The pressure on Greece has subsided since the height of the crisis, with no unmanageable repayments due imminently. But the country has barely scratched the surface of the painful reforms needed to deliver dynamic growth and many still feel debt forgiveness is the only realistic route out of its malaise.

Greece’s creditors remain divided. The EU remains committed to ensuring Greece achieves its primary budget surplus of 3.5%, the fulfilment of which has forced the country to make deep cuts in spending. Yet the IMF believes the figure is unrealistic and has argued for some debt to be forgiven, allowing it to ease cuts and shift the focus onto productivity-boosting structural reforms. For the Eurogroup, debt forgiveness is politically problematic.

In June, the two sides found a temporary compromise, with a proportion of European Financial Stability Facility and European Stability Mechanism loans re-profiled. The Eurogroup has promised to extend loans from the EFSF, while providing deferrals on debt service at the conclusion of the ESM programme in August 2018.

This will give Greece more time to find the money to repay its creditors. It does not have any large redemption payments to make until the €2bn due in May 2018, with bigger payments not required until 2024 and then 2033.

Aarti Sakhuja, credit analyst at S&P, said: “The amortisation of Greek debt will peak in 2019 at about €13.5bn, an estimated 7% of GDP; however, we expect the government to issue market debt to smooth upcoming redemptions, including the 2019 maturities. In every other year from 2018 until 2023, we estimate that repayment obligations will be less than 4% of GDP.”

But disagreements about debt forgiveness remain. The current IMF programme ends in August 2018, so all parties must agree a package they can live with by then to ensure the IMF remains engaged with the process. Few expect any significant progress in negotiations until after the September German elections, and potentially the spring Italian elections as well.

Yvan Mamalet, senior euro economist at Societe Generale, agrees with the IMF. “If Greece doesn’t see debt relief large enough to bring its debt-to-GDP levels down to more manageable levels, we could potentially see the Grexit option back on the table,” he said.

But given the IMF’s stake in the process is only €2bn, compared to the €86bn provided by the ESM, there is no guarantee this argument will prevail.

The case for debt forgiveness may be harder to make as Greece is enjoying a period of relative stability, with its stock market relatively strong and foreign investment picking up. FDI should continue to come in, given only around 19% of the promised €15.2bn of EU structural funds for the 2014-2020 programming period has been disbursed, said Moodys. The European Investment Bank and European Bank for Reconstruction and Development are also set to invest.

The Greek €3bn five-year sovereign bond yielding 4.625%, issued in July, supports the narrative of normalisation in Greece. Its first deal in three years was expensive, but not excessively so in the circumstances, suggesting the market is now open to the sovereign. There is talk of Greece issuing another bond before the end of the year, followed by up to two more next year.

Yet the deal was not a game-changer for Greece, said Mamalet. “Greece’s recent sovereign issue was probably at least as much about politics as its financial position. It was issued at a similar interest rate to its last bond, which allowed the government to show the country was returning to normality. In reality, this was merely rolling over existing debt.”

Others worry the bond sale was a mistake that will relieve the pressure that has incentivised the progress Greece has made to date. Spending pressures will increase once elections draw near, and market access may tempt the government to borrow more to finance vote-winning measures.

Bankers will argue that the deal helps other Greek borrowers, emboldening them to follow the sovereign back into the market. The four largest Greek banks sold a combined €2.25bn of senior unsecured debt around the time of Greece’s €3bn 4.75% five-year in April 2014 and there is evidence something similar could happen again: Eurobank and National Bank of Greece were among those eying the market this year following the sovereign deal.

But Dimitris Paraskevas, managing partner at Elias Paraskevas Attorneys in Athens, said such borrowers had access to capital even before the Greek bond.

“The top 50 or so Greek companies could already access the market even before the sovereign deal. They have a good relationship with Greek banks and even had access to international markets,” he said.

The problems are more acute for the majority of Greek companies, many of which are small, family-run businesses, below that top tier.

A long way to go

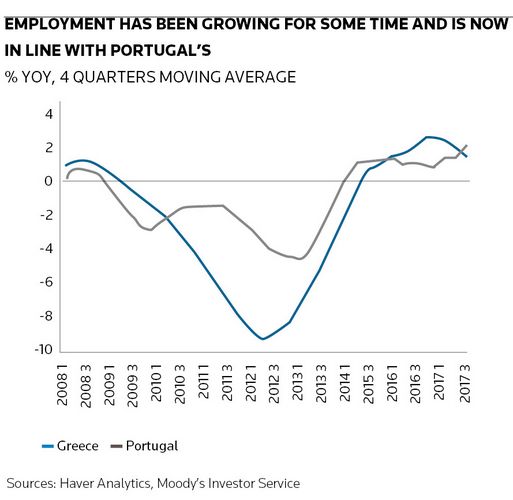

Greece has made a lot of progress on the structural reforms the IMF hopes can lift growth but, having started from a lower base than other EU countries, it is still not up to the OECD standard. Progress has clustered in certain areas, such as labour market reform, but in other areas has been lacking. A bold plan to raise €50bn, or about 30% of GDP, via privatisations amounted to little.

