IFR: Without focusing too much on unicorns, one thing we often debate is the significance of multiple classes of voting shares. Index providers are now saying that companies won’t be able to join indexes if they have multiple classes of voting shares. Mike, what impact do you see that having on the tech IPO market?

Michael Kuchmek: I guess my view on different classes of voting shares is, personally, as an investor, it doesn’t really matter so much. When you’re going in and you’re investing, you’re investing alongside either the founders or the management, and you pick them for that reason. Especially early on in a capital formation process, you’re buying into the CEO’s vision, you’re buying into the business model, how they’ve progressed, and how they view things.

Would you not invest in the Under Armour IPO just because it has different classes of shares? No, you wouldn’t. Obviously, if we had the choice, you would want to have the voting rights and everything else, but I don’t think it’s a deal killer, and I don’t think it will be in the future. Each situation is its own unique circumstance, and, as long as the business model is there, as long as the management has a good vision and a good plan, that there will be capital provided for it.

Pawan Passi: Again it’ll come down to the individual managers of that business. At various points in time, the market may put a discount on that manager because they have managed the business irresponsibly. And yet there’s no way to effect change, given the voting structure. Then other times people want to be behind that manager because they have disrupted the industry in such a way that clearly they are the reason why you own that stock or that company.

Again it speaks to the value of a public market, where you can decide on any given day what you want to ascribe value to. Some index providers and some of the passive investors have made a delineation. These things change as well with sentiment. To have established a rule at this point, who knows if that doesn’t change at some future point. We’ve seen that same thing with domiciling, and my sense is that this is just another thing that people will debate and will likely go back and forth on.

IFR: Carolyn, what role do the exchanges play in terms of allowing or not allowing multi-class share voting structures? I’m thinking about exchange arbitrage and whether exchanges play one against the other.

Carolyn Saacke: Rules are very, very similar between the exchanges. That’s done on purpose by the SEC because they don’t want arbitrage between the exchanges, based on corporate governance rules. We should all have great corporate governance. We all follow Sarbanes-Oxley and everything else, and so that really shouldn’t be at play.

From our perspective, we allow multiple classes of voting shares. It’s fully disclosed. We make sure that the boards of the companies are following our rules. All of our rules are also governed by the SEC, so they do look at what we do anytime we want to change something. They compare us to our competition. They compare us to what we have done previously.

We can do a lot of things, but what we can’t do is really loosen our rules or our regulations very easily. That’s frowned upon. So if there are things that we can do to enhance regulation, we certainly will. If there are things that are out there in the marketplace that the market wants that could be innovative, we’ll look into changing our rules for those types of things.

IFR: Doug if we go back a minute to the issue of direct listings, is that a threat to traditional IPO underwriting?

Doug Baird: It could be. I personally think it’s a great idea and it will be interesting to see how it plays out. I’m sure the SEC is paying close attention to it in the case of the music-streaming business [Spotify], because it’s an important, well-known company that has the potential to be widely owned quickly. It does represent the possibility of solving this problem.

As we’ve talked about, companies go public, basically, for two reasons. One is they need money, and two is they want liquidity. Most of these unicorns are financed. The successful ones, particularly the larger software enterprise businesses, are already running at cash-flow positive, so they don’t really have funding needs, but they still need to get liquidity, largely for the people who work there.

Maybe there’s a way to split that baby where you can get legitimate liquidity on the New York Stock Exchange. It is never going to be as good on some private exchange. It is not ever going to happen. Trading stocks by appointment must cost more than having them trading at penny spreads. If I can get that liquidity and I don’t have to fake-raise money I don’t need, yes, smart people would pay pretty close attention to that.

Whether direct listings are a threat or not is a different question. Don’t worry about us [the banks]. We will figure out a way to get paid and provide service and value to buyers and sellers of equity. That’s not important. It’s whether or not this will serve the needs of issuers, their shareholders and employees, and it could happen.

Carolyn Saacke: Not speaking about any one company in particular, these are going to be done, if they are done, on a very limited basis, right? Just like you said, Doug, they have to have liquidity. There needs to be enough folks that actually want to sell shares and that are going to be ready to sell shares on day one. They have to have that price discovery process that we do at the NYSE – to be able to tell what that right price is – because there is no IPO pricing mechanism there. If you think about it from that perspective, yes, the banks need to be involved with that, because they are the ones that know how to value these companies.

