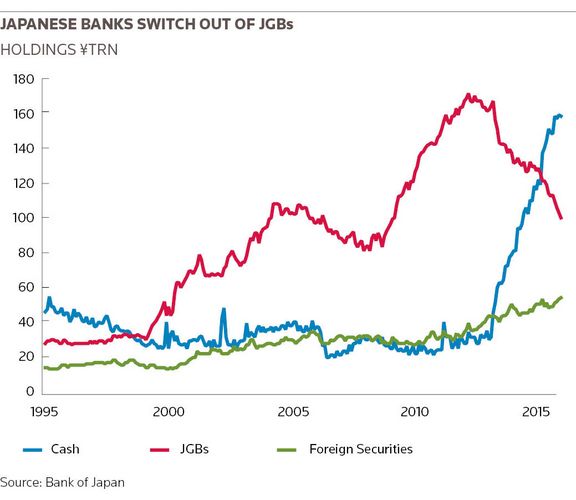

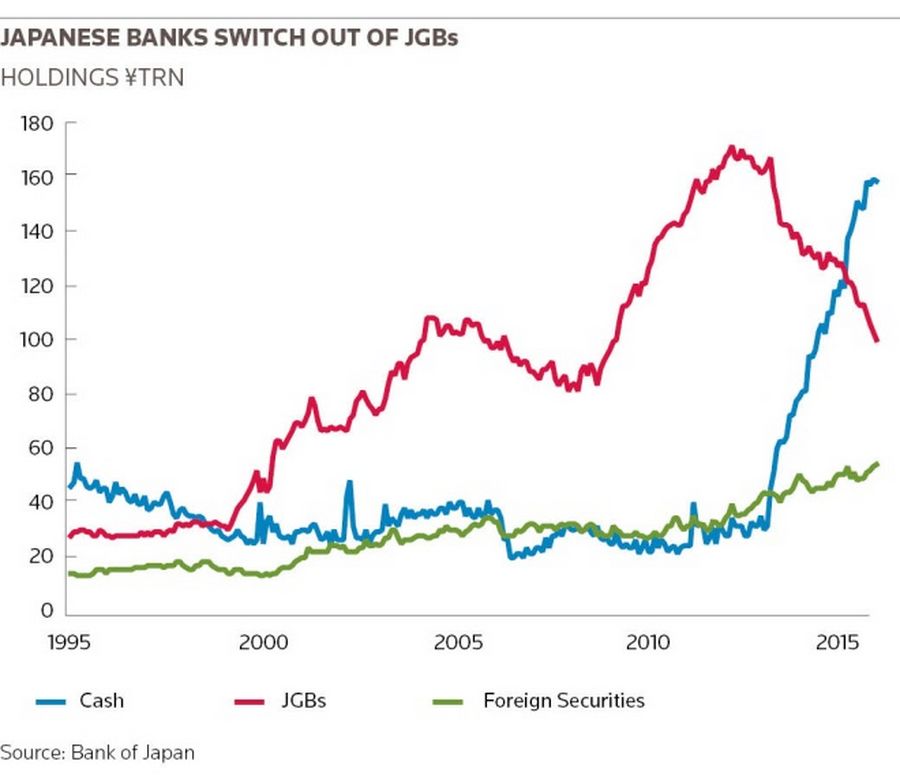

Japan’s banks are slowly shaking off the conservative habits that have defined the country’s financial system for three decades, and are rapidly selling down their giant holdings of Japanese government bonds as they seek to increase risk-taking at home and overseas.

JGB holdings have grown to epitomise the country’s financial paralysis since the bursting of the real estate bubble in the 1980s, as year after year banks bought more of the safe-haven securities while also reducing the proportion of assets allocated to lending.

But banks such as Mitsubishi UFJ, Sumitomo Mitsui and Mizuho have become heavy sellers of JGBs, unloading ¥70trn (US$625bn) over the past three years. The securities now make up less than 10% of banking assets in Japan, compared with almost double that in 2013.

Flush with cash from those sales, Japanese banks have begun to increase lending at home and abroad. Domestic bank lending is consistently growing at rates of more than 2% a year. Overseas, Japanese banks are now the biggest cross-border lenders of all, according to the Bank for International Settlements, after a doubling of the credit they extend over the past decade.

The financial sector is also powering an M&A boom, with deals involving Japanese companies at a 16-year high. Many expect such deals to increase as negative rates at the Bank of Japan force banks to lend or spend to avoid losses on their mammoth cash holdings.

“The role of megabanks will change substantially in the next four years or so,” said a board member at one of the country’s biggest banks. “Japan has to turn the corner and banks have to be at the centre of that change. We are at a turning point.”

Charge

Mizuho is leading that charge. Last year, it bought a US$36.5bn portfolio of US and Canadian corporate loans from RBS and hired 130 debt capital markets bankers. Meanwhile, in recent months Sumitomo Mitsui bought GE’s European sponsor finance business for US$2.2bn.

Koji Fujiwara, chief strategy officer at Mizuho, said the RBS purchase was just the start of a wider overseas expansion.

