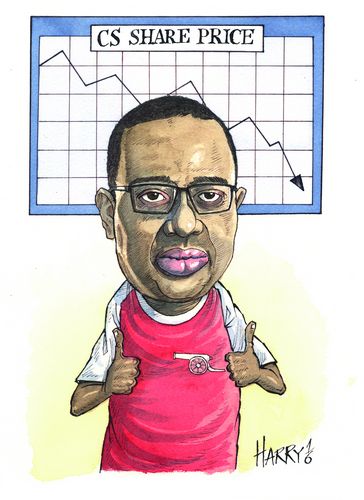

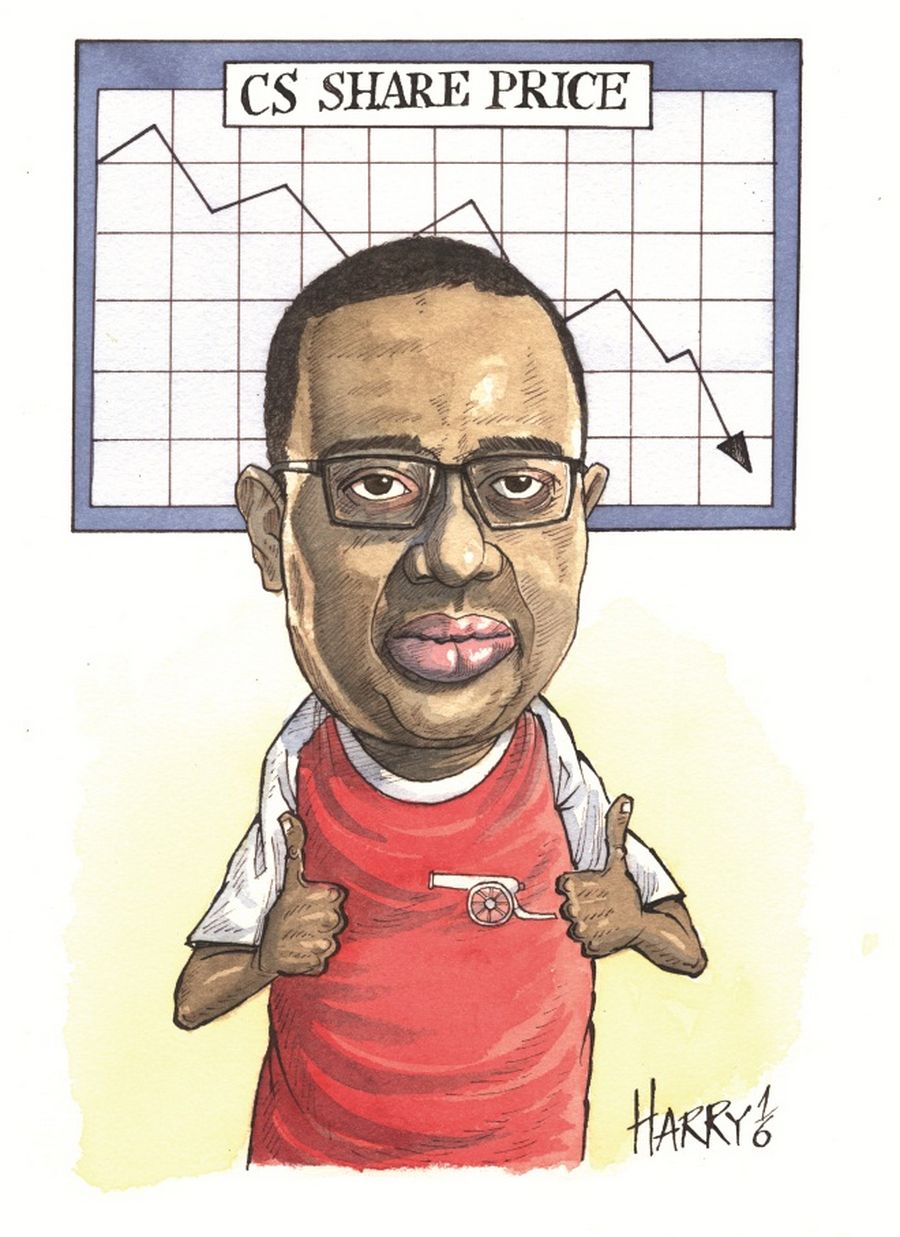

TIDJANE THIAM HAS been told he doesn’t know what he’s talking about by Arsene Wenger, coach of his beloved Arsenal Football Club.

