Though lambasted for being the primary cause of the financial crisis, securitisation technology has proved its worth in providing a variety of institutions and state entities with funding using a range of cashflows to support their transactions.

To view the digital version of this report, please click here.

Dubai became the latest example with a toll road fee-backed deal, and while there is potential for further issuance from the Middle East, hurdles still remain.

European issuers have been able to rely on RMBS and auto loan ABS, confident of well-worn paths and proven track records in each specific line, but for the atypical countries of issuance, the situation has proved far more troublesome.

But off-the-run secured transactions such as the US$800m Salik toll road receivables deals on behalf of the Road Traffic Authority (RTA) to fund future infrastructure projects in Dubai prove there is life in the market yet. The six-year issue closed in July through Citigroup, Commercial Bank of Dubai, Dubai Islamic Bank and Emirates NBD.

Commenting in a press release at the time of closing, Matthew Job, capital markets partner at Herbert Smith said: “The transaction is notable because although it is a bank-funded structure it incorporates some receivables-based technology usually found in securitisation deals, and because it contains both conventional and Islamic tranches.”

Essentially, this project started out in the banking market but adopted an ABS strategy.

“In borrowing the funds RTA needed to provide some security, this ultimately was the future flow of toll road revenues,” explained Debashis Dey, partner at Clifford Chance.

The Salik toll road system, named after the Arabic word meaning “open” or “clear”, launched in July 2007 as an automated tolling system charging road users Dh4 per gate they pass through.

Despite the relatively low charge per toll gate (a little more than one US dollar equivalent), it has sufficient use for the cashflow to be considered strong enough to secure this transaction. It could, therefore, set the tone for receivables-backed funding projects in the future.

Outlining some of the reasons why, one lawyer said: “Taking into account the heat, everyone uses cars. There is an utterly robust traffic forecast, based on steady and persistent traffic”, which provides exactly the kind of stability of cashflow that a secured issue requires in order to under-pin investor confidence. This is in contrast to Europe where deals have not performed in line with expectations, he said.

From the value point of view, the asset “has to be an issuer pay arrangement raising money from the population and not the state. Any issuer pay arrangement with genuine robustness to cashflow would fit the bill”, he added.

Potential grows

As far as issuance growth is concerned, secured financing strategies could be employed using a variety of assets. Salim Nathoo, partner at Allen & Overy, referred to real estate lease receivables and possibly more auto deals, although a steady supply of auto loans receivables in Dubai is hindered given the limited population of the emirate at around two million.

Dey listed a number of potential future flow revenue suppliers including the use of infrastructure elements such as oil and gas costs, airport and transport usage fees as well as real estate leases in Dubai.

And for other countries, such as Qatar, gas revenues were also a consideration to harness a technique such as Salik, he said.

Despite the potential elsewhere, Dubai may actually remain the biggest advocate of securitisation technology in the Gulf Cooperation Council region simply due to its lack of access to a major asset – oil.

“Other GCC sovereigns don’t necessarily need the money as much as Dubai does because of the availability of oil revenues,” said Nathoo.

He added that other countries considering external borrowing could benefit from monetising assets. But while the potential for secured financing is clear, it is likely that such decisions will vary between GCC countries.

“Each country has its own future infrastructure needs but will not want to commit large amounts from their oil reserves to exclusively fund this development,” Dey explained.

There are other issues that need to be factored in regarding the options available to GCC issuers.

“Securitisation in the GCC region is competing against a liquid bank market, but it can offer longer-dated amortising funding and diversity of investors,” Nathoo added.

Working against pure securitisation is the cost associated with it. “Pricing can be more expensive [than the bank market] due to structuring issues, such as registration costs and moving assets into SPVs. Some deals have been pulled due to cheaper funding in the bank market,” Nathoo noted.

And so the optimism does come with a sense of caution, but one that may be overcome.

“It is an attractive proposition in certain circumstances but the legal and regulatory environment for securitisation needs work in some GCC countries,” Nathoo noted.

What external, secured funding can do, more specifically for Dubai than its neighbours, is ease its looming debt redemption schedule.