“The loan business is only the beginning of our overseas strategy – it is just an entrance,” he told IFR, adding that the bank would build on the new relationships that come from such deals to drive cross-selling in debt markets, trade finance, derivatives and foreign exchange. “It is the foundation for a complete horizontal expansion in overseas markets,” said Fujiwara.

Pushing banks and the wider corporate sector to take such risks again is a key tenet of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s three-pronged Abenomics programme, brought in to shake the world’s third-largest economy out of three decades of stagnation and deflation.

“The loan business is only the beginning of our overseas strategy – it is just an entrance”

Getting banks to lend more – to finance risk-taking – is seen as key. Policymakers feel banks have largely failed to fulfil that fundamental role in recent decades: in nominal terms, loans made by Japanese banks remain at 1990s levels despite a one-third increase in bank assets.

Akinari Horii, a former assistant governor at the BoJ who worked closely with banks in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, told IFR that banks just became too conservative – but added that Abenomics was starting to shake the sector out of its bad habits.

“Banking in Japan changed dramatically in the 1990s; the pendulum swung from one extreme to the other,” he said. “Banks became so conservative about lending, boards so careful – you could argue that the BoJ educated them too well. But now the megabanks believe in Abenomics. They see opportunities.”

QQE bid

An ¥80trn-a-year quantitative and qualitative easing programme from the BoJ is both encouraging and facilitating the unwinding of banks’ three-decade-long JGB trade, pushing up the price of JGBs to incentivise sales and providing a strong, reliable bid for the bonds.

But other parts of Abenomics are also pushing banks to change their ways. A new corporate governance regime brought in last year means banks now have to justify equity stakes they hold in key clients. The cross-holdings have been a cornerstone of bank-client relationships in Japan for more than 60 years.

Mitsubishi UFJ, Sumitomo Mitsui and Mizuho alone hold about ¥9trn of cross-holdings, and have separately committed to bringing those down. The sales will add to Japanese banks’ cash piles, which have quintupled over the past three years to a record ¥160trn. Japan’s megabanks are now the most cash-rich banks in the world.

“The megabanks have sold about ¥120bn of cross-holdings over the last year alone, and there is ¥2trn more to come over the next five years,” said Makoto Kuroda, a bank analyst at JP Morgan in Tokyo. “Coming on top of the JGB sales, this leaves banks with huge levels of cash – cash that urgently needs to be reinvested.”

“This leaves banks with huge levels of cash – cash that urgently needs to be reinvested”

That urgency has ticked up in recent weeks after the BoJ introduced negative deposit rates. Any further sales of JGBs or cross-holdings will create a headache for banks, which will need to find investment opportunities – or face having to pay up to park the cash at the central bank.

“Once, cash holdings provided Japanese banks and corporates with a valuable liquidity cushion and the deflationary environment meant there was no or very little cost of doing that,” said Yuichiro Wakatsuki, head of investment banking in Japan at Bank of America Merrill Lynch in Tokyo. “But there has been a paradigm shift as a result of Abenomics, and now by holding cash you risk destroying equity and corporate value.”

Certainly the advent of negative rates should push Japanese banks out of their lethargy. “For banks that are growing, the shift to negative rates is manageable, but for those that aren’t it is less so,” said Kuroda.

Shift in mentality

Bankers in Tokyo speak of a fundamental shift in the mentality of banks and corporates, with a new emphasis on profitability and return-on-equity.

“There is much more focus on ROE, on having the right capital structure, on putting money to work, and that is a direct result of the corporate governance changes,” said Wakatsuki. “Japan is becoming slowly more westernised. There is a change in thinking.”

But a wholesale shift towards more risk-taking doesn’t necessarily mean an easy ride for the country’s banks. Part of the reason bank lending remains at 1990s levels is because the demand from loans – especially from large corporates – remains subdued.

And that isn’t just because they too have been conservative. Corporate Japan sits on more cash than the banks themselves – around ¥220trn is deposited at domestic lenders, and more overseas. Such cash piles mean they have little need to borrow.

All this comes back to the perennial problem that has dogged the Japanese banking system for many years: too many deposits, and too few assets that yield a decent return.

“One of Abenomics’ biggest successes has been in pushing corporates to take more risks to guarantee their own future, pushing them to look abroad given the country’s limited growth,” said Tetsu Ozaki, wholesale chief executive at brokerage firm Nomura. “Many companies are now looking at acquisition opportunities outside Japan.”

Cash-rich

But he cautioned that a further M&A boom wouldn’t necessarily translate into a boon for the domestic banks. “Banks have huge levels of deposits, but there just aren’t sufficient investment opportunities here – Japanese corporates are cash-rich, and the country is over-banked. Banks know they have to do something.”

For that reason, banks are looking overseas. The Mizuho-RBS deal caught the headlines, but Japanese banks in general have been upping lending activity overseas over the past couple of years in a bid to generate higher returns. Outside the US, one in every six dollars lent globally now comes from a Japanese bank.

They have also been spending significant sums to buy loans made to non-Japanese borrowers on a piecemeal but regular basis from non-Japanese banks.

“Banks know they will have to go abroad for growth,” said a second board member at one of Japan’s largest banks.