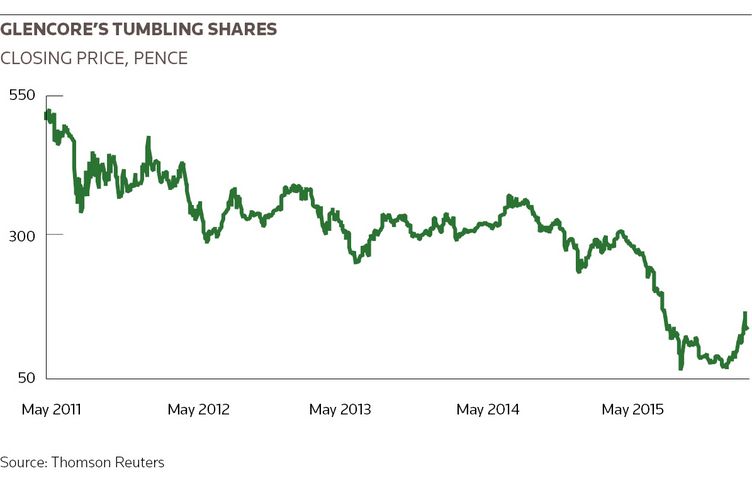

Markets were panicking about Glencore on the morning of January 14. A rout in metals, agricultural and energy prices had hit the commodity trading company hard, making it a target for short-sellers who were betting on its collapse. Glencore shares started trading that morning at 70.83p, their lowest open ever and down almost 90% from its IPO less than five years earlier. Its bonds with just a year to maturity were yielding over 10%, an unmistakeable sign of stress, while the cost of five-year default protection was quoted above 1,000bp for the first time since October 2008.

“People were starting to see ghosts,” said one banker who has closely worked with the company for a decade. “They thought Glencore was going bankrupt.”

