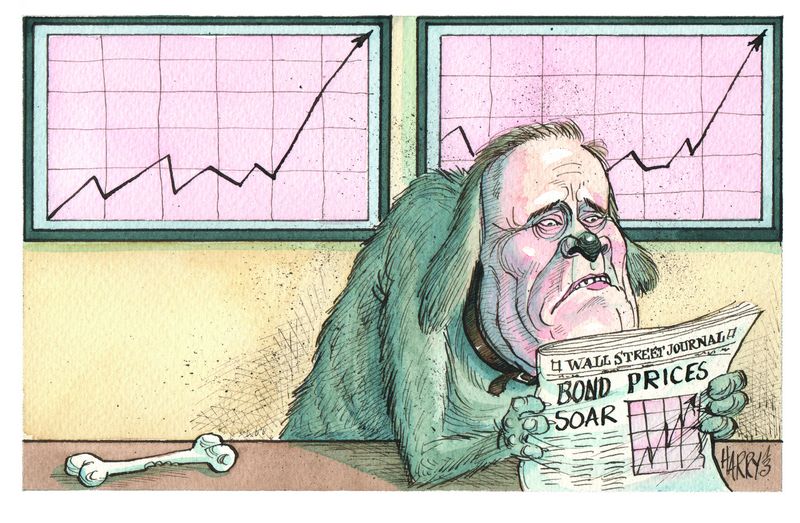

An old bond market dog, as Anthony Peters describes himself, takes a look at the state of the secondary markets – and despairs. 2013 could have been the year when a new world in the markets began to emerge. If so, it won’t be one to his liking.

Markets have done rather well in 2013. Equities have returned handsomely, quite in line with predictions, and bonds will come out of the year significantly better than had been forecast. Issuance is booming across the world, so equity and debt capital market folks have good reason to pour themselves a stiff one and look back on a year with some satisfaction.

Down on the coalface of sales and trading, however, things look less cheerful. I recently had dinner with a friend who is a country head for debt and rates at one of the main US firms. In a truly miserable mood, he said he felt like a hamster in a wheel, having to run just to stand still.

I have known him for many years and hold him in the highest regard, both in terms of professional ability and personal integrity. The latter probably damaged him in the easy times and now, in his mid-40s, he has a big mortgage which didn’t look that big when he took it out, children at school and management breathing down his neck.

“Oh, X has just done this deal and Y has just done that one. Why aren’t you doing that too?”

“Because, sir, we don’t have the risk limits, we don’t have the technology and we can’t deliver the product. Apart from that, I could do it tomorrow.”

My friend was thoroughly depressed. Most of his bonuses of the past few years are locked up in deferred stock. No other employer is going to buy him out of them and if he resigns, he forfeits the lot. The only viable option for him is to wait to get fired, at which point all deferred compensation vests instantly. This is not a good place to be and certainly not an environment that motivates. And all the while his income is dropping.

On the other side of the coin, I spoke to another salesman, in his early 30s who bats for one of the other US institutions. He admits he is very lucky not to be five or 10 years older. He never experienced the fat years with the big compensation packages, hence hasn’t found himself lumbered with a cost base which he would now be struggling to fund. He doesn’t live in Chelsea, doesn’t collect fancy cars and has no illusions of ever being able to.

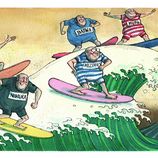

Struggling to stay afloat

The sharply diminished liquidity of credit and government bond markets – even some of the latter are beginning to trade “by appointment only” – has supposedly turned old market-makers into agency brokers. But, trust me, even those brokers who can, by the nature of their set-up, produce at a significantly more efficient cost than the big banks, are struggling to keep afloat.

Unless regulators take a more sensible approach to trading and inventory, another major wave of cost-cutting will be upon us. Bond markets tend to be all bid or all offer and they need the buffering ability of the banks’ balance sheets to keep them working.

Former Fed chairman and fully paid-up guru Paul Volcker might have meant well when he railed against proprietary trading, but sadly he forgot to tell anyone where market-making ends and speculative proprietary trading begins.

As the last ripples of 2007–08 fade away, this has become the big unanswered question and one which is best measured with that famous piece of string. Without the revenues from secondary trading and the carry from inventory, it is hard to finance not just DCM operations, but other areas such as European ECM and M&A which always seem just about to pay off. As a result, many banks will soon give up on their efforts to be omnipresent one-stop shops – and that means a large-scale resizing of the industry.

My chum has grasped that once you’ve passed 45 and you’re not on a trajectory towards top management, bonuses begin to become a luxury – so do, truth be told, paycheques once you’re over 50. However, chances of “making your pile”, “being done”, at that age is a diminishing prospect and as such, working in an industry which is prone to spit you out just when you you’re beginning to understand what you’re doing, is mightily depressing.

Withering on the vine

Persistently low yields and the massive need for income have created a sellers’ market, especially for higher-risk vanilla products. Investors have broadly become wary of structures which try to make the whole of the credit risk look to be lower than the sum of its parts.

Idiosyncratic risk is so much more transparent than systemic risk, or so investors believe. And thus, debut single borrower credits come to the public markets on a more or less daily basis without much in the way of a discount for illiquidity and are instantly snapped up. If investors need the yield, they will buy the story. Meanwhile, traditional sales and trading skills are withering on the vine.

It may of course be that these are no longer needed because bonds are going back to being simple buy-and-hold generators of a predictable stream of coupon income. Bit by bit regulation has squeezed the living daylights out of banks’ ability to make liquid markets and what was once a high-octane can-do culture is deteriorating into a no-can-do, no-care-to-do world.

Opinions are divided as to whether the sharp decline in earnings in the fixed-income, currencies and commodities space which we have experienced in the second half of 2013 is just a temporary blip or the beginning of a “new normal”.

The answer lies not with issuers, banks or investors, but with the authorities who applied the brakes but who might now need to ease off again.

The capital required to trade has become more expensive and if transparency is aimed at reducing the cost of doing business for the buyside, then banks will continue to vote with their feet. By the end of 2014, FICC global headcount will most likely be 10% lower, maybe more.

Rather than further globalisation, we will quite possibly see a shift towards greater regional fragmentation. It is just possible that, quite simply, the mother lode is exhausted and the mines are shutting down.

The world of debt, be it at government or at corporate level, is in a state of transition. 2013 might prove to have been the year when the struggle to maintain what was came to an end, and when the urge to move towards what is going to be began in earnest. Along the way, the dinosaurs of the credit boom will be sacrificed and the small, unprepossessing mammals of the new order will begin to take over.

One result of all this is that the latest generation of those joining the industry will be decently compensated, but will no longer comprise the cream of the age group.

For a brief period during the dotcom boom of the late 1990s, the brightest and the best were streaming out of the investment banks in order to make their fortunes as tech entrepreneurs. By the spring of 2001 they were all barrelling back again. This time, I suspect, the bright young things will leave for good.

To see the full digital edition of the IFR Review of the Year, please click here.

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email gloria.balbastro@thomsonreuters.com