IFR: Given the dilution that results from founder shares, can SPACs really compete for assets when they come up against strategic buyers?

Doug Baird: That promote can be moved around, so there’s value there that can be ultimately split between the buyer and the seller. There is a way for the market and the acquisition process to adjudicate where that promote needs to go and how that impacts value.

What I’d add about SPACs is to me it’s another flavour of arbitrage for people who are trying to rewire the go-public process. The way I explain it to clients is that for a regular IPO you do a roadshow and then you price a deal. In a SPAC, you price the deal and then you do the roadshow.

You have much more latitude in terms of what you can disclose, and you can talk about forecasts and cost synergies. It’s a much more open, fluid, adult conversation about what the opportunity is here around a specific price.

Ironically, it turns out to be a more civilised way to, again, adjudicate the cost of capital in a financing moment. Part of that is, again, the ability to move that dilutive nut around. Your instincts, by the way, are genius because it’s an issue. There’s no doubt. The thing about the structure of the SPAC is it needs to be done in such a way that that dilution is accommodated by the sponsor.

Craig DeDomenico: To Doug’s point, obviously none of these back-ends are getting done at a premium to a traditional IPO valuation. Generally, we’re sort of giving them IPO advice, but, to Doug’s point, our ability to portray a story publicly through the merger proxy provides a lot of flexibility.

Some companies that were in backlog as IPOs have decided to go this route. Rarely do you get to the finish line, unless it’s a very cheap deal where that promote isn’t manipulated or moved around to make it a more palatable solution, because guys like Mike get brought over the wall and it’s the first thing they ask.

Ultimately, it’s an auction. If the auction is way oversubscribed, they keep all the promote and they’ve found a really good deal.

The other thing on the front-end IPO, there’s no doubt there’s more enthusiasm than ever from investors trying to create an asset class. I would say, even with the merger arb and the hedge fund community sometimes being the mafia for this product, they are very focused on institutionalising it and trying to get more outrights in. Therefore, order books are getting broader, and it’s helping.

It’s also helping to give confidence that the back-end process will be less painful for the promoters who, effectively, put some of that at-risk capital at work. But there’s no doubt that every bank is now starting to include SPACs as a potential merger partner, whereas three years ago there’s no way that SPACs would be part of an M&A discussion.

We’ll see. In a rising interest rate environment, or where funds get overinvested or have less capital to spend, we’ll see if it’s a bull market product or not, but it’s definitely more institutionalised than it’s ever been.

IFR: Anna, what is your outlook for ECM, not just in terms of activity levels but in terms of trends?

Anna Pinedo: Probably the biggest thing is the different dynamics that are shaping the IPO market. We’ve transitioned to a point where almost every public offering we do is wall-crossed, has a confidential marketing period, or is an accelerated deal.

The difference when I started practising 25 years ago was that you had a public follow-on. Now virtually no follow-on is truly public. That seems like a change that’s going to persist, and it’s also a change that has been made that’s probably going to be accentuated by the SEC’s recent policy that in your first 12 months of existence you can do a confidential submission.

Brett Paschke: I would absolutely agree that the changing process of raising capital has affected the participants. It’s skewed the data on what percent of follow-on offerings of existing public companies actually were fully marketed. This year so far it’s been 13%. If you look back six or seven years, that would have been 75%. So it’s skewed very much towards confidentially marketed, wall-cross, or a true overnight, where it’s announced at the close at 4pm. The markets are closed, and it’s priced that evening or the morning before the market opens again.

That has a lot of implications in who can participate. We didn’t talk as much about bought deals tonight, but that’s been very much driving that. Doug said he wasn’t worried about his side of the table getting paid. It does have some implications when the large balance sheet-oriented firms are buying those deals in non-economic ways, under the assumption that, if they’re doing a good favour for a large private equity firm, they’ll be compensated in ways other than that deal, be it the lending on their next buyout or a large role on the next IPO.