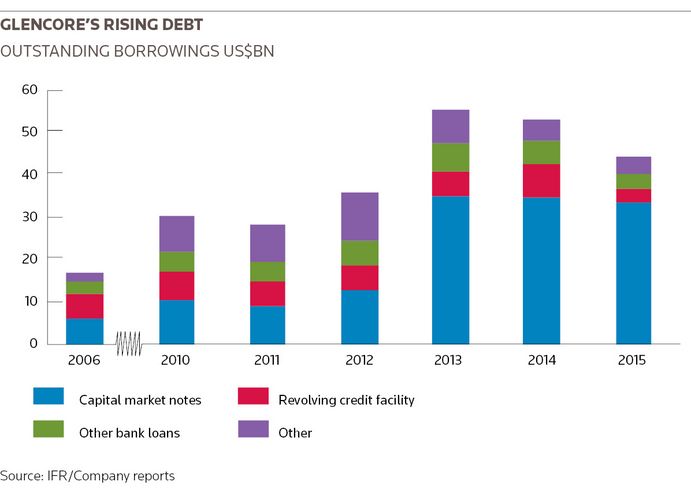

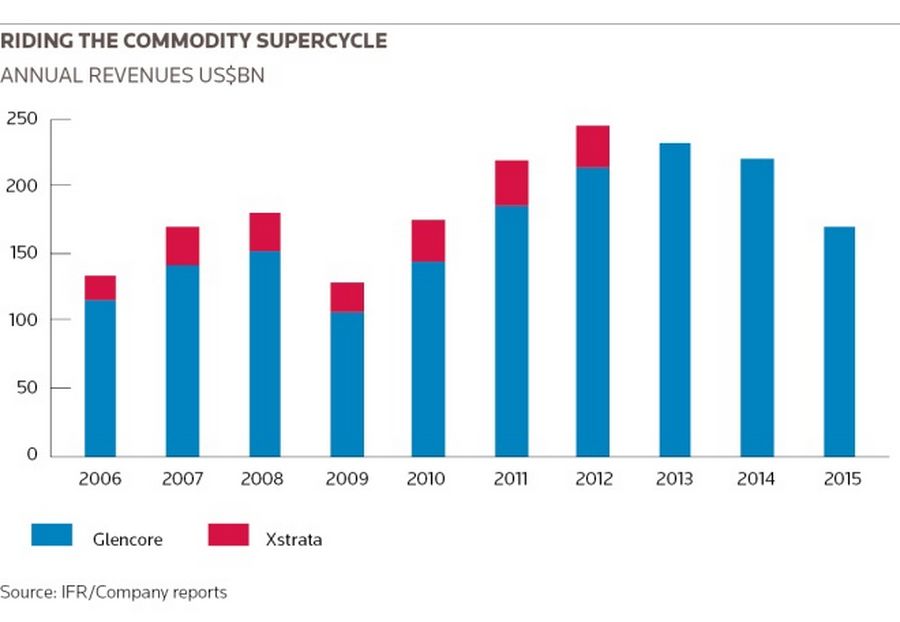

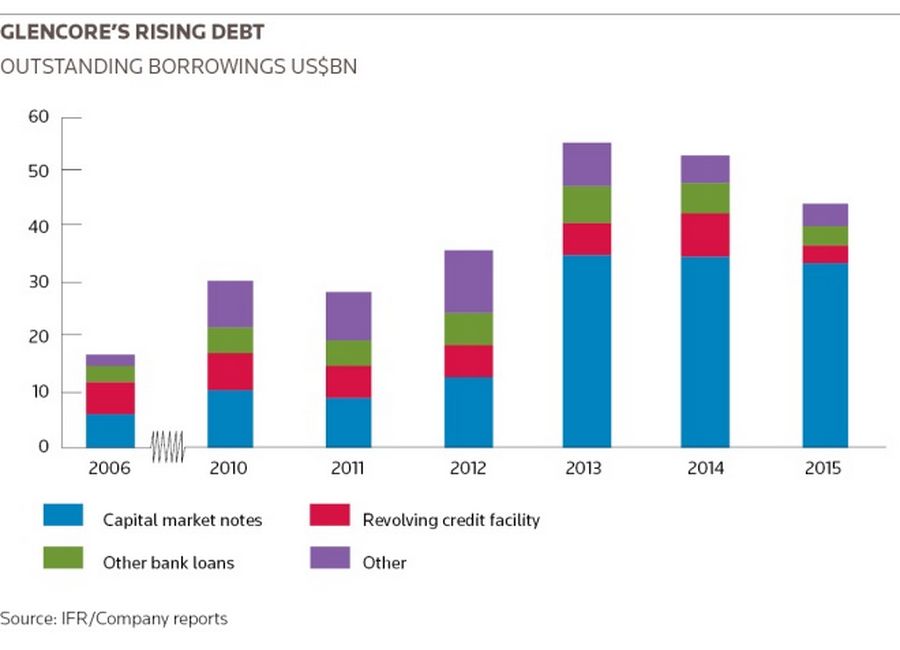

From the outside, there looked to be plenty of reason to worry. Lured by surging commodity prices and growing demand from China, the company had gorged on cheap debt in the late 2000s, doubling its borrowings at a time when much of the corporate world was cutting back. A merger with miner Xstrata in 2013, just as commodity prices were peaking, left the company highly leveraged and owing more than US$55bn to its creditors. As commodity prices took another leg down last summer, the storm clouds growing over the company became too large to ignore. Glencore hastily put together a US$10.2bn debt reduction plan, but that did little to settle investor nerves. Short-sellers were circling, investors were fleeing. Many thought Glencore’s days were numbered.

But Ivan Glasenberg was not overly concerned. Glencore’s chief executive had first made a name for himself as a champion speed-walker, a sport whose main rule is to always keep one foot on the ground. While Glencore’s debt looked worrying from the outside, Glasenberg remained rooted, confident the company had the full backing of its banks. Glencore was, to put it mildly, one of their most important clients. In a good year it generated hundreds of millions in revenue for the banks through interest on its loans, bond underwriting fees, advisory work, trading and letters of credit. Glasenberg knew they would stand behind the company during its time of need: he had an ace up his sleeve, and he was ready to use it.

