The Greek effect – Turkey’s unprecedented stability has turned it into a magnet for investors – but it is in a rough neighbourhood and political risk is likely to creep up the agenda this year.

To view the digial version of this report, please click here.

At first sight Turkey could be sitting at the eye of a storm, having to deal solely with the enviable problem of an economy prone to growing too fast as turbulence swirls all around.

That is certainly how Turkish business figures and outside observers see it, dismissing the crisis in neighbouring Greece, nausea in the eurozone, the prospect of a bust-up with the EU over Cyprus, and growing regional tensions stoked by Syria, Iraq and Iran.

It is hardly surprising that the president of the Turkish Exporters Assembly (TİM) Mehmet Büyükeksi recently portrayed 2012 as a “safe journey on a stormy sea”.

However, despite unprecedented domestic stability buoying investor sentiment, this is set to be a defining year for Ankara’s foreign policy.

Turkey’s location potentially allows investors to access multiple markets in Europe, MENA and the Caucasus. But in a climate of risk aversion its structural weaknesses – lack of savings and currency reserves and a reliance on foreign energy and trade – leave it exposed.

Investors are trying to shake off last year’s frustrations at what they saw as fumbling by the central bank over the country’s deficit and currency policy, yet macro imbalances remain and questions persist about the sustainability of Turkish growth on the back of domestic credit.

Eurozone benefits?

While most observers believe that, far from being a loser from eurozone and Greek troubles, Turkey could be a significant beneficiary, Europe’s problems will not leave the banking system unscathed: more than 70% of of syndicated loans in the Turkish banking system are from European banks.

Senem Başyurt, executive director of Transaction Advisory Services M&A Advisory at Ernst & Young said: “Any kind of slowdown in these economies has a direct impact on export growth. Moreover, the traditional source of FDI to Turkey has been the European countries. Given that the financing sources are limited, we can expect a slowdown in investments and/or capital injection from the eurozone.”

Yet Basyurt believes that because the main trading partners of Turkey are stronger countries like Germany and France, the impact both on exports and FDI will be limited.

Turkish trade is booming, up 18.5% in 2011 on the previous year and in February [2012] hit US$11.2bn, according to TİM. There are, nonetheless, signs that trade with the EU has slipped, with Europe’s share of the Turkish export market falling to 43.5% in January [2012] compared with 47.7% in January 2011 (see table).

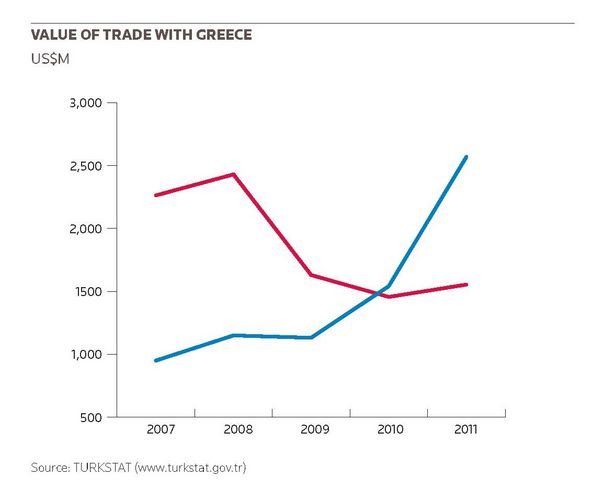

Potentially, Greece’s vast debt and long-term stagnation could further slow development in the region – but Turkey’s relationship with Greece remains limited and trade has not been hit dramatically: TİM and Eurostat figures suggest Greek imports from Turkey held up at €1.18bn in 2011 compared with €1.17bn in 2010.

Ozgur Altug, chief economist research at BGC Partners, said that while the eurozone crisis definitely affected Turkey, Greece is a non-issue: “When we look at exports, imports, tourism and other macro data, Greece’s contribution to the Turkish economy is very limited.”

About 480–500 Greek companies operate in the country, although banking and finance comprise more than 80% of Greek capital investment. Business figures say Greece’s drastic privatisation programme to 2017 represents an unmissable chance for Turkish investors: Athens has promised to sell €50bn of assets and put its state-owned gas company DEPA on sale last month. On March 22 Turkey’s Deputy Prime Minister Ali Babacan added to the momentum by reportedly telling a meeting in Istanbul that the only formula that will “save Greece’s future” is more trade and investment with Turkey.

Investing in Greece

The best method for Turks to invest in Greece will be through partnerships, and M&A experts have argued that hefty discounts will open doors.

Basyurt said: “We know that some Turkish companies are considering investments in Greece and looking for opportunities with good business cases but experiencing liquidity problems. Especially, export-oriented manufacturing companies look to leverage the EU connection – this is critical in sectors such as food where there are strict import restrictions to the EU.”

Turkish banks may also be inclined to discuss mergers, and energy is another key area of potential development, with Greece and Turkey already partners in the ITGI (Interconnector Turkey-Greece-Italy) pipeline to be fully operational by 2015, and Turkey’s state-owned BOTAŞ pipeline company thought to be interested in DEPA shares.

The mood music of bilateral exchanges has also stressed co-operation. Turkish entrepreneur Erol User, CEO and president of User Corporation, said: “Businessmen and the Turkish government have shared their experiences from the 2001 financial crisis in an attempt to point out some harsh lessons learned on their own economic front… There is a great potential for Turkish investment in Greece.”

However, deep underlying tensions persist that heighten investment risks.

Tensions

Greek-Turkish relations remain strained and in February, Thanos Dokos, director general of the Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy, warned that analysts had unrealistically ignored the geopolitical dimensions of the Greek crisis. Moreover, Greece is the main interlocutor of the EU’s relationship with Turkey, which remains complicated by Cyprus and, recently, a row with France over interpretations of the 1915 Armenian killings.

Perceived wisdom is that Greek profligacy has been at the root of its woes, but many Greeks themselves believe that the burden of defence spending – made necessary by Turkey’s position on Cyprus – has been a major cause of Athens’ problems. Under the terms of the latest bailout, Greece will slash defence spending by €400m, changing an uneasy equilibrium that has prevailed for 38 years.

A key turning point that will set the tone for Turkey’s future relationship with Europe will come in July when the Greek Cypriot government is due to take on the six-month rotating EU presidency. Turkey has said it will freeze relations if this occurs

Greece and Turkey have other disagreements and press reports suggest there is little appetite within Greek society for Turkish investment. Başyurt said: “We know some Turkish groups are interested in privatisation, but they have considered this area to be a hard case for investors from Turkey due to sensitivities of the Greek public, and withdrawn interest.”

Other issues will shape the investment climate: the Arab Spring, fears about Iraq fragmenting, border tensions with Syria, a stand-off between Iran and the West, and a deterioration in relations with Israel.

So far, the Arab Spring has not hit exports, stability in Iraq generated a 38% increase in imports from Turkey in 2011, and sanctions against Iran also pushed up imports by 18%. Iranian companies are setting up at a rate of knots in Turkey, and large Turkish acquisitions in 2011 included the purchase of Iranian company Razi Petrochemicals by Asya Gaz Enerji.

But while investors do not price in geopolitical risk until events happen and it would seem safe to conclude Turkey is enjoying “safe journey on a stormy sea”, vigilance seems wise.