They can literally buy them in non-economic ways, which is good for the seller and clearly makes a lot of sense as to why they’d want to do that. But it does sort of produce in some ways, on an individual deal-by-deal basis, a little bit of unnatural pricing.

That then ripples through the ability for the non-balance-sheet banks to continue to pay research analysts. Some of those are providing some of the fundamental research that the buyside does value.

The second thing we didn’t talk about that’s a future issue is the passive versus active investing debate and how that ripples through the ecosystem. It pushes down on the value of sellside research and the ability to pay sellside research analysts.

I think people have heard this stat, but it still bears repeating because it’s amazing: More inflows went into Vanguard last year – Vanguard alone – than all active managers combined, which is pretty amazing. Again that ripples a lot around the ecosystem of the whole sellside dynamic and what the buyside uses the sellside for.

This combination of factors – fast capital raising, non-economic bought deals, and active versus passive – definitely impacts the ecosystem.

IFR: Carolyn, you have some visibility into the IPO backlog. What do you see ahead?

Carolyn Saacke: Yes, it’s a heavy backlog. Companies just aren’t listing right now. The pipeline this fall looks okay. We’re comparing it to what we have been seeing last year, so it does look okay. We can’t really compare it to earlier years. We can’t really even compare it to 2014. We would love to. It’s a slower year, for sure.

These are great companies, though, that are going public. We’re going to see a lot of international firms, and quite large ones, over the next few weeks, hopefully. They’re already out there in the market and on the road, so hopefully they’ll all price well. We’re seeing a lot from that perspective.

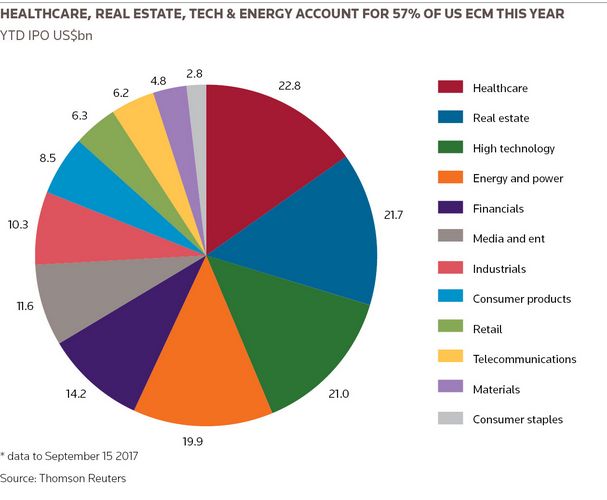

Some industries that we were expecting a lot from this year we’re not seeing as much from, but it’s pretty diversified in terms of the success of those companies that we’ve been seeing. It’s not all about tech. As you mentioned, tech is like 30%-40%.

IFR: Passi, you have a fairly bullish view about the outlook over the next few years, in part due to the potential for some mega-IPOs. Can you elaborate on that?

Pawan Passi: One of the reasons why IPO volumes have been somewhat subdued over the last two years is that we haven’t had one of those mega-IPOs that, frankly, by coincidence or maybe by a function of business cycle, have punctuated the market every two years.

Whether it’s Alibaba, or then going back to Facebook, GM and Visa, at various points, almost every two years, you’ve had a number of very large companies that, on a dollar value basis, have contributed to the IPO volume.

Maybe that’s because of the private capital theme, efficiency of markets in the case of other companies that may go for direct listing. But for whatever reason, we obviously haven’t had that.

I do think it is inevitable that there will be some. Whether it’s foreign companies choosing to list here in the US or whether it is, indeed, some of these private companies going public, it’s a matter of time, whether that’s in 2018 or 2019.

As for SPACs, whether it’s a bull market product or not, we don’t need to debate that. But effectively it’s a reflection of people’s view about how long they want to be private. Maybe another way of saying what Doug was saying is that every IPO is a failed M&A process. On one end of the spectrum you have the IPO, where you’re effectively taking two years of market risk as you get out of that position, and on the other you have an M&A sale. It feels like we’re back somewhere in between the two.

