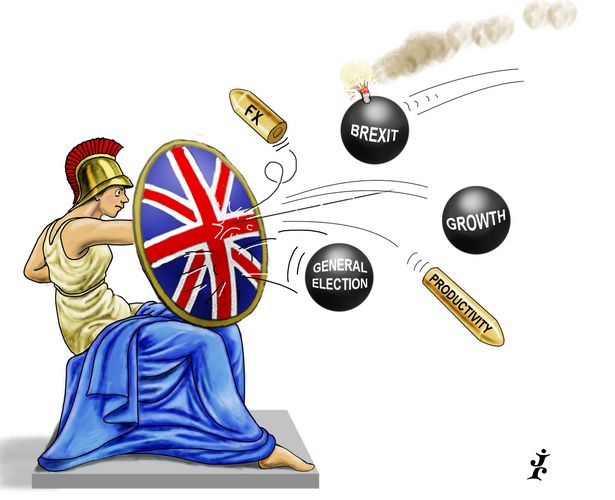

Strong and stable

Difficult negotiations to leave the EU, a snap general election that led to a minority government, continuing volatility in sterling and the first interest rate rise in a decade all failed to knock the UK issuance bodies off their feet. Debt issues were remarkably unaffected, while the government finally disposed of its last shares in Lloyds Banking Group. The United Kingdom is IFR’s SSAR Issuer of the Year.

When it came to managing borrowing for the United Kingdom, nothing got in the way of the Debt Management Office, not even a tumultuous political backdrop. It was with a remarkably steady hand that the DMO remained on course to raise £114.2bn for its 2017/18 fiscal year.

Prime Minister Theresa May’s decision in April to call a snap general election aimed at strengthening her position ahead of the Brexit negotiations caught markets unaware and wild gyrations in the pound followed.

Yet with less than a month to go before the June 8 poll, the UK DMO began its syndicated programme for the fiscal year with a £5bn tap of its 1.75% July 2057 Gilt that attracted what was at the time the largest-ever nominal and cash order book at £24.6bn.

“We try to ensure that we continue regardless of political noise and do not let ourselves be deflected by it. It’s not helpful to the programme, it’s not helpful to the Treasury if we let ourselves be influenced by that political noise,” said Robert Stheeman, chief executive of the DMO.

“The market understands that, and understands how we operate. We bang on about the importance of being predictable and transparent. It is reassuring for the market to know that we stick to a tried-and-tested model of engaging with the market, of planning issuance well in advance.”

And if the political noise was not enough, the DMO had to deal with a one-notch downgrade by Moody’s to Aa2 on September 22.

The agency, which stripped the UK of its AAA rating in 2013, cited significantly weakened public finances as well as fiscal pressures.

And yet, it was business as usual when the DMO brought a £3bn tap of its 0.125% 2048 index-linked Treasury Gilt, which managed to beat the record set by the £5bn 2057 tap, receiving £25bn of demand, now the DMO’s largest order book in cash terms.

That trade marked its fourth syndication of the fiscal year, taking to £19.9bn the proceeds raised via that method, just £2.9bn short of the £22.8bn minimum it committed to raise through syndications.

The last syndication for an index-linked Gilt is scheduled to take place in the first quarter of 2018.

HOME AND AWAY

Fostering a supportive domestic investor base has been one of the key aspects to the DMO’s success, with its syndications finding a comfortable home with locals.

This is especially true of the long and ultra-long end, where pension funds and life insurance companies dominate the market.

“We wouldn’t want to take it for granted. If you look at the share of the yield curve, it tails off between 30 and 50 years and that’s all down to our domestic investor base and the demand they provide,” said Stheeman.

“That has been a huge support for us and the issuance programme. They’ve been dominant for a generation and helped the UK finance itself at the long end at attractive levels.”

Overseas investors, which hold 27% of the Gilt market, have also proven to be reliable even in more volatile times.

Listening to the needs of its Gilt-edged market-makers – aka GEMMs – has allowed the DMO to keep them on board, not an easy task in the days of stretched balance sheets for investment banks and where some European DMOs have seen support ebb.

“We are trying to make life a little easier for our primary dealers,” said Stheeman. “This is an acknowledgement on our part that we need functioning GEMMs that support our issuance programme.”

The DMO introduced a number of changes to its issuance programme in 2016, such as marginally reducing the size of its auctions but making them more frequent.

This has given a bit more breathing room to banks that did not always have enough capacity to take down and warehouse risk.

BATTENING DOWN THE HATCHES

The Teflon-like qualities of the UK market are not to be taken for granted, however. Tensions around Brexit and a darkening economic outlook might mean that the era of ultra-low yields and smooth sailing is drawing to a close.

“A rising yield environment will of course increase borrowing costs, but it’s a natural part of the cycle,” said Stheeman.

“As long as that upward movement in yields is not accompanied by unhealthy volatility and the market adjusts to find a new clearing level, that is the market doing what it is supposed to do: to find the right price to be able to take down our supply.”

The DMO will also have to navigate changes that are likely to accompany the shift in the Bank of England’s monetary policy.

While expectations are that the first rate hike in more than a decade is unlikely to be followed by a dramatic tightening in monetary policy, it is still a change.

Furthermore, the Bank of England has so far also been quiet on what it plans to do with the over £472bn of Gilts it held as of the second quarter of 2017.

MINIMAL FUSS

While the DMO caught headlines with its activity, UK Financial Investments, the body that manages holdings the government acquired during the financial crisis, managed to sell a huge stake in Lloyds Banking Group with minimal fanfare thanks to the use of a dribble-out programme run by Morgan Stanley that raised more than £13bn from the sale of 24.9% of the bank.

The first dribble-out began in December 2014 and ran to June 2016. When the government abandoned plans for a retail offer of the remaining stake of 9.2% a second trading plan was introduced, again run by Morgan Stanley, that began in October 2016 and ended with the disposal of the last shares in May.

The UK government’s choice of dribble-out meant it was able to dispose of a huge stake by selling to natural buyers in the market with no discount and without disrupting the share price. It also gets around the predictability of when large accelerated bookbuilds may happen due to the blackouts created by bank results and government activity. As a strategy it is hard to pick holes in, and while UKFI’s mandate is entirely economic, that is attractive for the politicians giving the go-ahead.

Progress was also made on the RMBS take-outs of Bradford & Bingley buy-to-let mortgages held by UK Asset Resolution, which is managed by UKFI. In April, Harben Finance and Ripon Mortgages were placed, having previously been owned by UKAR. The government vehicle used stapled financing to remove execution risk and therefore achieve a higher price from the sale.

The earlier sale of the Granite portfolio of Northern Rock mortgages at the end of 2015 had been deemed a success, but politicians were later critical of pricing. Maximising value was important and senior notes on both RMBS deals priced above par.

A modified auction-style process was used to manage the publicly offered Class E and F notes on Harben to get the best possible price. The other Classes A–D were pre-placed.

On Ripon, distribution was a mirror image with Classes A–D offered publicly and E and F pre-placed and pricing on the Class A notes at 80bp over Libor was significantly tighter than the 85bp guidance.

To see the digital version of this review, please click here.

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this review, please email gloria.balbastro@tr.com.