A consortium of banks had extended an US$8.45bn one-year loan to Glencore the previous May, and, although it still had months until maturity, uncertainty around whether or not the company might be able to refinance that debt was helping feed the fear that the short-sellers were preying on. After some internal debate, and having spoken to some of its most senior lenders, Glencore decided it needed to take that uncertainty off the table. So on the morning of January 14, just as market confidence in the company was reaching its lowest ebb, Glasenberg made his move. Glencore’s finance department contacted the banks and asked them to increase their lending commitments to the company at its time of need.

Many bankers were caught off guard. Not only was the market climate extremely volatile at that moment, Glencore had not been expected to refinance the one-year loan for a couple more months. And the company did not hesitate to tighten the screws: it essentially gave the banks an ultimatum, telling those that had lent it US$150m each the previous year that they now had to commit US$250m to get in on the deal.

“It’s a testament to the strength of our banking relationships that we had the confidence to launch the refinancing early”

It was the kind of master stroke – brash, confident, outrageous to some and ultimately successful – that had long defined the company. Glasenberg and his finance team knew the banks would have little choice but to say yes – and say yes they did. Glencore shares rallied more than 9% on the day that the refinancing was announced. Within four weeks, the commodity trader had 37 banks on board – more than on the previous loan, which had come during the relative calm of the previous May – and more money committed than it was looking to borrow. With the overhang of the loan out the way, Glencore’s share price doubled over the following few weeks. The company had the full and unquestioned backing of its banks, and now everyone in the market could see so.

“It’s a testament to the strength of our banking relationships that we had the confidence to launch the refinancing early,” Glencore’s chief financial officer, Steve Kalmin, told IFR in a rare press interview. “The vast majority of banks have known our business for decades, with some relationships going back 40 years. They’re not only your capital providers – they’re your cash managers, LC providers, foreign exchange counterparts, risk management enablers, et cetera. They have day-to-day visibility into your business and access to management, which provides very high levels of comfort.”

Brash confidence

Brashness and confidence may have eventually won the day, but many people close to the company believe it was precisely those traits that had got Glencore into trouble in the first place. Run out of a squat five-story campus on the outskirts of the Swiss town of Baar, the company had spent the first 37 years of its existence as a private entity. Founded by American billionaire Marc Rich in 1974, Glencore seemed to revel in its ability to operate out of the public eye. Rich spent years on the FBI’s most-wanted list for illegally making oil deals with Iran, which was then under US sanctions. President Bill Clinton pardoned Rich, whose wife was a generous Clinton donor, on his last day in office.

Glencore’s IPO in May 2011 changed all that. Before going public, the company’s decisions really only had to be justified to a small clique of managers at the firm. Those insiders were about to become tremendously wealthy: the IPO would turn a handful of them into billionaires overnight. The US$10bn listing, which valued the company at US$60bn, is the largest ever executed on the London Stock Exchange. CEO Glasenberg’s 15.8% stake, based on the 530p listing price, was worth just shy of US$9.5bn.

But with the IPO came a new responsibility, and a legal requirement, to regularly update outside investors and become more accountable. “Most companies are quite attuned to the regular investor,” said a second banker who also worked with the company for many years. “But Glencore had to bring in a lot of new talent: IR, PR and finance.”

Those new responsibilities came into sharp focus last summer as commodity prices plummeted. When Glencore released first-half earnings in August 2015, the market mood was bearish on commodities. Yet Glasenberg remained irrepressibly upbeat, comparing the situation to just before the last bull market had started. “The world was bearish in 2003,” he told analysts. “And then suddenly the big kicker came. We had weak commodity prices and within two, three months, suddenly the market turned.”

Although both Glasenberg and Kalmin remained relatively bullish on the way that Glencore was positioned as a business medium-term, they could not completely ignore market concerns over the company’s debt. In a nod to that anxiety, Kalmin told analysts that Glencore would bring down its net debt – a lower measurement of borrowings, preferred by the company, that subtracts commodities on its books available for sale – by about US$2.7bn over the next 18 months.