I think we are at some inflection point in the second half of the cycle. Whether it’s the end of that second half or whether the beginning of the second half or somewhere in between, it’s clear that we’re in something of an evolution.

The debates about whether or not I want to go at a lower price relative to my prior round is very much like selling your house below where you bought it. Ultimately, it sucks to sell your house below where you bought it, but, if you need the money, you’ll go. So there’s some element of that; these things just take time to play out.

We haven’t talked about how the consumer space has evolved in front of our eyes over the last five years. You’re seeing a number of assets in the consumer space look to go public. We can keep going. Industrials are clear beneficiaries of potential infrastructure spending.

Clearly, there are a number of trends that are evolving to the positive and will ultimately lead to IPOs. Whether these companies are going to go public in September, whether they’re going to go public by December, I don’t know. But I do think there are a lot of very positive things happening that mean we can be bullish about ECM.

IFR: Doug, what about Latin America? ECM activity looks to be heating up there.

Doug Baird: Yes, that is definitely upon us. It’s largely Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, and it’s all built on macroeconomic repair and policy in those countries. Their currencies have stabilised, their sovereign borrowing levels have come back down to earth. In an environment where the perceived risk of investing in those regions has declined, you have a bunch of interesting businesses seizing that opportunity to get themselves financed.

What’s doubly interesting about it is, this time it’s internet businesses, it’s consumer packaged food companies, and transportation businesses. It’s not just natural resources or metals and mining kinds of companies.

It’s a much broader snapshot of the economies in those parts of the world. They’re financing in dollars and local currency. They’re listing here and they’re listing in their home countries. It’s become very vibrant relatively quickly, in a good way.

IFR: We’ll open it up to our audience for questions.

Audience member: What percentage of index funds participate in ECM deals these days?

Pawan Passi: I would say there’s a lot said of how important they are in the secondary market. By and large it’s still very much a minority in terms of the actual bookbuild process.

As you think about where the US could go as it relates to index versus other parts of the world – Japan most notably, where 70% of the market is index – I don’t think it’s having a meaningful impact on the bookbuild process. But what I would say is that it is obviously making understanding how stocks trade more challenging.

Maybe ‘challenging’ is the wrong word, but passive/quant dynamics are playing a role in the first-day trading of deals in a way that is truly unseen. That’s making things a challenge.

I wouldn’t say it’s necessarily changing the demand. But certainly as we think about the aftermarket, it’s out there and it’s different than it has been in several years prior.

Audience member: We haven’t really talked about the cash equities business. It’s really undergone some massive changes. Even the sales force that you have and what they do day-to-day is maybe changing and evolving into kind of a non-deal roadshow concierge type of service.

How does that make your jobs challenging/easier? How do you see that in your syndication role, your relationships with the buyside, this evolution of index, passive/active? There’s a confluence here that maybe makes it more challenging or not in terms of distribution, and colour, and getting the pricing right.

Pawan Passi: I would say it’s just evolved. In the same way that I think there are some significant positives around the JOBS Act – particularly it was discussed around life sciences – it does mean that companies are meeting with investors sooner. The sales force’s involvement in an IPO can extend years prior. That was different prior to the JOBS Act. That’s just one example.

I do think the point Mike made around the buyside seeing the capital markets as an asset class may be a reflection of where we are in the cycle. It means that the sales and the cash equity role has been transformed.

