Back in 1992, IFR’s Duncan Balsbaugh got a ringside seat from his position on Morgan Stanley’s London trading desk to watch George Soros’s attack on sterling. They say you can’t fight central banks, but as Soros showed, you can – and you should!

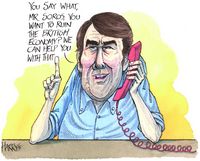

London, September 1992: That dreaded phone call from your boss – can you come to my office, on the hop?

Bloody hell, what whingeing salesman had I beat up this time, or could it be a midday risk exposure check or, worse, yet another meeting with the lawyers.

But it was none of those things: instead, at that meeting and several more over the following days I was recruited to help plot an assault on an elderly woman – the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street, aka the Bank of England.

I was running Morgan Stanley’s fixed-income balance sheet in Europe and that meant that when George Soros’s US$7bn Quantum fund wanted to leverage its bets against sterling, I was the go-to guy.

Stanley Druckenmiller, the chief architect of the Soros attack on the pound, needed to warehouse huge size to leverage Quantum’s holdings of European government bonds in order to have as much cash available as possible as it went into battle. And he chose Morgan Stanley (which under Bob Diamond as European head of fixed-income had risen to become the premier bond trading shop in Europe) to do it for him.

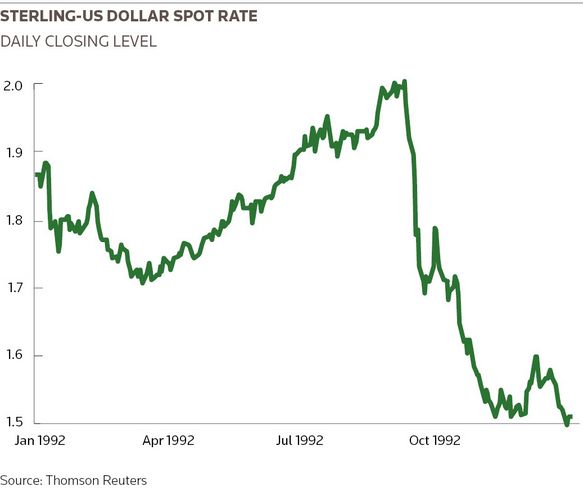

All that cash would soon be employed by Druckenmiller to borrow sterling in the forward foreign exchange market, which was then dumped in the spot market – and in the final hours to the only bid, the Old Lady herself.

Druckenmiller had started betting against the pound in August as it became crystal clear to the prescient positioner that the pound was locked into the European Exchange Rate Mechanism at a range versus the Deutsche mark that was far too lofty. (For younger readers, the ERM was a system designed to stop European exchange rates fluctuating too widely as a precursor to the introduction of the euro.)

The Bundesbank had just raised rates to a record 9.75% as it fought surging inflation. The newly elected British Prime Minister, John Major, did not want to further aggravate slowing growth amid a recession and thus refused to match the rate rise.

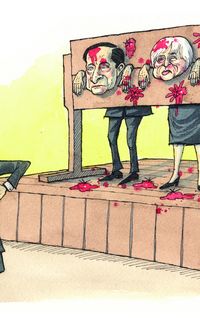

Instead, Major had his Chancellor of the Exchequer, Norman Lamont, practically on his knees begging the Bundesbank’s Helmut Schlesinger for a rate cut at the September 4 finance minister meeting in Bath.

But Schlesinger dashed from Bath loudly and brashly instructing Lamont to raise rates or leave the ERM.

It is important to note that it was Major, Lamont and (less so) Major’s inner circle that were making monetary policy decisions for the UK. The Bank of England did not become independent from government until 1998, and UK market practices were still not up to date in the early 1990s, with not even a Gilt repo market.

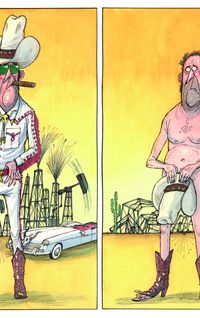

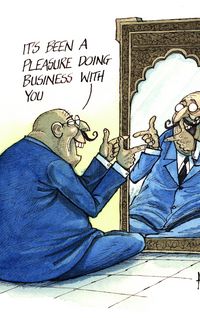

That Major and Lamont were playing billion-dollar-a-hand poker with major gun-slingers like Soros and Druckenmiller proved to be an understatement

The combination of antiquated markets and financially inept politicians running monetary policy proved to be a toxic shock for the Old Lady and her UK citizens.

