes at record highs almost daily. Anna, why aren’t there more deals?

Anna Pinedo: I think that there’s a lot of private capital available. There are more sources of private capital than ever before, with crossover funds, family offices, sovereign wealth funds, etc. It used to be the case that, when companies came to us to talk about a public offering, one of their principal goals was raising capital. They can do that now in the private markets, and in many ways they can do that more cheaply.

Another age-old reason for going public was to provide liquidity opportunities for existing security holders. Now, with the development of private secondary markets, there’s a way to do that without going public, so it’s a very different conversation with clients now when they’re weighing an IPO. It’s not necessarily because they need the capital. They have other ways to recruit and retain employees and provide liquidity. It is oftentimes because they intend to pursue an acquisition strategy, or for a variety of other reasons.

The costs of going public have not gone down, even with the JOBS Act. That remains a concern. Once companies go public, obviously they’re subject to intensive scrutiny, and they’re subject to litigation risk. For a lot of entrepreneurs, having to report quarterly earnings and pressure on them to deliver on a quarterly basis – perhaps while giving less attention to long-term investment – is unappealing to many.

The new SEC chair [Jay Clayton] and the SEC as a whole certainly has said all the right things in terms of being very committed to promoting capital formation, while striking the right balance between capital formation and regulatory burden.

They’ve shown that through the new policy of making confidential submissions more broadly available, so we certainly expect there’ll be more changes ahead.

IFR: Sticking with the JOBS Act, Brett, its basic goal was to facilitate capital formation for small companies. Has it lived up to that goal?

Brett Paschke: There are a lot of notable successes on the small company front that were very much influenced by the JOBS Act.

The biggest category is life sciences. We’ve seen a real increase in the number of IPOs by small pre-revenue or very low-revenue life sciences companies that very much benefit from some of the lower requirements of the JOBS Act. They tend to be smaller organisations, more scientifically oriented, and have small staffs until they get through the FDA process.

You’ve seen major growth in that area. Hopefully that has some good long-term benefits for the world as a whole, because the drug discovery process is getting funding in ways that it hasn’t before. The life sciences sector is the poster child on the success side.

For the broader market, it’s had an impact on the ease of raising capital as a lot of the JOBS Act provisions have now been extended to larger companies in the IPO process, but even in public companies now you’re able to file confidentially for a follow-on offering in certain cases.

The dynamic has definitely changed. Ten years ago we’d meet with companies it was: “Can I get public?” Now when we meet with companies it’s: “Why should I go public?” The burden is on us to explain the benefits.

Once companies are public, the ability to raise capital in different ways – quicker, more easily, overnight, fast, without a big burden on the company; secondary shares, primary shares, whatever they need – has never been as good as this.

One of the primary reasons that people ought to be looking at going public is that the JOBS Act, while it may have had an unintended consequence, has really helped speed up the capital raising process.

IFR: The IPOs of social messaging service Snap and meal-kit delivery service Blue Apron were somewhat disappointing, to say the least. Passi, could you comment a little bit about the state of the IPO market, and tech in particular, and whether the model is broken?

Pawan Passi: Thanks for the easy question! [Audience laughter] Not to challenge the question, but obviously Snap did trade up on day one, and meaningfully so. It wasn’t until two earnings reports that it actually broke issue, but it goes back to a couple of things.

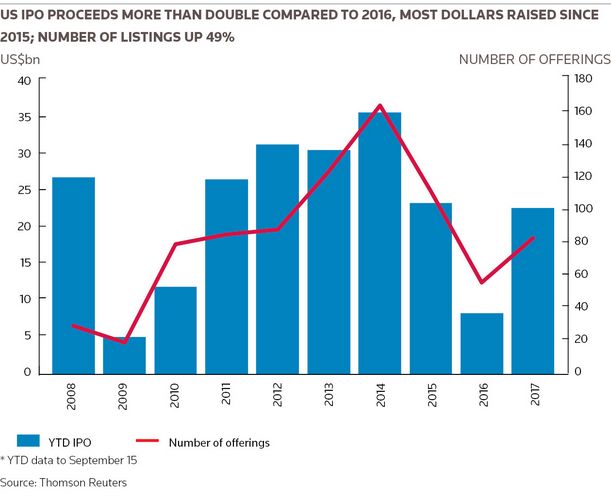

There hasn’t been a lot of IPO product. Actually if you look at the average performance of IPOs this year, it’s been one of the best years for IPO performance, certainly vis-a-vis last year, and even the year prior. IPO performance has been good, notwithstanding the two case studies you decided to select.