“They realised they had made a mistake with running the balance sheet”

But meeting investors on the road just days later, it became clear that Glencore management had badly misjudged sentiment. Investors demanded that the company do more to get its debt load under control. Over the next fortnight, the finance team back in Baar burned the midnight oil to cobble together a new US$10.2bn debt reduction plan that would include halting the dividend, selling new shares, disposing of assets and cutting costs. The plan targeted a reduction in the commodity traders’ borrowing base almost four times larger than that promised by Kalmin only a couple of weeks earlier.

“When they went on the roadshow, they heard from investors the balance sheet was not right,” said the first banker. “They realised they had made a mistake with running the balance sheet. Then they reacted extremely quickly.”

Fateful

Glencore might never have had to worry about outside investors if it had not been for Glasenberg’s fateful decision to merge with Xstrata. Glencore first acquired a large stake in the company, at the time just a small Swiss infrastructure entity known as Sudelektra, in 1990. By 2001, Glencore had a vision for the entity: Xstrata would become a miner in its own right through asset purchases, and would sell its commodities to buyers through Glencore, in a close and mutually beneficial partnership. Glasenberg lured Mick Davis, an old school-friend from South Africa, to run Xstrata.

The first deal between the two men was auspicious. Glencore had tried but failed to list Enex Resources, a subsidiary housing its coal mining operations in Australia and South Africa. Bankers were en route to meet potential investors at the World Trade Center in New York when the twin towers were brought down on September 11 2001. The bankers survived but the listing was finished. As markets panicked in the wake of the attack, coal prices collapsed, leaving investors with little appetite for the stock.

Glasenberg pulled the listing. But within weeks, Davis approached him with an idea: Xstrata would buy Enex for US$2.5bn. It was the start of a whirlwind expansion for both companies. Over the next decade, Davis grew Xstrata from a US$600m-a-year upstart into a US$34bn-a-year giant through a series of bolt-on acquisitions. The purchase of MIM Holdings, Australia’s largest independent miner, doubled the size of Xstrata overnight. Meanwhile Glencore used its Xstrata shares, which had risen in price exponentially, as collateral to borrow US$2.7bn to help fuel its own expansion.

But Davis, who had extensive experience in utilities and commodities, and had been the CFO of Billiton, another mining giant, was keenly aware that he could not simply run everything to please Glasenberg. Xstrata was a public company as well, and now a very large one, with its own investors and their own concerns. The two former school chums soon found themselves at odds.

“Glencore wasn’t happy about the way [Xstrata] was being managed,” said the first banker. “They were angry at the time. Not publicly, but they were definitely angry.”

The rift deepened over time. Glasenberg was frustrated that Glencore was not getting more business from its little brother to market the commodities Xstrata dug from the ground. When Xstrata was approached with a takeover offer from Vale, he vetoed it because he could not get a similar commitment from the Brazilian miner to sell its wares through Glencore.

Davis irked Glasenberg further in 2009 with an Xstrata rights issue to tackle the company’s finances. Glencore, which was coming under strains of its own, did not have enough cash available to take up its entitlement. Wary of becoming diluted — and thus having even less sway in Xstrata’s decision-making — Glasenberg was forced to transfer coal assets to Xstrata in order to pay Glencore’s share.

“Ivan didn’t understand that, as a publicly listed company, you can’t just have a cosy little deal with your biggest shareholder”

“Ivan didn’t want Mick to do the deal, because Glencore didn’t have the cash to participate,” said one Xstrata insider.

“The relationship with Glencore started very well in the beginning. It was key to Xstrata’s initial success, supporting early rights issues, marketing its produce and providing advice. But as Mick developed and built his own team, they did just drift apart,” the insider told IFR.

“Ivan didn’t understand that, as a publicly listed company, you can’t just have a cosy little deal with your biggest shareholder. You have to do what’s in the interest of all of them.”