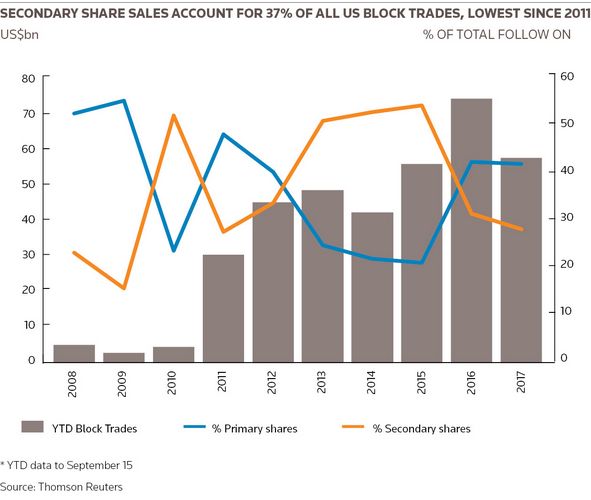

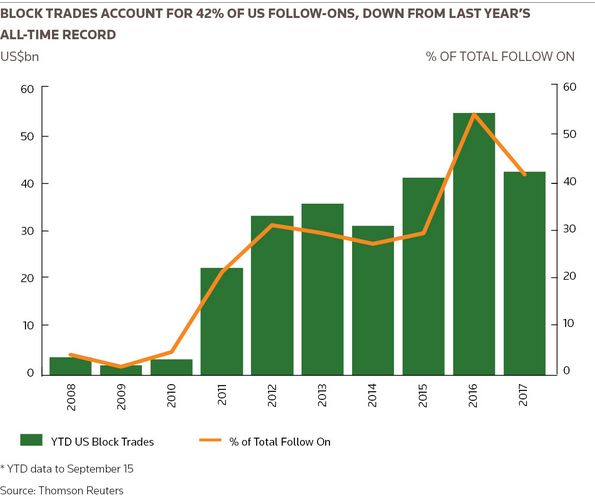

Equally, even though we have progressed since the crisis, secondary liquidity has dried up and what you’ve seen is a huge surge in block trading among institutions. Whether that’s taking place with direct pools of capital or whether it’s taking place through trading desks at firms such as ours, that has changed, again, the role of the cash equities business.

We obviously haven’t spent time talking about research, and how that’s evolving too and is going to change. I don’t think it’s made the job any less challenging. I don’t think it’s necessarily brought more challenges. I think it’s just some of these products are now requiring longer lead time, or specific market access in the case of block trades at a point in time. That’s different from passively trading orders over a desk.

Audience member: Companies no longer split their stocks. You have an equity compensation system that’s based on the number of shares traded. Has anyone ever thought about changing that? All these tech companies never split, so not only do you have declining volumes because of more indexing and some of the other things that are going on, but there are fewer shares traded, just because companies don’t split their stocks anymore.

Carolyn Saacke: What’s interesting is we actually have more conversations, probably, going the other way, primarily because our fees are based on shares issued and outstanding.

Sometimes companies, as their stock price is going down, talk about doing reverse splits in order to reduce some of the expense of listing on an exchange. But certainly that hasn’t been a conversation that we’ve been actively having with folks.

We certainly can do that at any time if companies are interested in doing it. I’d be interested in what advice the bankers have been giving their companies and whether or not that’s something that has been in discussion.

We’re trying to do everything that we actively can to increase volumes of trading, especially on exchanges, because there is more transparency than in some of the other markets.

Audience member: We touched upon it a couple of times briefly, but how do you guys see everything that is happening in research at the moment affecting the equity capital markets business and the way you do business, if at all?

Doug Baird: It obviously goes all the way back to the global settlement, right? There was a huge concerted effort, with a very comprehensive regulatory regime, to try to remove sellside research from the new issue process. It remains a very tortured relationship. There are lots of walls, and we can’t pitch together. It’s a very different process than it was even 10 years ago.

It gets back to an earlier question about the change in the cash equities platform and the role it plays in new issues. It’s all part and parcel of the reality now that in executing any trade – an IPO, a follow-on, converts, block trades – the direct dialogue between Passi, his desk, my guys, and my desk directly with accounts, is very high.