The other point I would make – and I think this is a big part of having this discussion – is one of the luxuries that companies are now able to enjoy, whether it’s the JOBS Act or whether it’s through private capital, is they can spend more time privately understanding their business model and developing their business model for the public market.

Some of the challenges with a number of these businesses are that their business model is being debated publicly. One of the big reasons why a number of companies haven’t gone public yet is because they’re still developing that business model.

That luxury of time for some companies is certainly valuable, but tech is only 30%-40% of the IPO calendar in any one year. There are clearly a number of other sectors that have done very well in the public markets, and we’ve also started seeing some real life since last year’s presidential election. Financials, industrials, and other sectors have been big beneficiaries. And investors in those sectors have done well investing in those IPOs.

IFR: Doug, I think you have a strong view on whether the tech IPO market is broken, don’t you?

Doug Baird: I do. I will preface it by saying not one of my colleagues, or competitors, or clients agrees with any of this, so I’ll get way out in front of it.

My experience is that companies go public when they have to, not when they want to. In the old days I had an idea, I’d pass the hat at Thanksgiving, do a seed round to see if it was a good idea, and then I’d do a Series A to build a product. Then I’d do a Series B to bring it to market, and then I went public.

Uber has done a Series H, Airbnb a Series F, so companies have built out and scaled in the private markets. That obviates the need to go public. We can have an interesting conversation about whether it’s in the national interest for these businesses to be public. It’s my money that’s invested in all these companies. It’s my mum’s money through crossover mutual fund companies, but none of that’s happening in a public domain. Over cheeseburgers and beers later, we can talk about whether that’s actually a good thing or not.

Companies, as mentioned earlier, sort of rightly recoil at the thought of being held accountable. Craig, my middle son who just graduated from college, said to me: “You know, Dad, college would be awesome if it wasn’t for those tests and having to take courses.”

Anybody would dodge the accountability if they were able. But it’s in fact the accountability that makes the market awesome and in theory should be driving down the cost of capital.

In 1999, there were 200 tech companies that went public in the United States. In 2000, there were 150 – and then, the market blew up after the first quarter. That was just 90 days’ worth of action. Now, 2012, 2013, 2014, there’s 40 tech IPOs and everybody’s super jacked. In fact it’s really still a trickle.

IPOs are a financing transaction. At the core of it, it’s a financing. It’s really not about brand building. Yes, it’s an event and I get to be on TV and all that. That’s like, “Whatever”, but at the core here you’ve got a company that is in a financing moment.

If the cost of that capital is price at US$20, open at US$40, over 20 years people will be conditioned to avoid that financing moment. If, in fact, that’s how much it costs to be public, people will simply not do it. I think that’s very much at the core of what the issue is.

A non-tech company in the US, we can price that on the screws: An average 6%–7% opening trade versus pricing. The numbers triple for a tech business. If you’re a consumer-branded internet company, it’s like 70%. It’s like it’s out of control, so rational people are just not doing it.

We’re not around Spotify, but if I read the headlines there is at least one management team who is saying, “Yes, I’m just not going to. I don’t need to endure this deluded moment to create liquidity for myself.” When I think about that, to me it’s always about how much does it cost. It’s a financial transaction. If your IPO isn’t exploring price, then what are you doing?

A 100% one-on-one hit rate doesn’t mean you’ve got a great analyst, a great salesforce, and a smart ECM guy; it just means your range was too low. If people are resisting based on value, you’re not identifying the value of the business and then you’re not really positioning that company. You’re not really talking about its opportunities, strengths, weaknesses, and threats. You’re just hanging a piece of salami out there at half its value.

IFR: There is accountability that comes with being public, whereas we have seen some high profile cultural problems at big private companies like Uber and SoFi. Carolyn could you elaborate on the corporate governance benefits of being a public company.

Carolyn Saacke: I can’t comment on any one company in particular, obviously, but there is that accountability – and it’s been mentioned before – when you’re a public company. There’s a certain sense of discipline that you have to have because you’re in the public light.