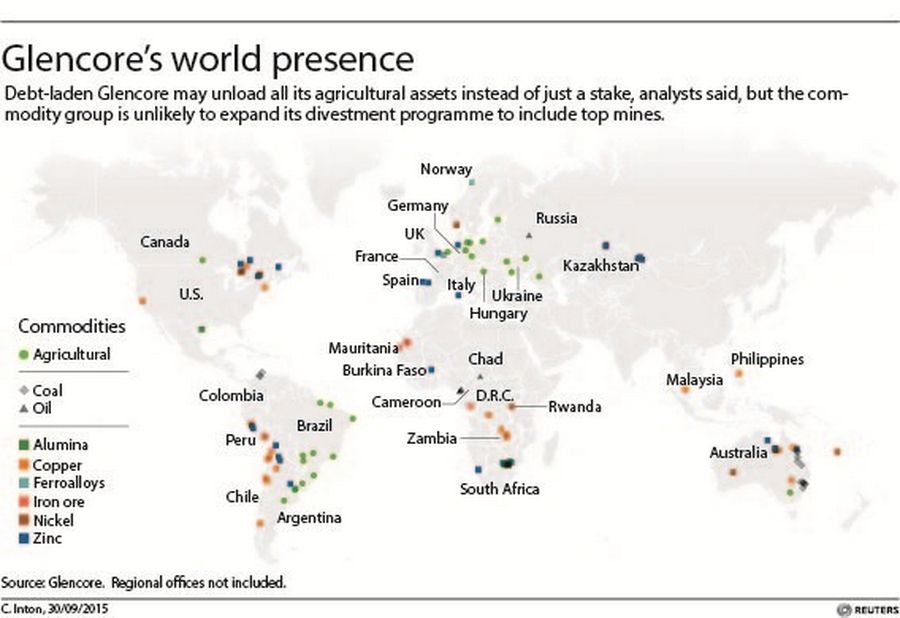

As Xstrata increasingly went its own way, Glasenberg and Glencore found themselves at a crossroads. One option was simply to up stumps: sell the one-third stake in Xstrata and focus on its own commodities-trading company. But Glasenberg saw an awful lot of value in taking full control of Xstrata. Reining in some excesses and fully integrating the miner with Glencore’s trading operations would guarantee the physical commodity volumes to put through its trading business, creating a vertical with staggering possibilities; indeed the merged entity would be one of the largest commodity players in the world.

“The two companies found themselves continually bumping up against each other,” said another banker who has worked closely with both for many years. “It became clear Glasenberg had two choices: divorce or merge.”

But in order to merge, Glencore would have to transform itself into a public company and expose itself to the intense scrutiny of the public markets. Only by going public and creating a liquid equity base would Glencore have the currency to merge with Xstrata. For a company that had long operated in the shadows, that would be a change unlike any other.

Leveraging up

Debt had been Glencore’s friend in the years running up to the Xstrata merger, allowing the company to leverage up its balance sheet and take full advantage of the commodities boom. From 2006 to 2012, on the eve of the merger, the company’s borrowings had doubled from US$16.8bn to US$35.5bn.

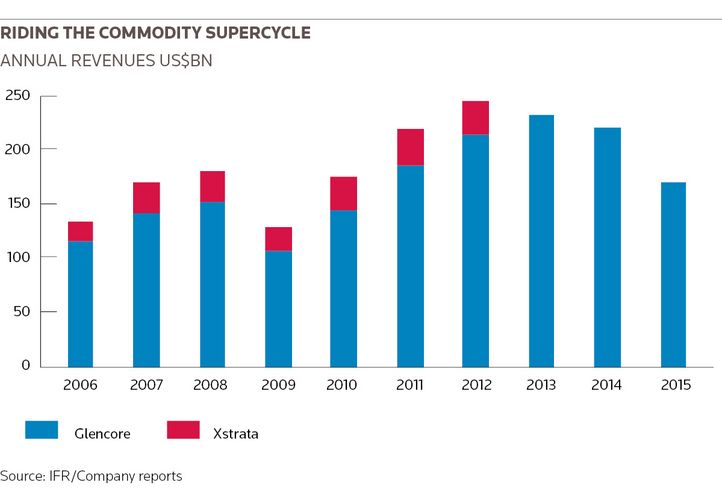

The bigger balance sheet gave Glencore the ability to trade bigger volumes, hold inventory for longer and expand its shipping operations. By 2012, its annual revenue was an eye-watering US$214bn – almost double what it brought in six years earlier – and it was said to have more vessels at sea than the Royal Navy. Relatively unknown outside the commodity markets, Glencore was bringing in more revenues than General Electric, AT&T or JP Morgan — indeed more than any bank on the planet.