It’s going to be done on a very, very limited basis. Not everyone can do it, and there are positives and there are negatives. Certainly if you’re not looking for another financing round, if you’re fine with the level of institutional ownership that you have at that particular time because you’re not broadening it during a direct listing, then you should consider it. It will be really interesting to see where this develops over the next couple of years, for sure.

IFR: Thank you. You’re not scared, Passi, about direct listings?

Pawan Passi: As you already said at the beginning, there are very few IPOs this year, so I’ve had to find an alternative means of making a living! But I do think the comments that have been made already are right. I think it’s going to be highly bespoke. Only so many companies are going to be able to do it.

In the same way that Google, when they went public, went public via Dutch auction, there haven’t been many other companies who’ve done Dutch auctions since. These things can be a once in a moment and it hasn’t changed the last 15 years of the business. Whoever wants to do this, I wish them all the best. But I’m not sure it’s going to largely change the rest of the business.

Craig DeDomenico: To a certain extent it’s all, to Doug’s point, driven by capital need. Clearly, they don’t need capital. They have an investor relations problem, which is they are going to have to communicate with the Street. It’s going to have to be a big enough branded company that we’re all going to care and do all the right things, in terms of research and making sure that story gets out in the right way.

When we think about companies that come out of bankruptcy reorganisations, many are OTC-listed and need to totally rebuild their shareholder base. There’s always a discussion around whether we just simply list on the stock exchange. Should they raise capital, even if they do not need to pay down debt, to generate enough trading liquidity? We’ve seen all versions of that. A lot of the large coal companies have just directly listed and let it play out, almost like an LP distribution. It could be sloppy early, but over time they’ll probably be okay.

It all goes back to Doug’s point on capital needs, to the extent we, as bankers, can convince a company that: “It’ll take you three months to get registered anyways. You have a need for capital. Let’s do it altogether in a re-IPO.” Clearly that’s the cleanest way to do it, but that’s maybe a shorter-term view and obviously a little bit selfish for everybody on this panel. But it’s not as if we don’t see this on a regular basis with a lot of companies coming out of a reorg. Think about the amount of energy companies that Doug’s pitching to take public. Many of them will just decide to directly list.

Doug Baird: I’d just add Time Warner Cable went public like that. That was instantaneously a large-cap company, with tons of liquidity and a fancy 13F filing. It happens. On the one hand, we’re acknowledging that these big companies are doing multiple private rounds, in many cases led by the very institutions that would be at the top of the [IPO] pot list.

A lot of people already own the stock, outside of employees, but there’s every reason to believe there’s a bid and offer tied to the market at a price. That’s the magic of what happens on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange every day. Can that happen without us systemically under-pricing an IPO the night before? I think it can. Again, time will tell.

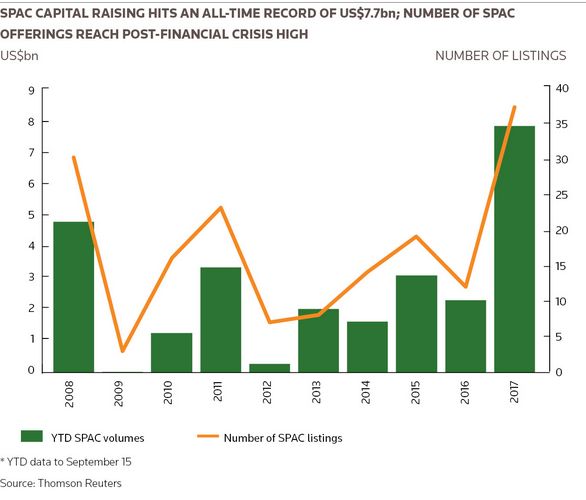

IFR: Carolyn, one of the positive developments this year has been the resurgence of SPACs. The NYSE has been open to listing them this year and there have been a lot of structural changes that have made SPACs more agreeable to investors. What was behind the NYSE’s decision?

Carolyn Saacke: Yes, it sounds like it was overnight, but it really took two years and nine rule changes with the SEC to be able to list SPACs again. They’d all been listed on the American Stock Exchange back in the day. We bought the American Stock Exchange in 2008 and then started to completely ignore the SPAC market.

But it has been different over the last few years. They’re much larger companies. There are better management teams that are running these SPACs. They have done acquisitions before, so SPAC IPOs are actually resulting in business combinations. These business combinations are resulting in companies that should be NYSE-listed.

The most famous one recently in terms of size was Hostess Brands. That’s a company that we would love to have listed on the New York Stock Exchange. [Hostess listed on Nasdaq]. Because of that, we really started to focus on what do we need to change our rules to allow for those companies and SPACs to list on the NYSE.

