Jean Pierre Mustier wanted out. The Frenchman had been recruited three years earlier by UniCredit chief executive Federico Ghizzoni to help him drive through an ambitious turnround plan for Italy’s biggest bank. But, by mid-2014 differences had begun to surface between the two men about the direction the firm was headed.

The overhaul, grandly named “Vision 2015”, had already begun to flounder. Targets were not being met, and a slowdown in Italy had exacerbated the bank’s festering bad loan problem. On some measures, UniCredit was in worse shape than when the plan had been launched two years earlier: despite Ghizzoni’s pledge that he would turn round the bank’s fortunes in Italy, its bad loans in the country had actually increased by €10bn.

Vision 2015 was ditched and a new plan put together. But Mustier was not convinced. In August 2014, just a few months into the new strategy, he resigned. “I didn’t want to oppose the then management, and so I said ‘it’s better for me to leave’,” he told IFR.

Two years later, the tables have turned. An impatient board dropped Ghizzoni and re-hired Mustier, tasking the Frenchman with nursing the bank back to health after a decade in intensive care. But its condition remains critical: after €13.2bn of writedowns last quarter, its capital levels are now below the minimum allowed by the ECB.

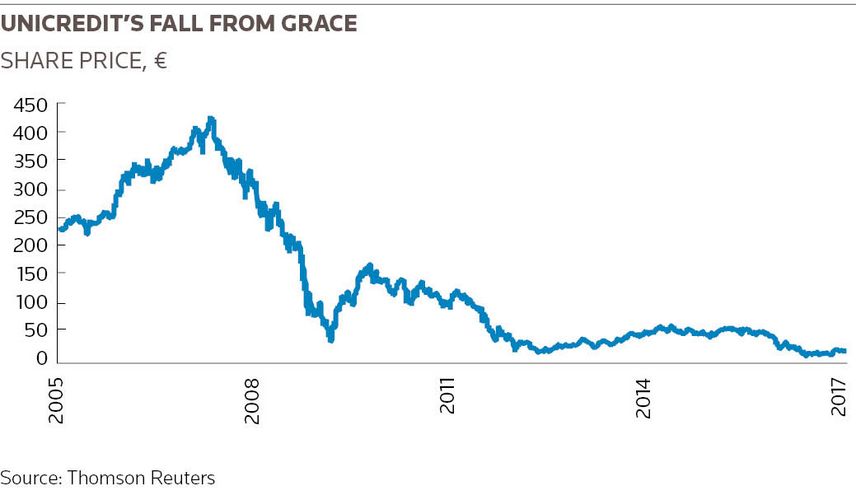

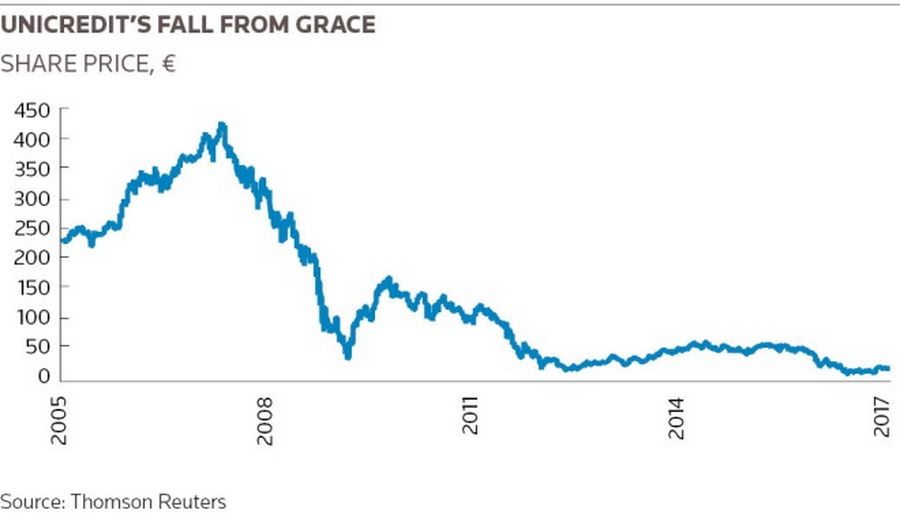

UniCredit’s future now hinges on a €13bn rights issue to replenish capital that is being launched on Monday. Investors are used to being asked for money: since the beginning of the financial crisis, three different UniCredit CEOs have launched four capital raises to fund five overhauls. And the bank has burned through that money: all the €14.5bn raised in the last three capital raises is now gone.

Mustier spent much of January on the road telling investors – both old and new – that this time it was different. Many have bought into that narrative: the shares are up about 10% since the Frenchman announced his latest plan (although they are still 94% down from their 2007 peak), and bankers on the rights issue talk of big changes in UniCredit’s shareholder register since then, with new investors buying in.

