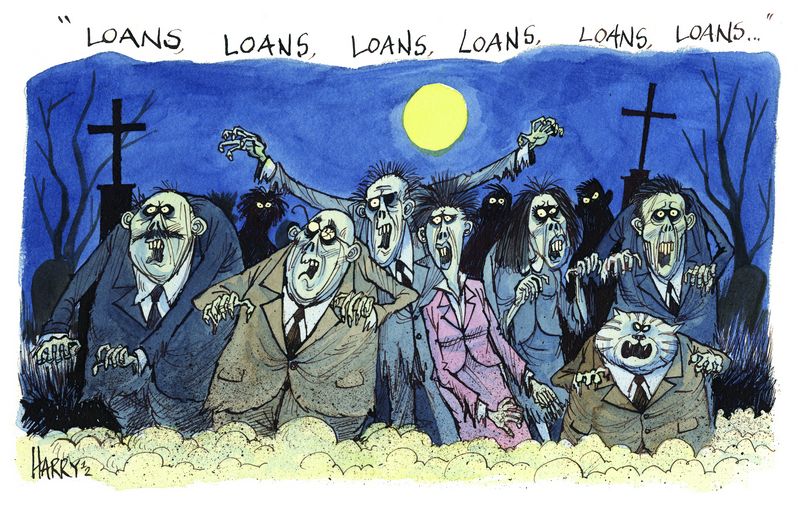

It is not easy to kill the loan markets. But with a sharp drop in volumes, the European syndications market certainly looked close to death in 2012. Nevertheless, bankers are confident that syndications will rebound strongly in the year ahead.

To see the full digital edition of the IFR Review of the Year, please <a href="http://edition.pagesuite-professional.co.uk//launch.aspx?eid=24f9e7f4-9d79-4e69-a475-1a3b43fb8580" onclick="window.open(this.href);return false;" onkeypress="window.open(this.href);return false;">click here</a>.

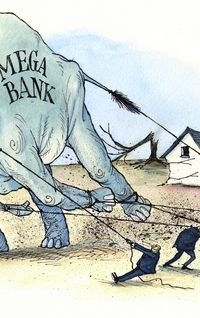

There is no escaping the fact that the loan market in Europe has had a really tough year if you look only at the volumes. Syndicated lending in Europe, the Middle East and Africa slipped 35% year on year to US$509bn in the first nine months of 2012, according to Thomson Reuters data. The gloom did not lift at all in the third quarter. At a fairly measly US$135bn, the third quarter was the lowest quarter by volume for the last three years and 37% down on the second quarter.

Yet loan bankers sound sanguine. “We came to the end of the cycle of refinancings at the end of last year,” said Jonathan Macdonald, head of global loan syndicate, EMEA and Asia-Pacific for Barclays. The bulk of the European loan market is in corporate refinancing, and most bankers agree that the majority of lines were refinanced between 2010 and the middle of last year. Given that the natural maturity of loans is around five years, there is pretty wide agreement that the cycle will start to pick up seriously again come 2014.

An understandable lowering of expectations from bankers aside, there are signs of a pick-up in activity – even in Southern Europe and despite the eurozone crisis. Italian gas distributor Snam pulled off a headline deal in August, allocating the reduced €9bn loan backing its split from Eni. Heart was taken not just from the fact that the deal got away, but from the fact that the margin the loan pays to cover Italian banks’ higher funding costs was only 300bp–350bp. At the start of the year, said bankers, the Italian premium could have been as much as 600bp.

Other Italian deals, including motorway financing, have bubbled away in the background as well. Motorway project company Tangenziale Esterna agreed a €120m term loan with Banca Popolare di Milano, Banca IMI and UBI-Centrobanca to help cover the construction costs of a ring road east of Milan. And Brebemi, another motorway financing company, has extended the maturity of its €546m bridge loan backing the Brescia-Bergamo-Milan Direct Motorway.

In Spain, the national lottery is in the process of raising €6bn in a syndicated loan. The loan for Sociedad Estatal Loterias y Apuestas del Estado will partially finance the government’s regional fund, along with an €8bn private placement provided by Spanish banks in mid-October and a €4bn payout from the Spanish Treasury. One banker close to the deal said it was “getting some traction”.