That could explain why criticism lobbed at Thiam in a troubled first year in charge of Credit Suisse has failed to dent his renowned confidence.

Thiam is not a fan of Wenger, and he told the Gunners’ boss as much a few years back. Wenger needed to fix a leaky defence, Thiam believed. In fact, he admits he “launched into a diatribe” about the issue when they sat together on a panel about business and football.

“He said I didn’t know anything about football,” Thiam later recalled of Wenger’s response.

Thiam, undeterred, has continued to support Arsenal and watches when he can. In fact, the chatter within Credit Suisse is that he continued to send Wenger his analysis even after the putdown.

That would be in character for strong-minded Thiam. He has remained bullish despite seeing Credit Suisse shares halve since taking over.

Thiam’s first anniversary in charge of Switzerland’s second biggest bank was July 1 and last week he reported second-quarter results showing his turnaround plan is gaining some tentative traction (see “Credit Suisse cuts 1,000 London jobs as turnaround gains traction”).

His critics say Thiam lacks banking know-how. He was blind-sided by US$1bn of trading losses and he restructured the investment bank five months after an initial plan didn’t go far enough but gave a muddled message on the plans.

Much of that reflected the difficulty of restructuring at a time of industry turmoil, Thiam said.

“I happened to have taken my job at a time just before banks turned into a huge storm,” he told reporters last week.

But he said he had no regrets. “I chose it in full awareness of the challenges. It’s fascinating and I’m actually quite enjoying it.”

PEOPLE WHO KNOW Thiam describe him as intelligent, sharp and often charming. Smartly dressed, the multi-linguist (who lists “The Brothers Karamazov” by 19th century Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoyevsky as his favourite book) enjoys an active social circuit in London and Davos, where he was co-chair of the World Economic Forum this year.

Thiam, who turned 54 on Friday, grew up in Cote d’Ivoire, the West African country of 23 million people with strong French ties that produces a third of the world’s cocoa beans.

His mother had a privileged upbringing and was the niece of the Ivorian president; his father grew up in a small village in Senegal and made inroads as a politician in Cote d’Ivoire before being imprisoned for three years when Tidjane was a baby, due to what the son later described as fabricated charges of plotting to overthrow the president.

Thiam said that has helped him keep things in perspective.

“If you’ve been in a situation where you have nothing, there’s nothing much you are afraid of,” he said on a BBC radio show in 2012, which provided rare insight into his character and background.

Thiam joined McKinsey in Paris after studying at French business school Insead. He returned home to become an Ivorian minister and stayed there after a military coup in 1999. He turned down an offer to become prime minister – later recalling he didn’t agree with any violence mixing with politics.

After a spell back at McKinsey, Thiam was lured to Britain by insurer Aviva and after six years there jumped to Prudential, where in 2009 he became the first black CEO of a FTSE 100 company. In five years as the leading “Man from the Pru”, the insurer’s shares trebled and Credit Suisse swooped for him.

But since arriving with a big reputation, investors have grown restless and there is mounting internal disquiet at some mis-steps he’d taken.

In April, Thiam suggested traders had hidden losses from him and senior executives, before correcting himself to say no position limits were breached. And after last year saying he was happy allocating capital on the “ugly ducklings” of credit and securitised products because they generated returns of 35%–40%, he did a U-turn and unveiled big cuts there.

“Thiam has locked himself into a strategy where he’s destroying his future revenues,” said one banker who recently left, saying the mood within the investment bank was depressed.

Thiam’s supporters say he inherited a bank in worse shape than outsiders knew and he will inevitably tread on toes as he cuts the importance of the investment bank and puts more focus back on the wealth business, especially in Asia. The supporters say people are happier in other parts of the group.

But Thiam has admitted in the past he is not always comfortable leading people.

“It’s a bit like walking a tightrope because you feel all these expectations around you and it’s rarely comfortable,” he said. “But if you really believe in what it is you are trying to achieve it helps you go through a journey and walk without looking down. Once you start looking down, you risk falling.”

Tidjane Thiam