China’s new AIIB multilateral bank is a symbol of a bold new foreign policy that places the country in a position to lead the next round of globalisation.

A favourite phrase of the great Chinese patriarch Deng Xiaoping encapsulating his approach to foreign policy was: “Hide your brilliance, and bide your time.”

The underlying idea was that the rapidly growing Asian dragon needed to proceed in diplomatic affairs in a way that did not frighten the rest of the world, whose investment, technology and markets it needed.

No better symbol exists of how this cautious approach has been superseded by the country’s paramount leader Xi Jinping than the creation of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which was announced in 2013 and is now taking form on paper.

Jonathan Fenby, managing director of China research at emerging market research service Trusted Sources, said: “There has been a real sea change in foreign policy under Xi Jinping, who took power 2-1/2 years ago, which can be summed up in the phrase ‘We are going to show our brilliance, and our time has come’, and the AIIB is part of that. What this reflects is geopolitics being backed by geo-economics.”

Geopolitical ambitions

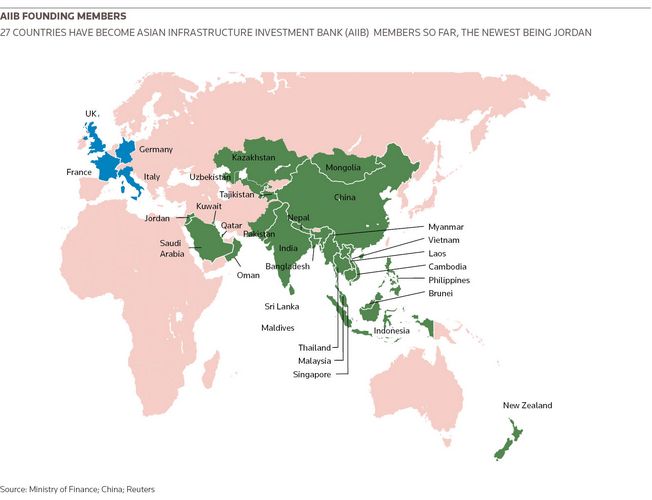

Borne out of frustration with a lack of reform at US-led multilateral financial institutions such as the World Bank, International Monetary Fund and Asian Development Bank, the AIIB now has 57 prospective founding members and is likely to have registered capital of at least US$100bn, against which it can borrow a multiple from capital markets.

On paper, its aim is to fund infrastructure – with a key focus to finance China’s ambitious vision of a “New Silk Road” – but Fenby believes the creation of the bank cannot be divorced from Beijing’s broader geopolitical ambitions, using “strategic economic” tools backed by eye-watering reserves of US$4trn rather than the “strategic military” approach of the past.

In particular, the creation of the AIIB responds to the desire both to export excess capacity at a time of slowing growth in China itself and to internationalise the renminbi.

“China has invested heavily in infrastructure, so much that it now has a lot more buildings and structures than it can use – there are roads that lead nowhere and cities that no one is living in,” said Danae Kyriakopoulou, senior economist at the Centre for Economics and Business Research.

“This means that returns to further investment domestically are not promising, and so China is looking abroad for higher returns and ways to keep its infrastructure industries in employment. This is an important motivation for creating the AIIB.”

Meeting a need

Yet Asia’s financing needs for infrastructure are well beyond the capacity of existing institutions. The ADB Institute estimated in 2010 that infrastructure needs in the region in order to sustain growth would amount to US$8trn up to 2020. The ADB, with registered capital of US$165bn, still finances less than 2% of Asia’s needs.

Frederic Neumann, co-head of Asian economics research at HSBC, believes emerging Asia will need to invest more than US$11trn in infrastructure from now until 2030, with the majority required outside of China.

He wrote in the Nikkei Asian Review: “The existing arrangements are not up to the scale of the challenge. Despite Asia’s success in driving growth, hundreds of millions of people still live near the poverty line. Demographic trends suggest the pressure on government budgets will only grow over time.”

Nonetheless, behind the hype and high expectations surrounding the creation of the AIIB, it is clearly too soon to assess its prospects.

Nahed Ennasr, chief strategist at Fathom Consulting, said: “It’s far too early and very difficult to judge if the AIIB will have any benefits for Asian countries. Our first conclusion is that China is trying to export its overcapacity and it is unclear if AIIB will have any sort of influence in the region.”

