Quantitative easing was once a highly lucrative business for central banks. Huge asset purchases, often made during periods of market stress when bond prices were low and yields high, enabled some institutions to lock in steady and substantial income streams.

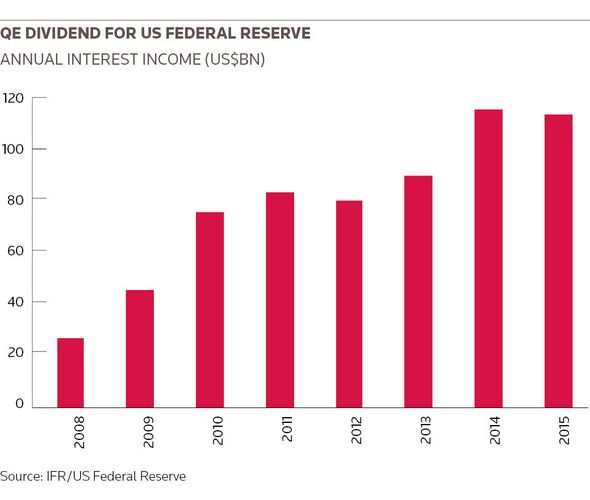

The US Federal Reserve has been the biggest beneficiary. Its QE programmes ended almost two years ago, yet the purchases it made continue to generate huge revenues. Last year alone, the Fed earned US$114bn in interest on previous asset purchases, bringing its QE-related income since 2008 to over US$634bn.

The Bank of England and Swiss National Bank are also reaping the benefits of QE, with the former booking £14bn in coupon payments in the latest fiscal year to March. With most central banks transferring profits on to their respective governments, QE has substantially boosted government revenues over the past few years.

But the latest round of QE programmes are unlikely to deliver such dividends. Think tank Bruegel estimates the European Central Bank and its 19 national central banks will collectively earn an “almost negligible” amount from the sovereign bond purchases that began in March 2015 – it sees just €4bn of income over the first 19 months.

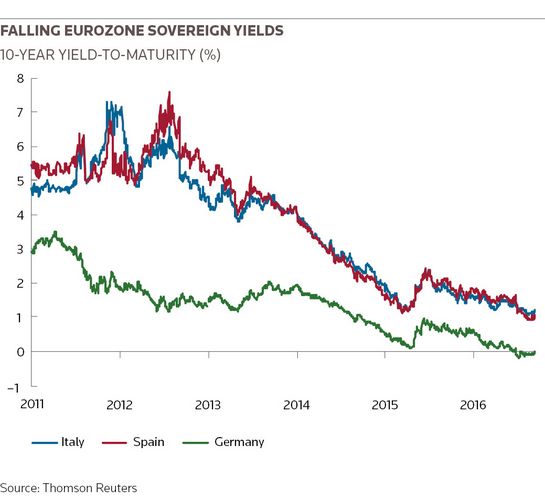

The fall in European sovereign yields, a running trend that pre-dated ECB QE, is to blame. Spanish 10-year bond yields, which peaked at 7.6% just four years ago, are now trading below 1%. Many eurozone government bonds yield close to zero, while the German yield curve is actually negative out to 10 years.

“There is no escaping the fact that any potential profits will be far lower for the ECB,” said Frederik Ducrozet, a senior economist at Pictet. “Their starting point was very different to the QE programmes of other central banks. Rates are lower, yields are lower, there is less debt being issued each year.”

Simmering tensions

A lower QE dividend will not be of too much concern to the ECB board: after all, the rationale for doing the programme isn’t to make money, rather to jolt the eurozone economy into life. But the way that QE is set up and the way the QE dividend is spread could add to already simmering tensions between the ECB and the 19 eurozone national central banks.

The NCBs are the main buyers of bonds, tasked with purchasing 92% of the €80bn monthly QE target. Normally, the NCBs share out income from their asset purchases to ensure no one benefits disproportionately. But this time, they have chosen to forgo that sharing – at least for sovereign purchases. NCBs can keep all their income.

“It is a potential concern for some of the NCBs but they have to carry on with the programme”

Complicating matters further, all NCBs are restricted to only buying their own domestic sovereign bonds: so the Deutsche Bundesbank is forced to buy mostly negative-yielding bonds, while Banco de Portugal can buy 30-year paper yielding almost 4%. The potential for earnings, which are no longer shared, is vastly different.

“Some banks, including the Bundesbank, didn’t want to be liable for any potential losses that might arise out of the sovereign portfolio from a future default, and so the different potential for income or losses is a natural consequence of that,” said Ducrozet. “It is a potential concern for some of the NCBs but they have to carry on with the programme.”

Annual NCB accounts already show how QE is impacting their P&L in very different ways. The Bundesbank had negative income of €11m on its sovereign purchases last year. By contrast, the Banco de España and the Banca d’Italia both booked more than €350m.

So far, of the 19 only the Bundesbank has reported negative income from its sovereign purchases. But the hit comes at a time when the German central bank, which has always been hesitant about the merits of QE, has seen a large decline in other sources of income. It earned €3.3bn in interest income last year, down from €11bn in 2012.

With some substantial sources of income – interest from its holdings linked to the securities markets programme launched in 2010 amounted to €1.7bn last year alone – set to fall dramatically, losses from sovereign purchases may soon become more of an issue.

Insiders at the Bundesbank say that negative income isn’t an issue for the bank – but could be if the ECB removes the current –0.4% floor on minimum yields that can be bought. It also pointed to the extra income – €248m – the bank has gained from having a negative deposit rate.

Negative equity

Central bank losses have long generated debate in the academic community. Gregory Claeys, a research fellow at Bruegel, said the Bank of Chile ran its accounts for many years with negative equity. “P&L is meaningless, central banks are not commercial banks,” he said. “Even with negative equity you won’t go bankrupt.”

Still, not all NCBs are comfortable with the idea of losses. De Nederlandsche Bank has already begun making provisions – €500m last year – against future losses. “The Dutch want to make provisions to avoid making a loss in the future,” said Claeys. “Perhaps they are concerned a loss might lose them some credibility with the public.”

But with inflation continually missing the ECB’s target, economic growth sluggish at best and the unemployment rate still in double figures, the central bank and its 19 NCBs may have little choice but to continue on this path – even if it means losses for some. The greater good may necessitate those costs.

“The NCBs take their share of the risk and they get their share of the spoils – the profits,” said Marchel Alexandrovich, senior European economist at Jefferies. “Even if some of the banks lose money on this, it doesn’t really change things – it is just part and parcel of their effort to boost the wider economy, which comes with various costs.”