That Major and Lamont were playing billion-dollar-a-hand poker with major gun-slingers like Soros and Druckenmiller proved to be an understatement. Their stunning lack of market understanding was akin to bringing the proverbial knife to a gunfight. Thus it would be bloody but over in hours once battle was joined.

Ramped up

Global market volatility ramped up to new levels on September 7 when the Bundesbank dropped interest rates a measly 25bp, and Italy simultaneously devalued the lira by 7%.

To make matters worse for the hapless Major and Lamont, talk soon boomed that the rate cut was a German government-led initiative that the Bundesbank did not fully support.

And with the lira devalued, speculators set their sights on the weakening pound with the finale only about a week away.

By now Druckenmiller was increasing outright short bets on sterling, selling short-sterling futures and buying German bonds that mimicked short pound versus long Deutsche mark main positions and to a lesser extent short pound versus French francs plus long US dollar/Treasuries.

My desk watched Soros like hawks while making any balance sheet repo accommodations for Quantum and hedging our books for higher rates. With post-trade tips from our futures desk we shadowed Soros shorting short-sterling futures, loading up shorts despite no real short-end exposure to the very illiquid (and repo-less) Gilt market.

It was Tuesday September 15 – the day before what became known as Black Wednesday – that actually sealed the pound’s fate. Schlesinger gave an interview, which he would later regret, to Handelsblatt and the Wall Street Journal with the customary procedure that his quotes would be rubber-stamped by the Bundesbank. However, the reporter at Handelsblatt ran an abbreviated version that evening – without quotes – knowing that all Schlesinger’s words were on tape.

The story said that Schlesinger wanted a much larger ERM realignment (than had occurred in the recent lira deval), with an obvious implication for sterling.

Bazooka!

What did Druckenmiller bring to the fight against the Major/Norman knives? He had wanted a rifle but his boss Soros dictated a bazooka. Indeed, Druckenmiller right after reading the headlines from the Schlesinger interview told Soros he was going to sell US$5.5bn worth of pounds. Druckenmiller says Soros “winced”, making Druckenmiller think that Soros was going to stop the entire trade, only to hear him say “go to 200%” – meaning, bet as much as US$14bn versus the pound.

What did Druckenmiller bring to the fight against the Major/Norman knives? He had wanted a rifle but his boss Soros dictated a bazooka

The next day – Black Wednesday itself – it became apparent that the Old Lady was about to be stampeded at the ERM floor for the pound.

The government early in the morning began to use its reserves – US$1bn to begin with, then as much as US$5bn – but Druckenmiller knew he could swallow those sums whole. And he wasn’t on his own: there was a cavalry behind (and often frontrunning) Quantum’s pound sales – hedge funds such as Tudor, Bacon and Kovner, not to mention a leveraged legion of banks, were all pounding the pound.

Whipsaw

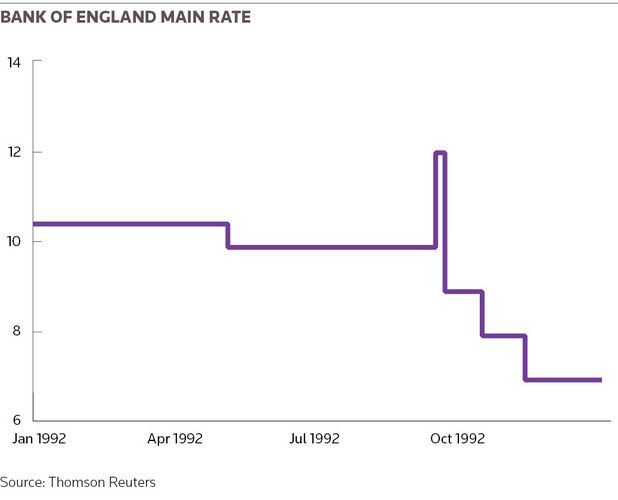

While burning through more than US$2bn-worth of pounds per hour, the bumbling Brits raised rates by 200bp to 12%. But our trading desk noticed a whipsaw snap-back soon after sharp selling in short-sterling futures. I confirmed with our futures desk that it looked to be Soros buying and we noticed he had been adding positions in German, French and even Italian bonds throughout the day. We covered shorts and followed up with longs, shadowing Soros.