Once the merger went through, the combined company was sitting on US$55.5bn of debt – a significant burden once commodity prices began to tumble. And the company was no longer focused on trading, the thing it knew how to do best. Glencore’s primary business had always been marketing or, more accurately, arbitrage. It bought a commodity in one place and then shipped it to another part of the world where that commodity was selling for a higher price. The new combined entity, very briefly known as Glencore Xstrata, was much more exposed to the capital-intensive business of extracting those commodities out of the ground. As a pure commodity trader, Glencore had always been nimble enough to quickly cut balance sheet when the need arose. But mining meant committing capital for years, if not decades. It had become less agile at precisely the moment it needed agility the most.

“They bought Xstrata precisely at the top of the market,” said Jim Chanos, founder of Kynikos Associates, a New York-based hedge fund that has been a short-seller of Glencore stock ever since the company went public in 2011.

“That is easy evidence that they got the big-picture thing wrong,” he told IFR. “It transformed the company and saddled them with a lot of debt. It made no sense.”

The negatives associated with the merger became clear almost immediately. On the first joint reporting date in August 2013, the company booked a statutory day-one goodwill impairment of US$7.6bn in relation to the deal, due to what it called the “broader negative mining industry environment”. Total writedowns for the first half of the year alone were more than US$10bn — much of it due to the rapid expansion of Xstrata in the previous years.

“The capital invested by commodity producers over the past decade has dwarfed returns to shareholders,” Glasenberg said in a statement at the time. “Many commodities now face near-term oversupply and unsustainable returns, despite robust demand.”

“They bought Xstrata precisely at the top of the market….It transformed the company and saddled them with a lot of debt. It made no sense”

As commodities softened in the ensuing years, the pain deepened. Last year, Glencore’s revenue was down to US$170bn – 30% below the combined revenues of the two independent companies in the year before the deal, and well below Glencore’s pre-merger earnings alone. In the last three years, the company has booked losses of nearly US$11bn, or roughly what Glencore booked in profits in the five years before the merger.

With those kinds of woeful results, the market started betting heavily against the company. With an ocean of debt, declining revenues, repeated writedowns and a balance sheet that seemed to be out of control, Glencore looked vulnerable – and the short-sellers began to smell blood. At one point short positions were equivalent to around 12% of the company’s stock.

Debt reduction

Last August, as Glencore was putting together its hasty debt reduction plan, Silver Wheaton got a call. The Canadian precious metals streaming company had spent years courting first Xstrata and then Glencore, hoping to get its hands on the silver that was being generated as a by-product at one of the Swiss commodity giant’s copper and zinc mines in Peru. Silver Wheaton made its money through long-term deals on silver streams, and the Peruvian operation looked ideal. Chief executive Randy Smallwood, who was one of the company’s founders, had approached Glencore repeatedly about a streaming deal. Each time the answer was no.

So no one was more surprised than he when the phone rang one day and it was Glencore on the line, looking to make a deal.

“Antomina has always been right at the top of our list, it is one of the best mines in the world,” Smallwood told IFR. “We had talked to Glencore in the past – about four or five times – just bringing it up as a possible opportunity. But at the time they just didn’t have a need for capital… Then they did have a need for capital, in terms of trying to pay down their debt. All of a sudden there was interest in doing a stream on Antomina.”