Some loan bankers are sceptical about how much can be read into these deals. Big national champions like Snam will always survive, and cynics suggest that enthusiasm for Loterias has as much to do with a desire to get on to the IPO as anything else.

“Last year we saw European banks go through a liquidity crisis. There was an increase in pricing, especially for lower rated companies,” said Damien Lamoril, head of loan syndicate for Societe Generale. Still, spreads have begun to stabilise, and the premium for non-core Europe has come in.

Room for hope

Similarly, at first glance the European leveraged loan market is in no better shape. European leveraged loan volumes in the first three quarters of the year reached only US$72.44bn, 42% down from the same period of last year. But here too there is room for hope.

Since the beginning of the year, the US has been a saviour of the European leveraged market, especially on larger transactions – with companies looking across the Atlantic simply to get deals away.

“While the US market has grown even stronger, European companies are now also going to the US because one of their operating currencies is US dollars, as the most recent cross-border deals have shown,” said Hoby Buvat, managing director of leveraged debt capital markets at Deutsche Bank.

She said that more nuanced pricing was developing, as investors differentiate deals according to leverage, sponsoring entity, use of proceeds, ratings and currency in a way that might not have happened in the past.

Buvat gave as one example German bandages maker BSN Medical, which repriced its €865m loans at the beginning of October. The company cut the margin on the dollar term loan B to 375bp over Libor and the euro term loan B to 425bp.

She compares that with the pricing on the £235m debt financing behind private equity firm Cinven’s £465m acquisition of British pharmaceutical company Mercury Pharma. The all-senior leveraged loans include a £60m six-year term loan A at 500bp over Libor; a £155m, seven-year term loan B at 600bp over; and a £20m six-year revolver at 500bp over.

“It was sterling, lower credit and a smaller institutional tranche,” Buvat said.

Not getting together

Nevertheless, there is no escaping the gloom that hung over 2012 when it came to M&A activity. M&A with EMEA involvement hit only US$723.7bn in the first nine months of year, a drop of 8.5% on the same period last year. The real shocker came in the third quarter, when volumes slumped 41.6% from the previous period. An indication of the depth of the problem can be seen in EMEA fees, which fell 35.4% to US$6.8bn in the first three quarters of the year, according to estimates from Thomson Reuters.

“This year we had expected more in terms of M&A volumes,” said Macdonald of Barclays. “At the time that was wishful thinking.”

There was of course some M&A activity – but it was thin on the ground. The largest deal of the third quarter was the US$14bn loan for Belgian brewing behemoth AB InBev’s takeover of Mexico’s Grupo Modelo, best known for Corona, and the US$8.5bn bridge loan for Nestle’s purchase of Pfizer Nutrition.

But if the year has been soft, there are signs that the market is starting to flicker back to life. “I am not sure that the statistics reflect what is really starting to happen,” said Robert Boehm, head of DCM loans for Commerzbank, and chairman of the loan market association. “There is a noticeable increase in M&A discussions going on, and it is worth remembering that loan activity is the result of these discussions.”

Boehm pointed to the aborted US$45bn deal between BAE and EADS in mid-October as a positive sign. “Even if this was not intended as a loan market solution, it is a sign that corporations are starting to think big again,” he said.

“Loan volumes in Europe will be up around 10%–20%. We are going to start to see companies manage their maturities and take advantage of lower pricing”

The US$32.5bn loan that will allow Rosneft to buy TNK-BP is another case in point. Though the deal is to be self-arranged and tightly priced, banks were queueing up to be involved. While the main draw was potential ancillary business, it still shows that the loan market is the venue of choice for M&A financings – especially the larger ones.

In the aftermath of the long-expected bloodletting at UBS at the end of October, some nervousness as to future headcounts in loan teams might be expected. Yet while there may still be some excess capacity in the industry that has not been addressed since 2007, many in the market are upbeat. “I don’t expect massive headcount reductions unless volumes are very low next year,” said one banker.

And most don’t expect that to happen. “I expect markets to improve next year, but I do not expect a massive rally,” said SG’s Lamoril. “Loan volumes in Europe will be up around 10%–20%. We are going to start to see companies manage their maturities and take advantage of lower pricing.”