When companies are waiting until they have US$50bn in value [before going public], you kind of wonder sometimes where some of the bodies are buried, where the skeletons in the closet are, and how many closets there are. When you’re a public company, you have a bit of cash to maybe fund some of the hires that you need to make for compliance, and for HR, and for all of those things that maybe when you’re growing really, really quickly, you just don’t have the time for or the money for. You can say, “I can do that later, it’s not really important now”.

It is important. Certainly you don’t want bad news to come out while you’re on the verge of an IPO, but that accountability is really, really important. It will be very interesting over the next year or so to see how many of those larger unicorns find alternative methods to go public.

IFR: Craig, We talked before a little bit about Blue Apron’s IPO in June. One of the issues there was that that was a down-round IPO, and there’s always a lot of focus on that in the media. What are some of the issues that arise when you have a down-round and how does that affect the price discovery process?

Craig DeDomenico: We had some other bookrun IPOs that went up this year, but we won’t talk about those! It goes a little bit to Doug’s point. Obviously, about two-thirds of the IPO market is coming out of PE firms or VCs, and this year you could probably split that in half.

Ultimately, there’s no doubt that, where the last private round was for Blue Apron, it was approximately flat, to where they ultimately IPO’d. We all know after a quarter or so how that stock has performed with Amazon and other news in the public domain. [Amazon’s US$13.6bn purchase of Whole Foods Market was announced just prior to Blue Apron’s IPO launch.] In reality, as we brought that deal to market and we pitched it, it was in the back of our mind, but we didn’t see that.

Public institutions were hanging their hat on where the last private round was priced in 2015 as they thought about Blue Apron as a viable public company. But obviously for the people in the boardroom that were making the decision whether to sell and whether now is the right time, clearly that’s important.

We weren’t involved with the Canada Goose IPO, but I know that priced at a pretty big discount to their last private round and it has traded fantastic.

If you take a longer-term view and you realise you’re selling only a percentage of your float – and ultimately the access to equity and everything that comes with that is going to help grow the business – then it can matter. But I think the institutions that we want to see in our IPO books and in the top 10 holders lists I don’t think are going to look at where the 2014 or 2015 round got done and hang their hat on that as the right value for the company, or feel like they got it cheap.

IFR: Anna, there are of course ratchets in place on these deals to limit dilution for private round investors. How do they work?

Anna Pinedo: Just to pick up on the last comment, there’s so much written about the last private round valuation, and so much of it is misrepresentative or just not a fair comparison, because people were comparing a preferred with liquidation preferences. Or maybe it’s a participating preferred. There are so many different ways these rounds are structured.

There are a bundle of rights that go with private round financings that bear no resemblance to buying common. That’s one point that is important for people to bear in mind and, if you were to adjust for a common stock valuation, how far off would you be? I don’t know.

Obviously, investors in late-stage rounds have become more aggressive about asking for protections in terms of IPO ratchets and M&A protection, in case it does come to pass that the IPO valuation doesn’t compensate them for the rate of return they had bargained for.

Of course, the function of the IPO ratchet can be very dilutive. Similarly, in M&A scenarios we’ve had a difficult time negotiating and dealing with some of those ratchets, so it is something to bear in mind as a company that’s raising money in one of these crossover rounds.

It’s clever to contemplate that in a direct-listing scenario a company cannot be subject to some of these IPO ratchets the way they’ve been written historically. Will that last? I don’t know. The way that most IPO ratchets are written is an underwritten public offering, and they don’t contemplate a direct listing, so is it too clever by half? Will all the lawyers catch on and rewrite the provisions? Probably, but there’s lots of interesting negotiating points on these transactions.

IFR: We’re lucky enough to have a buyside view here. Michael, how do you view unicorns when they go public? These are companies that have huge addressable markets and high growth, but there may be low barriers to entry and the threat of being disrupted themselves. How do you value them?