“We had talked to Glencore in the past – about four or five times – just bringing it up as a possible opportunity. But at the time they just didn’t have a need for capital”

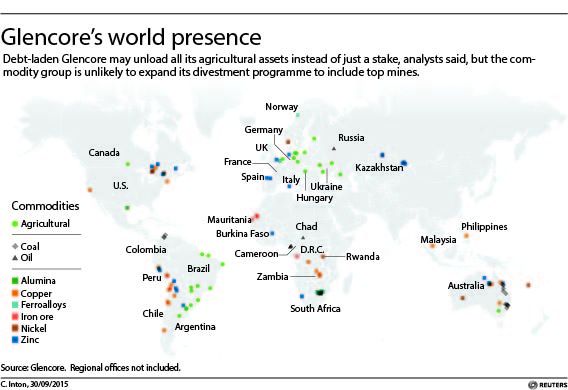

It was another sign of how much Glencore’s star had fallen. In the past it had been the one that made the large advances and the unexpected acquisitions, often raising eyebrows with its swashbuckling forays into parts of the world no one else seemed to want to touch: US$300m for the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s state electricity company; US$500m for Chad’s national oil concern. Now it was knocking on the door of Silver Wheaton, a fraction of its size, for money.

Kalmin, Glencore’s CFO, downplayed the decision, saying the company had already been “in the process of planning for the streaming transactions”. Apart from a streaming deal with Silver Wheaton in the mid-2000s, Glencore’s investor relations website makes no mention of any other similar agreements.

“Precious metals are non-core, as we do not trade them,” Kalmin said.

He added that more non-core disposals would follow, including the sale of Glencore’s agricultural business. “The strategic and financial sense of these transactions was only reinforced as the industrial commodity environment weakened,” he said.

Meanwhile, Glencore was also sounding out its biggest shareholders about another potentially more contentious part of the debt plan. Executives flew to Chicago and the home of Harris Associates – Glencore’s third-biggest shareholder, after Glasenberg and the sovereign wealth fund of Qatar.

Harris had spent the summer buying large chunks of Glencore stock, a bet that had soured and heavily weighed on the fund. Now the Glencore execs had arrived with an additional dose of bad news: they wanted more money.

“They came in person,” said David Herro, Harris’s chief investment officer of international equity.

“They went around saying: ‘This is what we are thinking of doing, are you aboard?’ My view was that this is the worst thing. It is like going to the doctor: you don’t want to hear you want to raise equity. But as much as the medicine tasted bitter, I really think it was the right thing to do. They hadn’t expected the price of these commodities to fall as aggressively as they had, and they would rather be safe than sorry. I couldn’t argue with that.”

The plan was to sell US$2.5bn of new stock, which together with a halt in the dividend would account for around half of the US$10.2bn debt reduction plan.

It was a controversial option, and one that sparked a fierce debate within the company. Many senior managers – as shareholders – would have to commit more of their own money in order to avoid having their stakes diluted by the equity raise.

Those commitments were costly for everyone concerned. Glasenberg subscribed for shares valued at £137.64m to maintain a stake of 8.42%, while Daniel Mate, the head of zinc and copper, spent £52.71m to neutralise the dilution of his 3.22% holding. Director Telis Mistakidis spent £51.8m to stand still at 3.17%. Kalmin meanwhile spent £9m of his own money to back the deal.

“What we certainly got wrong here is that, when we first started buying, we should probably have stress-tested the balance sheet to price movements a little better, because they were carrying too much debt given the volatility,” said Herro, whose firm also went along with it and bought into the deal.

“But they have gone through the right steps to basically de-risk that, and if you look at what they have done since the summer – the equity sale, the asset sales and the asset sales to come – and given that they are taking costs out the business, this company isn’t going under. It isn’t a black hole, which is what the shorts’ story was.”

Confident

After all of this, by mid-September Glencore management felt confident they had finally drawn a line under the problems. By committing their own money, they had shown personal confidence in the strategy in the most telling way possible – and they expected the rest of the market to agree.

It did not. On September 28, precisely three weeks after the newly formulated debt reduction plan had been unveiled, Glencore shares lost nearly 30% in one day, its worst trading session since going public. Glencore had misread the mood again.

The company’s press department scrambled to change the narrative, saying “speculation” about Glencore’s future was unfounded and insisting that it had taken the proper steps to survive the storm.

“Our business remains operationally and financially robust – we have positive cashflow, good liquidity and absolutely no solvency issues,” it said.

“We are getting on and delivering a suite of measures to reduce our debt levels by up to US$10.2bn. Glencore has no debt covenants and continues to retain strong lines of credit and secure access to funding, thanks to long-term relationships we have with the banks.”

