A difficult 2016, dominated by the failed coup and the government’s heavy-handed response, ended on a high note for Turkey, with growth picking up for the final quarter and remaining relatively strong throughout 2017. But few expect the momentum to last, with the country facing considerable economic challenges and serious doubts about the government’s willingness or ability to tackle them.

The attempted coup in July 2016 cast a long shadow over Turkey’s economy, weighing on foreign investment and the currency and deterring tourists, thereby undermining growth. And while sentiment picked up towards the end of the year, Turkey’s constitutional referendum in April provided fresh uncertainty, removing democratic checks and balances and increasing the risk of sudden policy changes.

Markets were in no mood to dwell on such concerns, however, appearing content to have the constitutional matter settled. The recovery that began late last year has so far proved enduring, with Moody’s revising up its earlier growth forecast to 3.7% from 2.6%.

Reduced political tensions created a better environment for business while also encouraging a pick-up in tourism, especially from Russia and Israel. Government stimulus measures, such as tax cuts and a credit guarantee scheme, also contributed to an improved economic outlook, along with increased currency stability – following a sharp fall last year – and rising exports.

These more transient factors supported some of Turkey’s more fundamental advantages. It enjoys favourable demographics, a diverse economy and relatively low government debt, though the level of that debt denominated in foreign currencies rose to 40% at the end of January, up from 35% in 2015. Its debt is also increasingly long-dated and at a fixed rate, providing protection when global interest rates start to rise.

Despite these advantages, the fear is that Turkey’s recent strong performance is more dead cat bounce than sustainable recovery. Despite improved circumstances, Standard & Poor’s expects growth to come in at 3%, well below the 6% average growth recorded between 2013 and 2016, with the reduction in political tensions not enough to offset the negative implications of currency depreciation on consumption. The lira lost 21% of its value against the US dollar and 17% against the euro in 2016 as the trade deficit widened.

“[The Turkish lira] remains one of the weakest performing major EM currencies this year despite an accommodative global bond and European growth environment, a conservative CBT and rising real deposit rates, and a strong rebound in portfolio inflows,” said Gyorgy Kovacs, economist at UBS.

Of course, a weaker currency has its advantages as well as its disadvantages, and “Turkey’s flexible exchange rate regime will enable the economy to adjust to external shocks”, said Trevor Cullinan, credit analyst at S&P. However, the economy’s “high dollarisation, especially in the corporate sector, limits the benefits of a weaker Turkish lira to the economy as a whole”.

William Jackson, senior emerging markets economist at Capital Economics, is even more pessimistic on growth than S&P, arguing the bump in Turkish growth following the collapse in activity after the coup has flattered its numbers this year. “Growth will be weaker than most expect in 2018 and 2019,” at 2.5% and 2.8%, respectively, if not lower, he said.

The government stimulus packages that have played an important role in supporting Turkish assets are set to be withdrawn, with the credit guarantee scheme running out of funds and tax cuts set to expire by the end of the year. That will likely drag on growth going into 2018, said Moody’s. Meanwhile, accommodative fiscal policy and slower growth have taken their toll on public finances, reducing the chances of further government support.

Even the relief provided by increased political stability could give way to growing concern about the negative impact of President Erdogan’s consolidation of power. With decision-making increasingly centralised, there is greater scope for political unpredictability, with policy influenced by personal whims. Confidence in the rule of law and property rights is fading.

Meanwhile, doubts about central bank independence that have persisted for years will only grow, with interest rates having been held low for political expediency, despite inflation – at 9.6% in July – being well above the 5% target.

Erdogan’s tightening grip on Turkish policy “could delay the implementation of further structural reforms – including labour, educational, severance pay, and energy reforms – to wean the economy off its dependence on foreign financing”, said Cullinan. Such delays could lead to a reversal of capital inflows, he added. And if the unemployment and growth pictures do not improve that could lead to even further delays for much needed structural reforms.

But, for Jackson, the biggest risks of all lie in the banking sector. “Over the past decade, the expansion of private sector credit in Turkey has been larger than in any other major emerging market, with the exception of China,” he said. Such credit booms usually indicate a deterioration in lending standards, meaning at some point there is likely to be a rise in non-performing loans, which could weigh heavily on growth.

Combined with the country’s low savings rate, this spells trouble, said Jackson. “Given the vulnerabilities that have built up in the banking sector, the risk is that the slowdown could be sharper than even we anticipate.”

Receptive markets

While investors have been mindful of such concerns, they appear relatively trivial following the dramatic events of last summer and have not prevented the sovereign from making successful forays into the markets.

The month after the constitutional referendum, Turkey sold a US$1.75bn 30-year bond at a yield of 5.875%, its fourth international bond in 2017 – but its first 30-year in more than three years. That deal meant Turkey had secured its annual external financing needs with only half of the year gone, with total borrowing of US$6.25bn, including a US$1.25bn six-year sukuk transaction.

It was not all plain sailing. In June, it surprised the market by missing its pricing target on a relatively rare euro-denominated bond, pricing at the wide end of final guidance at a time when most comparable credits were getting deals done easily. Turkey sold a €1bn 3.25% June 2025 note at 285bp over mid-swaps – 5bp wider than it hoped for, despite the order book closing in excess of €2.5bn. However, banks on the deal insisted they considered it a success.

