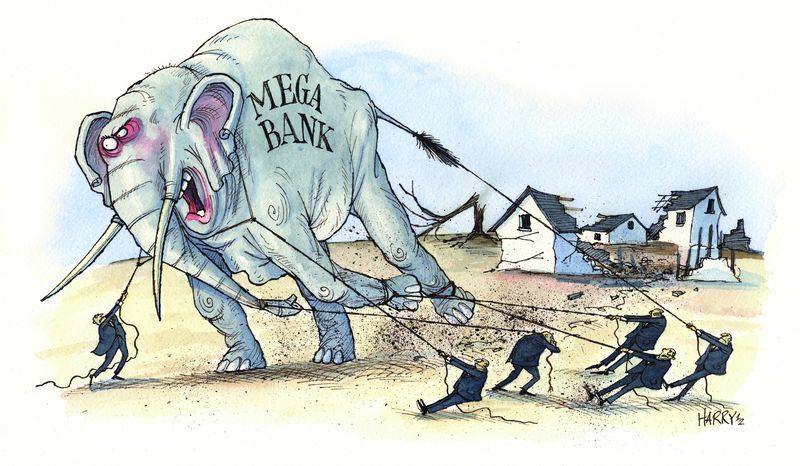

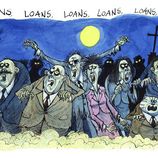

New capital and liquidity requirements under Basel III are likely to have all kinds of consequences – including a slowdown in lending across the spectrum. Banks must find new ways of drumming up capital and cleaning up their balance sheets.

To see the full digital edition of the IFR Review of the Year, please <a href="http://edition.pagesuite-professional.co.uk//launch.aspx?eid=24f9e7f4-9d79-4e69-a475-1a3b43fb8580" onclick="window.open(this.href);return false;" onkeypress="window.open(this.href);return false;">click here</a>.

While the Basel III regulations have yet to be set in stone, many banks believe the new capital and liquidity requirements will stifle all kinds of lending across the spectrum, from interbank loans to commercial paper backstops. Even ECB president Mario Draghi has suggested that the liquidity requirements are “overly conservative”, and banks are trying to loosen some of the proposed regulation.

The industry insists that, under Basel III as currently written, banks will be forced to hold a significant store of liquid assets behind many short-term loans, which amounts to a disincentive to extend credit. Uncommitted credit lines, such as undrawn term loans, working capital facilities and CP backstops, would be particularly affected.

One central reason is the pending imposition of a Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR), under which banks will be required to hold cash (or near-cash equivalents) to cover potential cash outflows over a putative 30-day period of “stress”.

Banks will be required to have at least a 1:1 ratio of liquid assets to those outflows – which include customers tapping into their lines of credit. The LCR regulation assumes that non-financial companies would draw down 10% of their untapped credit lines during a stress period, but that financial institutions would utilise the full 100% of their available credit facilities.

Banks would thus have to squirrel away so much in assets to cover those credit lines, the industry says, that they would simply be deterred from much of that kind of lending. The LCR is scheduled to go into effect on January 1 2015.

The ratio requirement could pose a particular problem in the commercial-paper market, where an underlying revolver is used to backstop a deal. The fear is that, without those backstops, commercial paper will become less desirable.

“The backstops are likely to remain for those companies with deep bank relationships, although costs will go up,” said one banker. “Those that don’t have such deep relationships, or deep wallets, will have difficulty getting availability.”

Meanwhile, bankers expect long-term lending will also feel the squeeze due to Basel III’s liquidity requirements. Banks will have a disincentive to write long-term loans and hold them on their balance sheets, since such debt is an impediment when banks tabulate their risk-weighted assets.

“Loans on asset-backed property, such as aircrafts and project finance, or those that are 15 to 20 years in duration, are rare,” one banker said. “They are heavily penalised in terms of their risk weightings.”

Wholesale changes

Those in the industry say interbank lending, which is facing especially harsh new liquidity requirements, will also be affected at a time when sudden funding droughts have plagued the wholesale market, and even the strongest of banks have been shut out on occasion.

Not wanting to be dependent on funding vehicles that can dry up quickly, banks are understandably looking at alternatives. Executives at BNP Paribas, for example, have been pushing to win more deposits from large companies, as the bank aims to rebalance the way it funds its corporate and investment bank over the coming quarters.

French banks in particular have been battling over what constitutes the high-quality liquid assets that must be set in reserve under the new Basel regulations, and are pushing to expand the range of acceptable collateral.

To date, the Basel committee has decreed that high-quality assets include cash, securities issued by the US government or other highly-rated sovereigns, agency mortgage-backed securities and corporate bonds rated AA or higher.

Analysts say banks are pressing regulators to accept Single A rated corporate bonds as well – a move that critics say will let banks use collateral that would be much more difficult to sell in times of a crisis.

The Basel committee was expected to discuss these standards in its December meeting, with the market clearly keen to know concrete details about one of the most important pieces of the new regulation.

“No one really knows exactly what the LCR requirements will be,” said Jonny Fine, managing director and head of investment-grade syndicate at Goldman Sachs. “It makes it more challenging, having this uncertainty.”

According to a September report by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), banks having more than €3bn in capital had only 91% of the capital needed to comply with the LCR requirement.

“This means that there is a high probability that only six of the 28 global systemically important banks… will be subject to Basel III regulations from the globally agreed start date [of January 1 2013],”

It said that those banks still needed to compile €1.7trn in liquid assets, based on end-2011 figures, to meet the liquidity ratio – and that they were €374.1bn shy of the common equity capital requirement of 7% of risk-weighted assets.

The BCBS said the large banks had an average common equity Tier 1 holding of 7.7%. The top global systemically important financial institutions (G-SIBI) must hold 7%, plus a surcharge of 2.5%. (Other systemically important banks must hold an extra 1% to 2%.)

That said, it seems as if banks will have some time to catch up. According to the Financial Stability Board, only eight of the 27-member jurisdiction have issued a final set of Basel III related regulations, with Japan the only major nation to do so.

“This means that there is a high probability that only six of the 28 global systemically important banks… will be subject to Basel III regulations from the globally agreed start date [of January 1 2013],” wrote FSB chairman Mark Carney.

US regulators have already said that America’s new capital rules would not take effect by then, while finalisation in Europe is expected to take several months more.

Making a move

Not every financial institution is behind the curve, however.

In order to reduce their risk-weighted assets, many banks have sold off a significant number of non-core businesses, while others have reined in long-term lending or exited markets altogether.

In a recent report, Fitch Ratings attributed the success of US banks in building their Tier 1 capital to their ability to reduce risk-weighted assets, especially in the face of earnings headwinds.

Bank of America, which just three years ago looked as though it would have to issue common stock to meet capital requirements, has bounced back to a level where it would likely already be in compliance with Basel III capital requirements.

Meanwhile JP Morgan recently won approval from the Federal Reserve to repurchase up to US$3bn in common stock in the first quarter – about six months after it put repurchases on hold following the “London Whale” trades.

Banks have been trying to adjust risk weightings by selling off loan portfolios or encouraging clients to refinance through the bond market, where funding is inexpensive – and where the banks can earn fees.

With rates hovering near historic lows, corporations have been willing to oblige, whether in commercial paper or long-term bonds.

And as a result, European corporations, which have traditionally relied on the loan market, are starting to tap into the bond market like never before.

European corporates are trying to determine whether it is better to do a DCM deal in Europe or enter into the US dollar market and do a swap. However, the cost of swaps has risen due to regulatory charges.