Internally, too, there is a feeling that the bank is finally sorting out its issues. “It became increasingly clear that more of a step-change was needed,” said one board member. “The old plan … was too much hype. It wasn’t that management didn’t see the issues; they were aware of the need for change. But previous plans were too cautious and slow.”

BAD LOANS

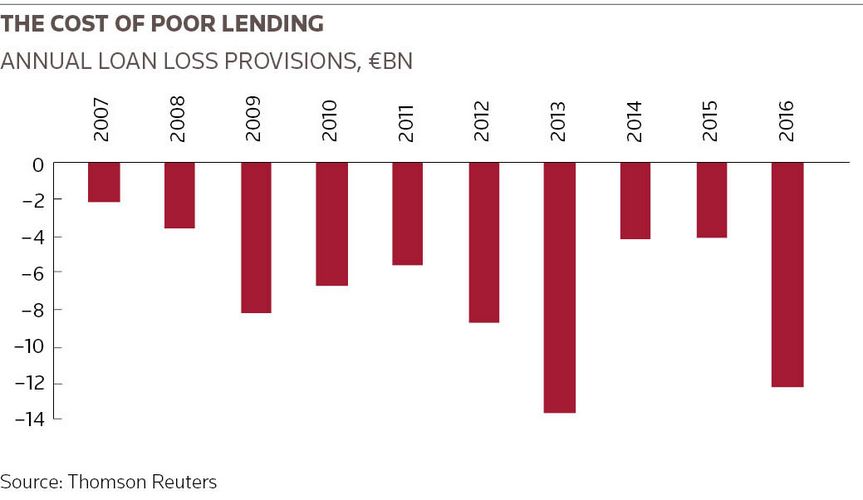

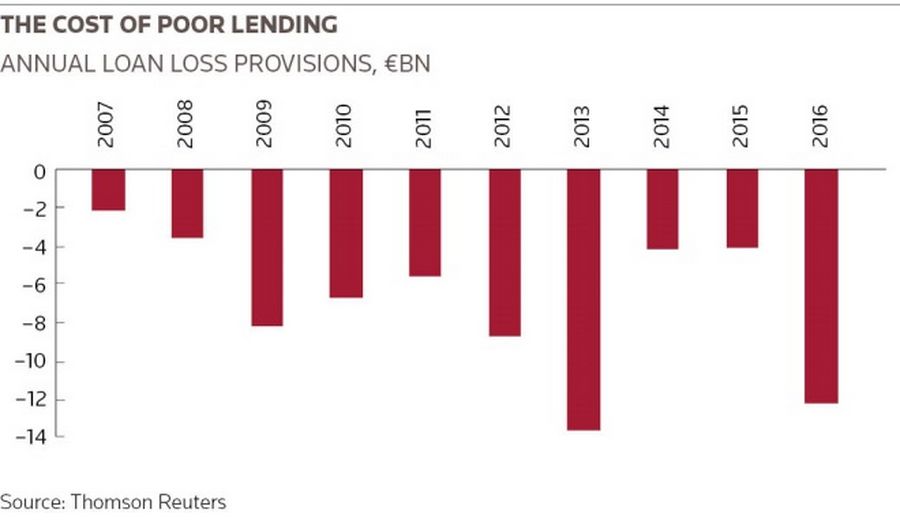

A €77.8bn pile of bad loans is by far Mustier’s biggest problem, with one in every six euros lent out now classified as impaired. No other bank has a bad loan problem of that magnitude. The ill-timed and largely unvetted purchase of Capitalia in 2007, Italy’s economic stagnation and years of poor lending are all to blame.

For years, the problem was dealt with the “Italian way”, according to one senior insider. Loan loss provisions were made – almost €70bn so far – but never enough to actually facilitate sales of the loans to clean up the books. Instead, the responsibility fell on an under-resourced and under-motivated workout area to try to get money from tens of thousands of clients in arrears.

“The old plan … was too much hype. It wasn’t that management didn’t see the issues; they were aware of the need for change. But previous plans were too cautious and slow”

Mustier quickly became convinced of the need to shift as many bad loans as possible off the books. Two days after starting as CEO, he tasked then-markets head TJ Lim with trying to do exactly that. Initially named Project Bastille – it was launched on July 14 – that name was dropped after the Bastille Day attack in Nice that evening.

Lim’s mantra that “failure is not an option” – or FINO – quickly became the new project name. But as he got to work, it became clear that the magnitude of the clean-up would be limited: big chunks of the portfolio such as mortgages and some corporate loans were designated as too sensitive to sell on. Bad “core” loans were also to be left out.