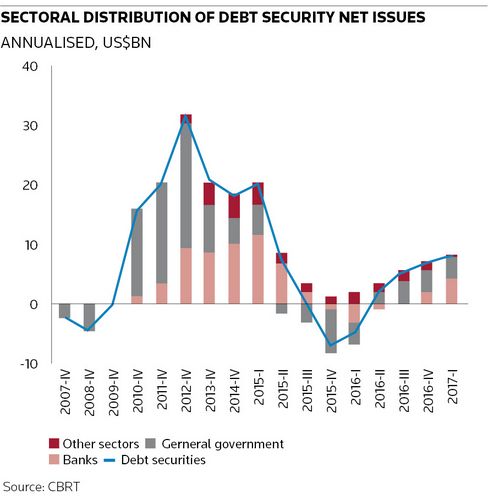

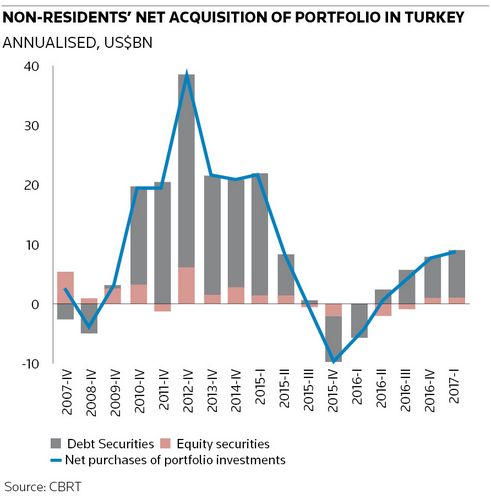

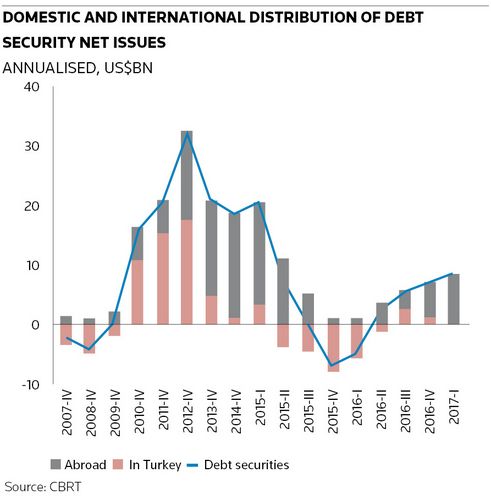

The government also has the safety net provided by a vibrant government domestic debt securities (GDDS) market which has drawn in foreign investors. “Foreigners’ GDDS portfolios have become an important item within the financial account in the balance of payments,” said the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey in its 2017 Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Report.

Non-residents hold 19% of the total GDDS stock, said the central bank, or US$26.3bn as of Q1 this year – a figure that has held relatively steady in recent years, since falling from a high of 29% in 2013. Foreign investment in GDDS has also skewed towards longer dated paper since the sovereign became an investment-grade credit in 2012, with 83% of foreign holdings of GDDS having a tenor of two years or more in Q1.

The generally positive response to the sovereign set the tone for Turkish financial institutions too, with a number of banks coming to the international market in the months following the referendum. In May, Garanti issued US$750m 10NC5s with a yield of 6.125%, while June saw Isbank issue US$500m 11NC6s at 7%. In July, Odeabank, a bank established in 2012, priced a debut US$300m 10NC5 Tier 2 bond at a yield of 7.625, tight to guidance.

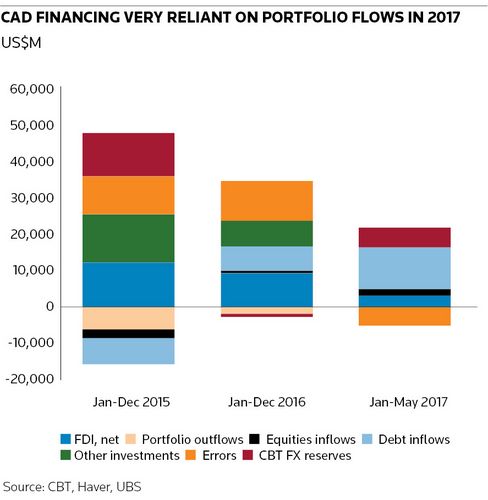

Such deals are crucial for Turkey, especially given its high portfolio flow dependence to finance its current account deficit. Foreign participation is particularly important for such financing given its own institutional weakness. “In January to May almost 70% of Turkey’s external financing came through debt portfolio inflows, both sovereign and corporate. Including equities, the share approaches 80%,” said Kovacs.

Cullinan said: “Turkey’s external position remains its key structural weakness, owing to the substantial net external liability position and related high external financing needs.” S&P estimates Turkey must roll over about 40% of its total external debt in 2017 – around US$165bn, or 21% of its GDP. This leaves it vulnerable to a deterioration of market conditions, which would result in financial sector stress, increased governmental contingent liabilities and a sharp economic slowdown, he said.

For a government that habitually behaves in a way that is likely to scare investors, that must be a concern.

“To the extent that domestic tensions also raise questions about property rights, foreign direct investment’s role in financing Turkey’s large current account deficit is likely to remain well below the highs of the ruling AKP party’s first term in office,” said Cullinan. In 2006, it amounted to 3.5% of GDP.

To see the digital version of this report, please click here.

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email gloria.balbastro@tr.com