All of the large mutual fund complexes and hedge funds have their own syndicate people, so there’s a very vibrant dialogue that’s now directly from underwriting desk to investor. That bypasses a salesman, a coverage trader, and in many cases a research analyst.

I don’t know if I’ve directly answered the question or not. Research is vital. It’s a source of intellectual capital that is at the core of any IPO, but they’re running alongside us.

Craig DeDomenico: From a smaller platform’s perspective, we’re trying to look 24 months forward, and really think about the analysts that we have in the seats, and trying as originators, obviously with the compliance walls in place, to understand what their vision is. What they want to be focused on and covering? What their next white paper is? That we are chasing the right things.

Our ability to coordinate and make sure that it’s as efficient as possible, given we’re in a world of fewer bodies, fewer analysts, lower fees on the sales and trading side. That’s really how we think the firm can move forward.

Clearly, the analyst’s infatuation with a given sector or white paper means he’s going to be out talking with those companies. That means that there’s already going to be a branding exercise. Clearly for us that’s an important piece of it.

We definitely have to be 12 months earlier than we used to be as we think about where things are headed, and our ability to coordinate with fewer bodies and the environment that we’re in from a compliance and regulatory perspective. But origination is critical. As Passi said, our ability to build backlogs and bring new-issue business has become more important to the firm, not less.

Pawan Passi: Maybe just to add on the research point. If you look at one of the other evolutions post-crisis, it’s been the proliferation of bookrunners on deals. Gone is the day that you’d have one bookrunner take a company public. One of the reasons for that is that the companies want to have as many research analysts as possible, without having to pay for it.

I do think we’re just in an environment where people have struggled for performance, whether you’re an active manager or a passive manager, whether you’re a long/short fund because shorts haven’t worked or longs haven’t worked at different points.

Whatever it may be, people have struggled for performance and so naturally one of the things you’re going to focus on when you’re struggling to grow is how do you cut costs.

The sponsors behind some of these private companies are no different, but certainly the conversations that you have in management teams around research is never: “How can I get less?” It’s never: “I want fewer co-managers because I don’t want more research.” In fact, private companies are the one place where the research and having research analysts write about a company that isn’t well understood by the market, relative to publicly traded companies, has never been more critical.

If you think about a world where there’s so much information, getting your story told daily by research analysts is a critical piece of it. I think we’re just at an impasse where people are trying to pay less for a service, as little as possible. But I do think it’s still a critical part of our jobs and taking companies public. The research part will be here to stay.

Audience member: Can you guys just talk a little bit about the block trade business. It used to be a company would go public and then do a couple of follow-ons that are marketed. Yes, you have the execution risk of being in the market. Block trades obviously minimise that, but at the same time a marketed deal as a first/second follow-on winds up usually expanding the shareholder base.

It’s a competitive environment and process, obviously. I get why. If Blackstone calls the banks at 3:50pm and says they want to put up a US$1bn trade, how do you assess what are the good opportunities to bid on, and not wind up bidding too aggressively, and at the same time not being wide every time and then the sponsor just giving it to the next firm?

Pawan Passi: There is a chance that we saw something of a tipping point last year in terms of how quickly companies were turning to block trades. There have been some really good data points that will only incentivise more companies to do [a block] as a first, or second, or third, or fourth form of liquidation.

It speaks to the efficiency of markets. If this panel has agreed on something, it’s probably that markets have become more efficient, and there are tools to make it even more efficient still. What’s to say that you need a second follow-on to tell the story to the mutual fund?

Not if they already have someone like Mike sitting in that seat, assessing and evaluating that company, having looked at it at IPO, looked at it at the first follow-on. Why does he need to see them a second, or third, or fifth time if, in fact, they were beneficiaries of the JOBS Act?

It’s just the efficiency of markets that have made these companies better understood than in prior years. There’s also a laser focus on these opportunities that there probably hasn’t been. Maybe that’s because the traditional trading desk, the way that orders are worked in the most traditional sense has changed such that this has been the way to deliver alpha into those organisations.