While that may have been true, the short-sellers were nevertheless dictating how Glencore was being perceived in the market.

“Ivan Glasenberg had this amazing reputation, but if you think about it, it was really based on the basis of a once-in-a-lifetime global commodities bull market”

“Ivan Glasenberg had this amazing reputation, but if you think about it, it was really based on the basis of a once-in-a-lifetime global commodities bull market,” said one short-seller. “He really earned his chops post-Marc Rich in a commodity market that did nothing but go up. The minute the markets went down – and they’d been boasting for years how their traders could always make money and sense which way prices were going – perception changed.”

And that was a source of tremendous frustration within the company about what it saw as a campaign by short-sellers to drive the stock down. “There is a huge disruptive element to the financial communities,” one insider told IFR. “They hunt in packs and they use organisations such as the media as their mouthpiece.”

Whatever the truth or otherwise of that contention, it was still essential for Glencore to turn sentiment back in its favour.

Trying to regain the upper hand, Glasenberg and Kalmin announced in December that the debt reduction target would be raised to US$13bn – and that the target for asset sales would be double what had been announced in September. Capital expenditure would be cut further. Board members said the plan was to under-promise and over-deliver, hence the revised debt reduction targets.

But bankers close to the company say the management had still failed to get to grips with just how worried the market was about Glencore’s debt. Despite the latest round of promises, Glencore stock just kept falling. With the stock trading at about 15% of the IPO price, it was the worst Christmas – at least financially – anyone on the board had experienced in a very long time.

Stepping up

The decision to give the banks the loans ultimatum was made just after the Christmas and New Year break. Glencore was of course in regular contact with the banks, and it believed that the private loan market that had bolstered it when it was still a private concern would step up to the plate once more.

This time the company calculated correctly: bankers who committed to the refinancing told IFR they had never had any significant concerns about Glencore’s viability.

“People didn’t understand the relationship they had with their banks,” said one of the lenders who committed new cash.

By the time Glencore released its earnings at the beginning of March, progress had already been achieved: as well as doing the equity placement and cutting the dividend, the company had also cut capital expenditure and made US$1.6bn of asset sales – including US$900m from the Silver Wharton deal. In a bid to stay ahead of the curve, the company committed to further asset sales, targeting up to US$5bn this year alone, up from US$2bn when the debt reduction plan was first announced.

There is no question that much remains to be done. Glencore’s own targets call for net debt to be slashed to US$15bn by the end of 2017 from US$25.9bn at the end of last year. And while Glencore seems to have won back some equity investor confidence for now – the share price is currently around 150p, more than double where it was during the depths of January – it has yet to prove itself in the other big public market: the bond market.

Indeed, 2017 and 2018 are years with large bond maturities for Glencore: about US$4.7bn and US$4.2bn of bonds need to be repaid in those years respectively. Despite everything it has done, including more than US$500m of bond buybacks to reduce its debt load, bondholders remain wary: yields on its outstanding issues are still high, and the company, once a regular issuer, has not done a sizeable bond deal in a year. Glencore’s 2020 US dollar bonds that printed last April with a coupon of just 2.875% are currently yielding around 6%. At those levels, bankers say, it would be too expensive for Glencore to try to print new bonds.

Not surprisingly, Glencore is still confident.

“At some stage, the fundamentals, supported by the quality and strength of your business and asset base will reassert themselves,” Kalmin told IFR. “However, at this stage we need to plan for an environment in which commodity prices could remain flat or even go materially lower for a sustained period of time.”

Equally unsurprisingly, not everyone in the market is convinced. Revenues were already the lowest in years when the company released earnings in March, and writedowns on legacy Xstrata assets continue to hurt – the company made a US$5bn loss last year. What is more, as it disposes of more assets, the short-sellers are betting that its earnings capacity will be further dented, making it more difficult for the company to service debt.

“What has surprised us is just how much cashflow they have had to give up to reduce the debt,” said Chanos at Kynikos. “People haven’t yet begun to focus on the reduced income as a result of that. That is still ahead of us.”