The weakness in the oil market, relative to the highs enjoyed in past years, has provided a supportive backdrop for Islamic bonds, forcing oil-rich Middle Eastern issuers to fund in the market. The market’s outlook will be determined in large part by oil’s future path, though investors will also be looking for assurances that Middle Eastern issuers honour their legal obligations.

The fall in the price of oil in recent years has been a game-changer for Islamic bonds, tilting issuance towards the Middle Eastern countries that have traditionally had little need for debt financing. Whether these issuers remain in the market once the oil price recovers remains to be seen, but most expect they will be active again in 2018, at least.

Patrick Drum, portfolio manager at the Amana Participation Fund, which invests primarily in Islamic debt, principally sukuk, said: “The fall in the price of oil has created a real opportunity. The region’s hydrocarbon financing model is broken and sukuk can step in to allow Middle Eastern sovereigns to offset their deficit funding. We are talking about countries with a solid investment-grade status such as Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Qatar, which will appeal to a lot of investors.”

The year saw US$27bn of international sukuk issuance to November, around US$6bn more than was issued in the same period in 2016 and nearly US$2.5bn more than was achieved in the whole of that year.

Sovereigns and public-sector bodies have driven this issuance. In January, Investment Corporation of Dubai issued US$1bn of 10-year sukuk, before a Saudi dual-tranche US$9bn offering in April became the largest sukuk transaction ever sold. In May, Oman easily raised US$2bn with a seven-year issue, while Bahrain raised US$850m via sukuk in September as part of a broader US$3bn three-tranche financing.

Usman Ahmed, head of Citigroup’s Islamic bank in Bahrain, said: “I expect to see growth in the sukuk market continue during next year. A significant portion of capital markets activity from the MENA region will continue to come in sukuk format, driven by investor appetite.”

PAYMENTS HALTED

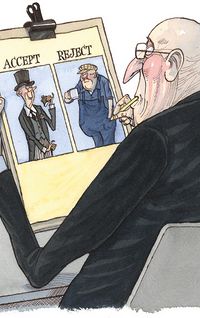

The year has not all been plain sailing, however. Storm clouds gathered on the horizon in June when Sharjah-based issuer Dana Gas announced it would halt payments on two US$350m sukuk issues, citing changes in the interpretation of Islamic scholars that it argued rendered their structure non-compliant.

This news, and the proposed restructuring that resulted, dealt a significant reputational blow to the sukuk market, leaving investors wondering whether other deals could be similarly affected.

That is unlikely: the issues around the Dana Gas sukuk were unique to the UAE Civil Law Code, which must apply to all mudaraba structures under UAE law. Observers say this code does not even apply to all sukuk in the UAE, let alone elsewhere, making the legal uncertainty around the Dana Gas deal largely irrelevant to the broader market.

Investors apparently agree, with a number of issues having completed – and being well received – since the dispute started and a number more roadshowing at the time of writing.

In November, London High Court judge George Leggatt ruled in favour of the creditors, demanding that Dana Gas repay the US$700m of bonds, providing further comfort, and a separate court hearing will take place in Sharjah to determine whether the mudaraba structure is valid under UAE law. In other words, the two hearings are about different things, which complicates matters, as does the fact that Dana has said it will appeal against the English court ruling.

Drum said: “Justice Leggatt’s ruling with Dana has provided the legal proceeding to protect investors’ interests but this case is unfolding and Dana’s response to the judgment will have important implications for investors and issuers for some time to come. The ruling needs to be upheld; if it is, this could actually prove to be a catalyst for further growth in the market.”

The problem with Dana Gas was first and foremost a credit issue, said Drum. “It was clearly high risk, it has had issues in the past, including a restructuring in May 2013, and it operates in countries with challenging economies. Dana’s behaviour is highly disingenuous, but it is not fatal for the broader market.”

If GCC countries are serious about this market, they need to act with consistency and integrity to ensure the continued interest of foreign investors, Drum added.

Obiyathulla Ismath Bacha, a professor specialising in finance and accounting at the Global University of Islamic Finance (Incief) in Malaysia, said the case demonstrates the need for standardisation across the whole market.

“We can’t have individual sharia committees deciding what is or isn’t compliant, we need clear, transparent rules, akin to IFRS, so it is clear to everyone what does or does not qualify,” he said. “Otherwise you can have this kind of situation where a sharia committee can change its opinion. Because if it can happen in the case of Dana Gas, it can happen with any deal.”

DARE TO BE DIFFERENT?

Despite the popularity of sukuk, Bacha believes Islamic financiers should do more to distinguish the market from that of traditional bonds.

“The problem Islamic finance has at the moment is the focus is on imitation rather than innovation. It is about creating Islamic versions of the products seen in the West, when it should be looking to differentiate itself. It is increasingly difficult to see the difference between an Islamic bank and a commercial bank, they have mimicked the products and the processes,” said Bacha.

“They have even mimicked the regulation, given Islamic banks follow Basel-like rules, which mean that risk-sharing financing like mudaraba and musharaka are penalised with higher capital requirements. The market operates on the same rails and therefore it goes in the same direction,” he added.

The result, said Bacha, is a slowdown in the growth of Islamic financing generally. And the solution, he argued, is a push to promote structures that offer a real alternative to the West’s traditional debt model.

“To achieve the next stage of growth the market needs to truly innovate by focusing on its strengths, which is risk-sharing and profit-sharing products like musharaka that avoid leverage and debt,” Bacha said. “Instead, Islamic finance is creating sharia-compliant debt, which exposes it to the same vulnerabilities as other forms of financing.

“What is the point in an Islamic bond if it references Libor, because there is no Islamic equivalent? Why would an investor bother with the extra hassle if the product is really no different? But banks are more comfortable with what they are doing than developing these new kinds of products like musharaka.”

While such products may well find favour among Muslim investors, they would be unlikely to appeal to international investors. “Islamic issuers need to appeal to different types of investors, so it is natural that they focus on sukuk that look like traditional bonds,” Drum said. “That is how they grow this market.”

Defending banks’ strategies in Islamic finance, Ahmed said: “Customers who want sharia compliance still expect the same economic benefits as those offered by conventional products. So it’s our job to deliver the same level of service and the same functionality across our conventional and Islamic banking offerings.”

There can be a slightly higher initial cost for sharia products, he admitted, but there would have been a similar initial cost when creating the first ISDA document or any other new product. “Once that investment has been made, for example with a sukuk MTN programme, issuers can tap the programme quickly and in a cost-effective manner as often as they require, the same way as for a conventional MTN programme.”

Bacha admitted it will take a significant event to alter this mindset. “If we are going to see real innovation in the Islamic market, with new products developed along the lines of musharaka, we may unfortunately have little choice but wait to see a sharia-compliant debt crisis,” he said. “Only then will we see that change. Until then we will continue to see a lot of talk but no action.”

To see the digital version of this review, please click here.

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this review, please email gloria.balbastro@tr.com.