We basically looked at all of the structures that were out there and made sure that our rules fit into the market, changed our fees, changed our shareholder requirements, and just again made them in line with what the market was demanding.

We were able to start listing them earlier this year. The last rule change was in June, and our first SPAC for a long time was TPG Pace Energy. It raised US$600m on the NYSE in May. We’ve now listed five. You just saw a really interesting one, Social Capital Hedosophia, which raised US$600m. Its goal is to go out and buy tech unicorns. It’s a very good conversation for the types of things that we’re talking about today.

Social Capital got a lot of buzz – the most buzz that any SPAC has ever gotten in media history, I think because it had the word ‘unicorn’ in it.

SPACs are just something that we’re going to see a lot more of. Again what these SPACs are doing is they’re raising money in the public markets. You’re buying into your faith in the management team to buy a company within typically a two-year timeframe and then bring that company public.

Most of these targets are private companies. We did see CF Corp, which is a combination of Chinh Chu [formerly] from Blackstone and other executives, buy Fidelity National Financial, which was publicly traded on the NYSE. That was a little bit different in terms of the type of company that CF was planning to acquire.

Some of the SPACs that are going into the market nowadays are still very general in terms of the industries that they are focused on.

A lot of them are very specific. We’re seeing a lot focused on energy, bringing in some very important energy executives that have done this in the past to lead them. As I mentioned, Social Capital is looking at some tech companies. Others are focused on distressed industrials. Some are looking at just general things.

What we’re also finding is that as these are getting a little bit more accepted in the market – and I would love to hear from a buyside perspective – you’re also seeing traditional institutional investors buying in at the IPO. That’s also driving the popularity of these particular types of transactions over the last few months.

IFR: Yes, that’s an excellent transition because we were really wondering.

Michael, what is your investment approach to SPACs given they differ from traditional IPOs?

Michael Kuchmek: We have a separate sleeve as part of our strategy that invests just in SPACs, and really we’ve seen it change completely since SPACs were created. Before, they were a very taboo area, and they were a lot smaller, raising US$150m or less. Nowadays, the majority of SPACs you’re seeing are raising US$400m or more, and up to US$1bn. Above US$1bn it’s a little bit hard with the promote structure and what they can acquire to make it work, but still US$400m-$1bn is a pretty good size to start off with.

The comment about the sponsors being higher quality is absolutely true. We look at it as institutionalisation of capital markets as a whole. Every buyside firm now typically has a person that does capital markets. The sponsors themselves are looking, whether it’s having an external manager for a commercial mortgage REIT, or a private equity fund. They are asking themselves: Do they have each of the product sets?

We really see the SPAC as just a product extension. Perhaps it’s the customisation that means they’re able to [structure an acquisition] with better tax planning for a family that is selling a business, whether it’s them selling energy assets, whether it’s a company that did a lot of acquisitions recently and would like an earn-out.

There are lots of different ways you can combine them, so we think that SPACs are here to stay, that they’ve been institutionalised and that we are going to see more of these. You’re going to see repeat sponsors bringing them.

The second piece that is very important is that the timeline to completion has compressed dramatically. Before, it used to take 12-24 months to get an acquisition done. Now, the average deal is getting done in six months because these are professionals that have pipelines, that have all the relationships. And so the time to facilitate is actually a lot shorter.

In terms of the evolution of the product, you’re seeing different buyers in SPACs. Before, it started off mostly as a merger arb product. You would have one warrant [attached to each share]. That has now changed, largely to one-third of a warrant, or one-half at best, which is what the market dictates now. And you’re seeing a lot more fundamental guys [investing in SPACs].

It’s a product where a hedge fund or an alternative asset manager can almost leapfrog long-onlys on allocations. Hedge funds have a broader mandate in what we purchase, and the style of the product, etc.

Back-end [acquisition] versus initial [investing at the IPO] is another area where we have seen change. We like initial because you’re basically long a free call option, in essence, with a proven management team. If any one of us said: “Hey, Chinh Chu is going to go buy something; you can get a free call option on it”, we would all take it.

On the back-end we look at them as well, but we would look at the back-end more like a traditional IPO, which is you’re losing that put-back option if you don’t like the asset.

Being a consistent investor in the product gets you that look on the back-end to maybe see the acquisition, to get wall-crossed. We were just wall-crossed on one yesterday. That gives you a chance to be one of 20 or 30 investors that really understand the target acquisition and gets a leg up.

To see the digital version of this roundtable, please click here

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email gloria.balbastro@tr.com