Currency ambitions

She agrees that its creation has to be seen alongside China’s broader ambitions for its currency, though it remains undecided which currency the AIIB will use – the US dollar or renminbi, or a mixture of both. Much will depend on what happens at the IMF, which in May began debating whether the renminbi should be incorporated into its Special Drawing Rights, a matter over which the US does not have a veto.

China’s currency ambitions help to explain why countries such as the UK, eager to become an offshore centre for renminbi settling, have rushed to join the AIIB. According to HSBC, the offshore renminbi market now represents 14% of non-G4 (that is, the G3 currencies plus sterling) international bond issuance.

While a key but not exclusive focus of the AIIB will be the New Silk Road initiative, much of the attention so far concerns the bank’s implications for established geopolitical norms.

Thinly veiled US hostility to the creation of the AIIB was in evidence earlier this year when Washington voiced public fears about the possibility of lax standards at the new lender and was unable to contain its criticism of the decision by the UK to join the Chinese-led multilateral, followed in short order by Germany, France and Italy.

US opposition to the AIIB has been dismissed as insecurity about its global influence, and it remains too soon to determine whether concerns about standards are justified.

Fenby of Trusted Sources believes that in raising the issue of standards publicly, Washington has almost certainly ensured that this will not be a problem.

“The Chinese want this to be a success, obviously, and they would avoid any lowering of standards that would lead to, let’s say, some of the Europeans leaving or expressing reservations. That would be embarrassing for China and they will want this institution to operate as transparently and to the highest standards as possible,” said Fenby.

The AIIB has also won significant support in other quarters, with the IMF, World Bank and influential development economists such as Joseph Stiglitz welcoming the announcement.

There is little doubt the new institution will have implications for the ADB, a frequent target of criticism for dragging its feet and imposing overly-stringent requirements on projects. There may also be implications for the New Development Bank, the BRICS bank launched by China with Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa and due to start lending in 2016.

Kyriakopoulou of the CEBR said: “The Japan and US-led ADB quickly rushed to defend their territory by making plans to increase their own infrastructure spending and investment and loans to Asian countries – this suggests a tension with the AIIB even though it has not been explicitly expressed as such.

“But this ‘duplication’ is not necessarily a bad thing – there is plenty of room for both competitors. The Asian financial crisis has left a deep legacy of an infrastructure deficit in the region and heavy investment is needed to overcome this.”

Mutually beneficial

In principle, there is no reason why the AIIB cannot operate in a landscape in which multilaterals complement each other, as occurs within Latin America. However, crucial governance questions have yet to be answered, points out Ennasr of Fathom Consulting.

“When you dig a little deeper, it seems that there has been a lot of talk for something that is not set up yet, because the operating framework of the AIIB has not yet been established,” she says. “Yes, 57 members have signed up and they have set a budget, but there is no governance framework and it is also unclear which currency they will be using, how are they going to meet international standards, and how they will allocate the voting.”

Ennasr believes one sticking point could be the conditionality placed on AIIB loans, given China’s record in regions such as Latin America where lending was often tied to the use of Chinese companies and workers.

Potentially, there is also likely to be tension between the developmental agenda embodied in the AIIB and China’s broader geopolitical ambition in the South China Sea. Russia’s response to the Silk Road strategy remains an unanswered question.

Fenby of Trusted Sources believes that, while China is unlikely to use the AIIB in an overtly political way as a blunt instrument with which to get its way, “I would be very surprised if the AIIB did anything that China did not approve of”.

Crucially, if Beijing is the largest shareholder in the AIIB – most estimates suggest it is likely to hold between 25% and 30% of the shares – then there will be attention paid to the potential impact of economic problems in China on the multilateral bank.

This intimate relationship with China’s economic fate means that, as a symbol of the country’s newly assertive role on the world stage, there is little doubt the stakes are too high for Beijing to allow the AIIB to be unsuccessful.

Fenby said: “China has to make it succeed. It can’t allow this to fail. If it is going to push for greater internationalisation, it becomes a geopolitical priority, because if the AIIB didn’t work or if its standards were too low or skewed, it would be quite a big setback for what is a much more cohesive, coherent foreign policy under Xi Jinping.”

To see the digital version of this report, please click here

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email gloria.balbastro@thomsonreuters.com