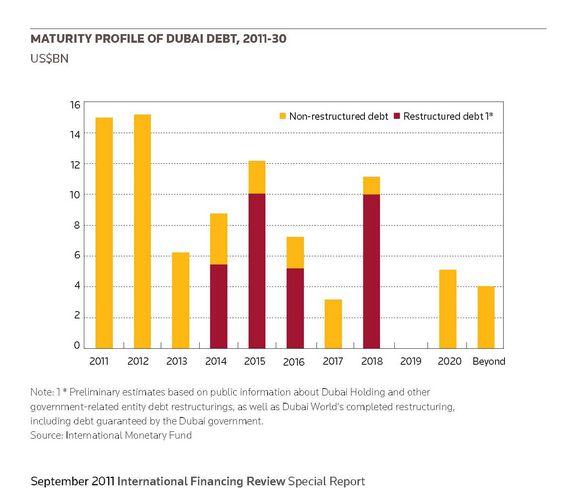

According to “United Arab Emirates: Selected Issues and Statistical Appendix” published by the IMF in May 2011, Dubai has around US$31.2bn of debt due in 2011 and 2012.

As a result, options must be sought to relieve this debt burden which already takes into consideration substantial restructurings for Dubai World and Dubai Holding.

Reprise of real estate?

While securitisation in the European sense of the term, through the true sale of assets to a limited recourse SPV, may not be commonplace in the GCC region, some assets do lend themselves to secured financing techniques. As alluded to above, real estate is one such contender and could provide vital funding, and not just for the government.

“The real estate sector has significant issues. There are a number of corporate developers struggling to obtain funding and so there could be a willingness to do commercial lending arrangements using the income from leased assets to secure a deal,” Dey explained.

A number of Dubai real estate deals were carried out in the years running up to and just after the crisis, but plummeting asset values hit the sector hard while the Nakheel/Dubai World funding problems undermined investor confidence.

But there may be hope yet as the Dubai economy recovers and various initiatives have been implemented to boost demand in the region, such as property investors being granted a three year residency visa.

Existing deals have bounced back from rating downgrades too, an example being Tamweel Residential ABS C1. On August 1 Fitch raised three classes of notes by one notch, citing “the stabilising performance of the Dubai property market” in addition to the upgrade of servicer Tamweel.

The upgrade was due in part to a turnaround in performance of the lease originator, as well as the Dubai Islamic Bank’s acquisition of a controlling interest stabilising the company.

“Securitisation in the GCC region is competing against a liquid bank market, but it can offer longer-dated amortising funding and diversity of investors”

Tamweel returned to profitability in 2010 due to declining provisions and improved funding costs and even resumed lending in the first quarter of 2011 after a two year hiatus as an indication of tentative growth in the real estate segment.

According to Jones Lang Lasalle’s Q2 2011 Dubai Real Estate Market Overview, the investment market continues to be dominated by private rather than institutional investors, while the firm’s investor sentiment survey confirmed more buyers than sellers.

This outstripping of supply by demand should support property prices, but the number of transactions completed has not benefited due to a lack of high quality assets with strong tenant covenants, the firm said.

And high vacancy rates remain an obstacle to lease rental income as a source of security for new bond issues. According to Jones Lang Lasalle, vacancies remained unchanged at 44% city-wide versus the first quarter and 27% in the Central Business District.

Prime office rents have been steady at Dh1,165 per square metre, but this is still only around a quarter of the Dh4,306 commanded in the fourth quarter of 2008. The report also warns that declines are anticipated once new supply hits the market later this year and city-wide vacancies could top 50% in 2012.

Switching to residential property, most of this segment has experienced sale price and rental decline as landlords become more lenient with their rates. The hotel and retail mall sectors are expected to be stable over the next few months, however.

But while the real estate sector still lags behind other segments in the economy, it is at least recovering slowly. For example, real estate grew by 2.6% in value in 2010 following a substantial 19.8% decline in 2009, according to the report.

This slight growth is a step in the right direction but, property portfolio valuations still have some way to go return to the pre-crisis levels and to exhibit the kind of stability that investors rely on.

And given that Dubai cannot call on oil-related products as its neighbours, secured products from these areas could have a very important role to play in its financing outlook.

But whether it is through pure securitisation, or in the mould of a Salik-style project initiated in the bank lending market before evolving into a secured capital market deal backed by asset cashflow, remains to be seen.