As a result, just €17.7bn of bad loans went into FINO, less than a quarter of UniCredit’s total. The bank met with potential buyers, many of whom had been scarred by previous dealings with Italian banks and doubted whether UniCredit was serious. Difficulties soon arose: data were missing, and buyers were unhappy about servicing and recovery plans.

“We had to prepare during the summer all the loan tape,” said Mustier. “Over 200 people … it was a massive amount of work.” Eventually, a deal was done – just minutes before the bank’s strategy announcement on December 13. PIMCO and Fortress agreed to buy just over half the loans, at an undisclosed price far below the face value of €8.9bn, according to people familiar with the matter.

COSTLY CLEAN-UP

Already in the summer, it was clear the clean-up would be costly. With loans booked well above market prices, facilitating transactions such as FINO would mean billions in writedowns. On top of that were restructuring charges and redundancy money for 14,000 jobs to be cut – as well as the cost of getting capital to the desired core equity Tier 1 ratio of at least 12.5%.

Advisers told UniCredit it needed €20bn. Fortunately for Mustier, Ghizzoni had already mandated banks to sell down two of UniCredit’s equity holdings – in its Polish unit Bank Pekao, and in its online division FinecoBank. The two accelerated bookbuilds allowed Mustier to finish his first week in the job with €1bn already in the bank.

“The ABBs were in the making already, but Jean Pierre was keen to use the sales to signal a change in tone,” said one banker close to the transaction. “That gave him time to work on the bigger plan. Previous management would probably have done the two trades and then called it a day.”

“There were already some plans before Mustier came in. He inherited a lot of ideas,” added another banker who has been advising the bank. “But what he did was make them his ideas, and put some extra pepper into it to make it spicy.”

More difficult was the sale of UniCredit’s asset management unit Pioneer Investments. Ghizzoni had agreed a tie-up with Santander in 2015, but that deal had hit regulatory delays. Mustier pulled the plug and mulled an IPO. Eventually, Amundi Asset Management, which Mustier helped create years earlier, agreed to buy it in December 2016 for €3.5bn.

UniCredit sold another stake in Fineco in October and a 32.8% stake in Pekao in December, bringing down the capital needs to €13bn. But the sales were not without controversy. “Poland was the most difficult decision,” said the board member, who said there were concerns on the board about giving up future growth.

Others have gone much further. “Fineco is one big mistake: it is short term, it’s a business that could be the future of the bank, and they are selling because they are so desperate,” said one person who had advised various UniCredit shareholders. After the sell-downs, the Italian bank still owns 35% of Fineco.

“We used Fineco as the adjustment variable basically to limit the size of the capital increase to €13bn,” admits Mustier, who eyes future growth coming from elsewhere. After the clean-up and capital raise, he is planning to invest in IT, pushing a shift to digital banking and adding resources to do more lending – but more prudently, of course.

CULTURAL SHIFT

The big question is whether Mustier can change the culture of a bank that for years has failed to decisively deal with its problems. “We can applaud what [Mustier and his team] have done, and chances are good that the capital raise will be successful,” said the board member. “But the real question is whether they will deliver. The proof will be in the pudding.”

Several senior managers have already gone, and Mustier has hired an external communications agency to supplement internal operations. New performance measures have been brought in, long-term incentive schemes changed and greater transparency added. IFR spoke to more than a dozen people and all agreed things were changing.

But it will be a major task. UniCredit, even in Italy, is the result of the merger of dozens of small, regional banks, and its expansion through the 2000s was done using several bolt-on acquisitions. Senior managers admit that the group never fully gelled: too many parts of the business were run as mini-fiefdoms, with central management never fully in control.

“Although we have been a group for many years, in reality until recently we were the sum of different parts – a collection of banks,” said Gianni Franco Papa, general manager at UniCredit, who has been with the bank for the past 37 years. “We have always had the potential to offer cross-border products and services but this ability was not fully exploited in the past.”

Politics has also never been far away. Italian charitable foundations were once the bank’s majority owners and although their ownership has been steadily diluted over the years, they have traditionally maintained disproportionate power. “Each region had its say, and the bank was never able to take any strong action,” said the adviser to shareholders.

The capital raise looks set to dilute that power yet again, with many foundations not having enough free cash to fully take up their rights in the capital raise. Board members spoke to IFR of a big shake-up in the make-up of the board in 2018, when the mandate of some members ends and new, more dominant shareholders will demand better representation.

For Papa, the foundations can still add value to the bank: “We like having the [Italian] foundations as our shareholders because this gives us an insight into the local communities in which we operate. In Italy this is very important when you are a large commercial bank,” he said.

With €44.3bn of bad loans still assumed to be on the books at the end of the plan in 2019, UniCredit will also be praying the European economies do not take another stumble. After a decade in intensive care, rehabilitation is likely to take many years still.