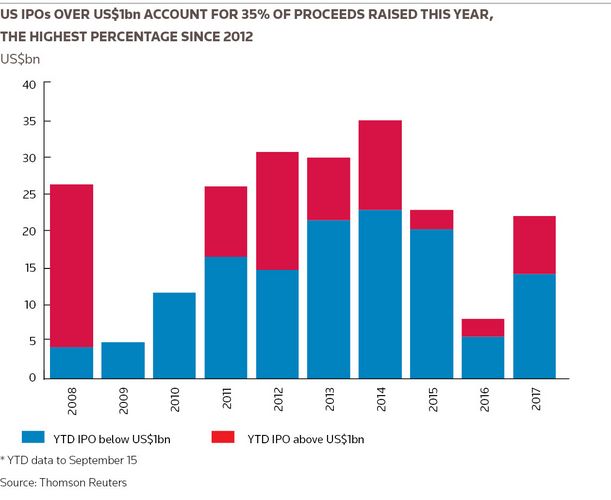

Michael Kuchmek: We look at them just like any normal company. The only difference is the valuation and how far along they are in their progression. When you’re looking at unicorns, there are as many public as there are private now if you define that as a US$1bn or higher valuation.

The first thing we assess is how easily a company could be displaced by someone like Amazon. How low are the barriers to entry? What is the branding? How sticky is the brand? How likely are they to be acquired in the future or put into one of the other companies looking to enter that field?

We really try to focus on whether we have the right metrics. That’s the one thing people don’t talk a lot about. We try to pretend that all the tech IPOs are the same, or maybe we should look at DAU, or MAU [Daily Active Users/Monthly Active Users], or whatever metric. You really have to ask: “What’s different about this business? Are these the right metrics? How do we view the milestones and progress?”, because that’s really how it will ultimately trade over time.

Even extremely successful IPOs like Facebook, it was viewed as a failure at the beginning, but it wasn’t; it was just the process of facilitation. We’ll see more of those, where these much larger companies that are not going to necessarily have the traditional plus 10%, 20%, 30%, or 40% first day pop, but they ultimately give you a lot more chance to benefit from value creation over the medium term.

Brett Paschke: If I could add just one thing on the unicorn topic. I’ve been fairly amazed how persistently this topic has been a factor in decision-making around whether a company should go public. Anna’s commentary around all the protections and the non-comparability of the private round versus the public round, that’s real and it’s true.

The other thing I’d throw in there is those [private] rounds are often for 5% of the equity and they’re trying to extrapolate the value across 100% of the company, and without the protections. I saw at least one academic study that says the differential, once you adjust for that, is about 35% in terms of the valuation.

I was involved with a panel through the National Venture Capital Association a few months ago. They were actually presenting that information to the audience of venture capitalists, almost as a way of saying: “Listen, we have to get over this concept that we can’t go out at a lower common round than these private rounds. Those valuations aren’t comparable. Here’s the difference.” It was almost trying to help get them over that US$1bn threshold. It’s not going to ruin your fundraising ability going forward, and all those sorts of things, but it has really persisted.

A lot of Doug’s commentary is absolutely the viewpoint of people, particularly in the Valley or venture-backed businesses. It’s put a definite dampener on the market. I’m hoping people get more educated on this, even the press. It’s helpful if, when talking about unicorns, we talk about the different structures, valuations, minority decisions, and not hold them out as failures for having gone public at what ostensibly looks like a lower value.

Pawan Passi: Notwithstanding the different pools of capital, I think the sheer number of investors that are now able to invest in IPOs versus private rounds does give greater transparency and, therefore, greater transparency in helping set value.

I would certainly say that the IPO part of a company’s life is still going to be critical, whether or not a company decides to be private for three years, five years, or eight years. I don’t think the IPO in the most traditional sense is anything remotely dead, but I do think it goes back to the point: “How do you want to evolve your business?” And evolving that business in public eyes versus private eyes.

Mike mentioned Facebook as a good example. If you think about the most important stocks in the US – certainly in the last half a decade, certainly in the last couple of years – Facebook, or ‘FANG’ as a concept, clearly the first of that is Facebook. [FANG is the acronym for the four listed US tech giants: Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google (Alphabet).]What we’re talking about with Facebook is US$500bn of market value. That’s greater than most of the private companies that we’re discussing here, combined.

It’s very easy in a vacuum of a year, or any given year, to get overly focused around what is happening with unicorns in the private sphere. If you take a step back, many of these companies, once they’ve gone public, have been big sources of growth for investors. I don’t think that will change.

The ability for people to put money to work in a public setting where they can get out immediately, should they wish to, I think will always still be valuable to investors versus owning a private security that, even in the best cases, the transparency of what is a fair price is going to be challenged.

To see the digital version of this roundtable, please click here

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email gloria.balbastro@tr.com