It dawned on me then that the end-game of breaking the pound would lead to lower rates and it was entirely likely that Druckenmiller’s plan was always to try to kill the currency but, regardless of that outcome, end up long short-sterling, Gilts, and a bunch of other European government bonds. We greedily added to short-sterling longs but then were stopped out of chunks from resting stops as Lamont announced a rate rise to 15%.

Lamont was no longer on board with defending the pound at any cost – not wanting this additional rate rise poison with the UK economy still in recession – but Major seemed set on going down with the ship.

The pound barely bounced on the 15% announcement and short-sterling was zooming again. Thus we grabbed chunks at the market, rebuilding bets for rates to come down. Getting over-position limit longs was not a difficult task, even amid the turmoil, since our bosses were fixed at our desks.

We were only a scant few hours from a Soros victory. Lamont soon waved the white flag and retracted the move to 15%. The pound and interest rates plummeted. It was over – and Soros, Druckenmiller and the Quantum fund, had won.

So, too, had we at Morgan Stanley.

While we couldn’t match the over US$1bn Quantum had reputedly made, Morgan Stanley had made many millions mainly in rates and foreign exchange trading by identifying and shadowing Soros’s moves.

The lessons?

But beyond the enjoyable telling of old war stories, there’s a lesson in all this: and that is that the markets, like Mother Nature, always win.

Central banks, even when banded together, are no match for the markets, especially when the central banks are (as in the ERM) trying to plug the dyke of diverging fundamentals.

Of course, the major global central banks are again banded together, this time manipulating supply and demand to keep rates near zero (or in many cases in Europe even negative).

So is it time to fight the Fed (and the other major central banks) like Soros did with the Bank of England?

I think so.

There is empirical evidence that quantitative easing and the resulting increase in central bank balance sheets sees non-linear diminishing positive returns, and those positive returns have really only been in the equity markets not the economy.

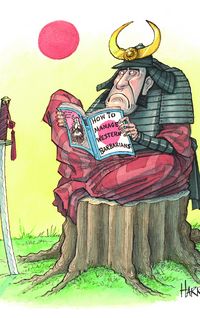

Those diminishing positive returns are best illustrated in Japan. The Bank of Japan’s balance-sheet is approaching 75% of GDP with a leverage ratio many times that of Lehman Brothers when it collapsed.

With the BoJ now buying all or more of Japan’s sovereign issuance, it has turned to buying stock and real estate ETFs, and now the BoJ owns almost 55% of all Japan stock ETFs.

Simply put, unborn Japanese children will be born into a weaker yen, more debt (total debt now 670% of GDP), for a policy that simply increases the living one-percenter’s wealth via higher stocks.

Will central banks ever sell the near-US$16trn of assets they (the BoJ, the US Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and the People’s Bank of China) have mainly bought since 2008 (it was closer to US$5trn before the financial crisis), even assuming we believe the PBoC numbers? By buying ETFs, Japan is loading up on assets that do not mature – do they even have an intention to sell them?

Will negative rates cause massive instability through currency disintermediation (physical cash cheaper than negative yields)? Certainly, negative yields have led to flash crash sell-offs in the bund market with neck-snapping price convexity.

The only way for a leveraged entity to make money in a negative rate environment is for those negative rates to get more negative. As for buy-and-hold investors, they face a virtually guaranteed principal loss.

Time for a fight

I say the time has arrived to fight the central banks: they are all lined up with the same positions attempting to defy supply and demand and having put the global markets all in the same position – reaching for risk to make historical returns since there is no longer a risk-free rate of return (rather, what’s on offer is return-free, but filled with risk).

The grand experiment has seen central bank’s extraordinary monetary policies become fiscal policies, paralysing politics by allowing a debt explosion from countries and companies that is pulling demand forward today, and will thus not be there tomorrow.

Watch the 30-year bond in the coming months: if confidence is ever lost in the global central bank put, flagpole steepening will be the market salute.

I can envision panicking markets where bonds (particularly credit) and stocks collapse simultaneously with no central bank able to stem the tsunami.

Guess who recently said this: “All you do when you’re doing this [introducing QE and/or zero and negative rates] is you’re pulling demand forward to today. This is not some permanent boost you get. You’re borrowing from the future. I think there’s been such a misallocation of resources that this has gone on so long and unnecessarily, the chickens will come home to roost.”

Yes, it was Druckenmiller, speaking in November 2015. And as he showed in those frantic weeks in 1992 – and has shown in the decades since – he knows what he’s talking about.

To see the digital version of the IFR Review of the Year, please click here .

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email gloria.balbastro@tr.com .