Italy is fast running out of options to fill a potential €40bn capital hole in its banking system, leaving Rome with little choice but to launch a full-on government rescue – and plunging it into an inevitable conflict with the European Union.

Private investors have already demonstrated their unwillingness to provide sufficient fresh capital for struggling Italian banks, with Veneto Banca and Banca Popolare di Vicenza both failing to sell even a fraction of new shares on offer to private backers over recent weeks.

The botched sales forced Veneto and Vicenza to turn to industry-backed rescue fund Atlante, depleting its resources and leaving the fund with just €475m to recapitalise all the other banks in the country, a tiny fraction of what could be needed.

At the same time, Rome is reluctant to obey the EU-wide bail-in rules that it helped create for fear of imposing losses on retail bondholders. A bail-in of retail bonds could unleash a political backlash against Prime Minister Matteo Renzi and even against the EU itself.

“A state bailout is the only answer,” said one capital advisory banker who has worked closely with Italian banks and officials. “The banks have exhausted private capital, and bail-in isn’t going to work. There is no other real option.”

The urgency has its roots in European Banking Authority stress tests due to be published on July 29. The tests are expected to highlight a €40bn capital hole under an adverse economic scenario, and Rome is keen to have a plan to reassure markets and depositors.

“A state bailout is the only answer”

At the same time, the European Central Bank has been upping pressure on Italian banks to resolve their non-performing exposures (or NPEs), which have quadrupled over the last eight years to €340bn – equivalent to about one in every seven euros they have lent out. Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena, perhaps the bank most in the spotlight, has been told to reduce its bad loan book by a third in the next two years alone.

But tackling the bad loan problem at the rate the ECB and European officials would like will mean sacrificing capital, not least because the prices investors are willing to pay imply losses much deeper than the average 45% of NPEs provisioned by the banks.

“The pricing gap has definitely closed as demand picks up, but there is still a significant gap in many cases, particularly on secured loans,” said Justin Sulger, head of credit at Anacap Financial Partners, which has bought €9bn of bad Italian loans.

Italian banks have steadily been building up capital over the past few years – through various rights issues and through retained profit – to finance future writedowns. But the ECB has grown frustrated with the pace of progress and is concerned about its impact on new bank lending and the wider economy. It now wants to accelerate the process.

“Many banks are only now bringing assets to market that have been doubtful for some time – they simply couldn’t afford to sell previously or didn’t want to take losses,” said Sulger. ” But price targets are often still too high, and further capital losses are inevitable.”

Pincer movement

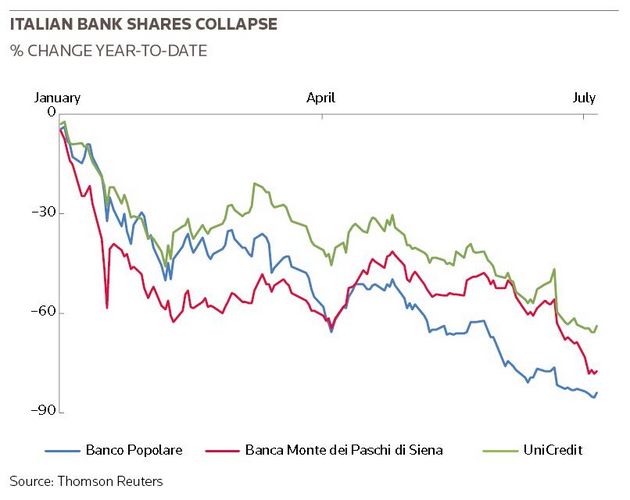

Markets haven’t reacted well to the EBA-ECB pincer movement. Some bank stocks are down by more than 50% this year, and some subordinated bonds are trading as low as 40 cents on the euro. The movements have severely constrained new issuance.

“This isn’t a good time to be doing this,” said another banker who works closely with Italian lenders, citing uncertainty around the UK’s referendum on EU membership already roiling markets. “But the ECB has been pushing for a clean-up for the last two years. Other solutions have reached the end of the road.”

While the timing is awful, current market turmoil might help the Italian government. Under EU rules designed to minimise the cost to taxpayers of bank rescues, government bailouts are only allowed after 8% of capital – equity and bonds – is bailed in.

But there are provisions to temporarily inject capital without bailing in other stakeholders during times of extreme system-wide financial stress. The Italian government could use the current market turmoil – and backdrop of Brexit – to do just that, and so avoid bailing in the retail bondholders it is so fearful of upsetting.

Goldman Sachs believes that would be sensible. “We view bail-ins as risky, with abundant scope for unintended consequences,” analysts from the bank wrote.

Whether the current market conditions are invoked or not, some believe this situation could have been avoided, and instead point to a European Commission obsession with shoehorning diverse banking business models into a single set of rules.

“Standardising the treatment of bad loans across Europe has disproportionately hit those countries where having NPEs and giving businesses some forbearance is part of normal business operations,” said Dan Davies, a senior research adviser at Frontline Analysts.

“However they resolve this, it was always optimistic to pretend that you were going to be able to sort out significant problems in any banking system and not have the state step in with some kind of bailout.”