The incentive to push through politically unpopular structural reforms is undermined by the difficulty projecting how and when they will pay off with improved growth. In Germany, it took five years for its efforts to pay off in GDP growth, while Spain appears to be reaping the benefits of reforms it implemented three years ago already. Greece has been working on these reforms for around eight years so far but is nowhere near the level at which growth makes its debts look affordable.

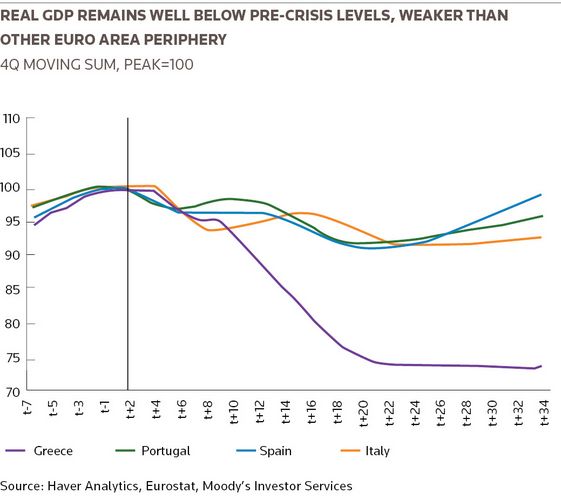

Moody’s analysts said: “The current forecasts of the IMF and the European Commission assume real GDP growth of 1%–1.25% per annum over the medium to long term, which is low even in a European context and even more so against the substantial output losses that Greece experienced. At this rate, it would take Greece until the 2040s to reach its pre-crisis level of real GDP again.”

However, despite the obvious challenges, the ratings agencies can all be described as cautiously optimistic – at least compared to the picture in the recent past. In August, Fitch upgraded the sovereign, while S&P has revised its outlook to positive from stable while affirming its B– rating for long-term foreign and local currency sovereign credit.

S&P projects that over 2017–2020 Greece will report general government primary surpluses of about 3% of GDP annually on average, alongside average nominal GDP growth of 2.8%. That should allow general government debt to decline to 158% of GDP in 2020, from 179% in 2016.

“Over the next 12 months, there is at least a one-in-three probability that we could raise the ratings,” said Sakhuja.

For the Greek population itself, the outlook is bleaker, with pensioners particularly badly hit by cuts. People have stopped spending on luxuries: meat consumption is down, while newspaper and magazine circulation has fallen by 30%, according to one estimate. Despite the shrinking of the economy, the cost of living remains relatively high compared to neighbouring countries.

The low savings rate leaves Greece exposed to external shocks despite being a relatively closed economy driven more by domestic consumption than foreign trade. An exodus of deposits has left its banking system looking weak. Non-performing exposures still constitute nearly half of system-wide loans, according to S&P, despite attempts to tackle the problem, such as legislation to facilitate out-of-court restructuring, the development of a secondary market and electronic auctions.

There are some more positive signs. “Real estate prices look like they have bottomed out; I don’t think we will see prices fall much further from here,” said Paraskevas. “The problem is they don’t look like rebounding higher either, unless you have a property that is attractive to foreigners.”

Tourism has picked up too, but that has done little for the overall economy, as many visitors come on package deals and do not spend locally. Where people do spend with Greek businesses, rampant tax evasion means little of it finds its way back to government coffers.

The government has made some progress improving its tax collection, but it remains one of the country’s biggest challenges. It has invested in better software that can cross-check records to track what it is owed. Improved enforcement means tax officers now chase even relatively small amounts of unpaid tax, even on the islands. But it still does not collect close to what it is owed.

Greek people are charged income tax, social security contributions, prepayment of tax, tax on dividends, professional duty, real estate tax, a social cohesion tax designed to redistribute wealth for the benefit of society, and non-deductible expenses. While higher taxes look like a good way to raise the cash needed to repay creditors, it is also creating perverse incentives.

The lack of M&A is one example. Paraskevas said: “Scale brings efficiency, which should encourage consolidation, but there are few mergers – in Greece and across Southern Europe generally.

”The main reason for this is that when one is small it is easier to avoid paying tax, and the savings from avoiding tax are bigger than the efficiency gains of merging, a common paradox in the current over-taxation environment.”

The problem is so widespread that the stigma associated with tax avoidance is evaporating. Rather than paying the state for substandard services such as hospitals and schools, many prefer to avoid tax and pay for services privately.

S&P’s Sakhuja said: “Most of Greece’s tax burden falls upon a subsection of the private sector under pressure from difficult credit conditions, an unpredictable business environment and a challenging macroeconomic setting.”

This is encouraging some of the youngest and brightest to consider leaving Greece, though Paraskevas argues the majority that will leave already have. With opportunities in Europe limited and the UK and US looking less welcoming to immigrants, the grass may not look sufficiently greener elsewhere.

To see the digital version of this report, please click here.

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email gloria.balbastro@tr.com