The biggest challenge we have, without giving away if there is a secret sauce, the biggest challenge we have is trying to understand what is in the price and what isn’t. People will say: “Discounts have got really tight.” But actually maybe the right way to look at it is the three-months in and the one day out, or the two weeks into the lock-up expiry and the one day out.

News sources like Thomson Reuters will regularly send out information on the next lock-ups to come off. If everybody is so fixated on it, what is to say that a 3% discount last year isn’t 1% this year? That’s the challenge that we face. Markets have become so efficient that a lot of this stuff is in the price, and it’s now trying to navigate around it.

Doug Baird: I’d add, too, that actually [the rise of block trading] is a reasonably rational thing, as nuts as it may appear on occasion. As Passi pointed out, last year there were a lot of blocks. It was a tough first half. There was a lot of volatility, and a lot of market uncertainty.

In environments like that, a rational issuer or sponsor will intelligently slide that execution risk to us and let us manage that in more bullish environments. With less volatility,like now, companies are trading just fine over a marketing period, so they will then retract that risk from us, and they will keep it themselves because they expect things to work out better. The markets are very liquid. Companies are talking to Fidelity, and T Rowe Price, and Wellington years before they go public.

LBO’d companies were once public already, so people know these businesses, and management teams’ stories. There’s lots of interaction at conferences.

It’s just that in many instances flying to Boston and sitting down across a table from people who have owned the stock for eight years doesn’t really deliver a lot of value. In those instances, a sponsor will pick a small number of banks that they think know the stock well and will go from there.

Nobody wants a block to go badly, including the issuer. Nobody‘s trying to pick anybody else off in that process. Our advice to issuers is, if there’s some new fundamental development nobody knows about, some new acquisition, some new manager, some new product, if there’s something new to talk about: “Let’s go talk about it”.

If we’re just trying to get liquidity on the back of a quarter for a well-owned, seasoned stock then, yes, the liquidity and sophistication of the institutional markets allow that transaction to happen on the phone.

IFR: And how does the buyside approach blocks, Mike, because not all of them work out.

Michael Kuchmek: We look at blocks more as just where we are in the cycle. Where are we at with the amount of easy money and the lack of volatility? While I understand Doug’s point about why a sponsor might want to offset that volatility, I would say these are very shallow bouts of volatility.

The past several years we haven’t had anything of several days or weeks with a stretch where investors are really at the mercy of the markets. The whole market has had a backstop from the Fed, and central banks, and their easy-money policies.

That’s why bid-ask spreads are a little bit narrower, because we haven’t had 4% or 5% corrections in the market. We haven’t had huge amounts of volatility. You would think US Foods was a debacle of a block [US Foods priced a block during the week of the roundtable.] It’s down 1%. It’s natural. They can go down. Things can go down.

One of the things that blocks do is make you make a decision in a quicker timeframe. Whereas normally on a marketed deal you have one or two days to do the work or do everything, if you’re a buyside syndicate and you work with other PMs, you have to make sure they’re aware of the timing, what could be out there, have a fundamental view, be able to react quickly, and make sure everyone is on the same page and have your work done ahead of time. Reverse inquiry has become very big [in determining the timing of blocks]. Make sure you know your levels and where you care.

I would say, compared to a marketed deal, on a block make sure you understand the different levels of outcomes. For me, a lot of times that means we’ll buy half to three-quarters on the deal, the other one-quarter to half in the aftermarket in case there are some loose ends that get out early. But ultimately we view it as just another type of trading vehicle. It’s fine, as long as you have realistic expectations going in, know what you’re paying for and how you think it will trade in the aftermarket.

IFR: Thank you so much to our panellists for those insights and thanks everybody for attending.

To see the digital version of this roundtable, please click here

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email gloria.balbastro@tr.com