High wireless act

In a year of political shocks and whipsawing markets, clients repeatedly turned to one bank in particular for leadership. For stepping up with commitments through all the ups and downs, reopening markets after periods of stress and coming up with creative solutions, Goldman Sachs is IFR’s US Bond House of the Year.

Sprint was already burning through plenty of cash in the autumn as it saw another wall of debt maturities appearing on the horizon, including a US$2bn bond coming due in just a couple months.

The company was keen to cut its reliance on the volatile high-yield market, where it had been the number one issuer of bonds for quite some time. And it needed to reduce its high interest expenses and try to slow its relentless march through its cash stores as it fought off intense competition in the US wireless market.

So Goldman Sachs stepped forward with a unique solution.

It structured a US$3.5bn bond that would effectively mortgage 14% of the company’s wireless spectrum rights, capitalising on Sprint’s most important – and unused – asset.

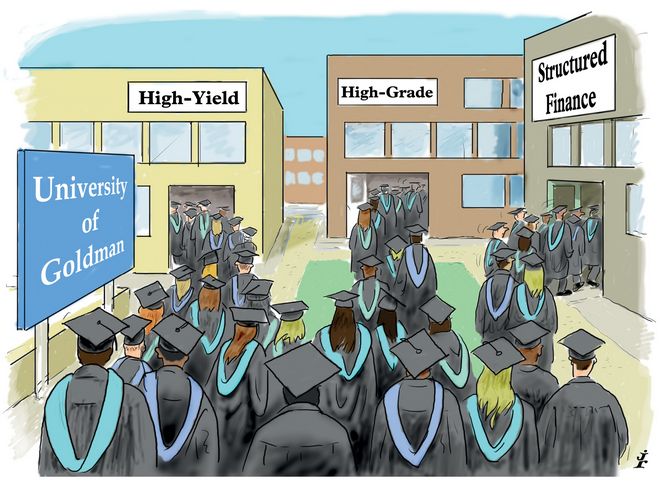

One of the first reactions from rival bankers was to wonder if the deal belonged in the structured finance, high-yield or investment-grade league tables – which underscored just what Goldman was doing differently.

By using spectrum to back the bonds, it was able to secure an investment-grade rating for the Single B rated issuer’s deal, thus opening it up to a new set of investors.

“The Sprint deal is emblematic of what our franchise brings to the table,” said Vivek Bantwal, co-head of the Americas credit finance group in Goldman’s investment banking division. “Our competitors would not have been able to do this … it’s by virtue of how we have organised ourselves,” he said.

His group, created at the start of the year when Goldman merged its leveraged and structured finance businesses, has helped the bank look more broadly at capital market solutions – without infighting about which departments get the profit.

“Sprint is by far one of the deals we’re most proud of across the business,” Bantwal said, “going back a few years.”

A deal of its size would have pushed the envelope in the ABS market alone, but it amassed a US$32bn order book from investment-grade, high-yield and structured-finance accounts.

The final yield on the five-year amortising trade was 3.375% – Sprint’s lowest-ever yield on a bond and less than half the coupon it pays on most of its junk-rated debt.

“When you look at alternatives, the approximate interest saving is in the order of US$100m on a running basis,” said Srujan Linga, a vice-president in Goldman’s investment banking division.

Keeping promises

But Sprint was just one of dozens of clients for whom Goldman delivered throughout the year.

In leveraged finance it signed commitments for deals even at the most uncertain times, such as the days before and after the shock Brexit vote and Donald Trump’s victory in the US presidential race.

Just days after Britain voted to leave the European Union, sending global markets into a tailspin, Goldman signed a debt commitment for private equity firm Onex’s acquisition of a majority stake in WireCo WorldGroup – a lifeline to restructure the business.

It was a bookrunner on seven of the largest LBO deals in 2016, and left lead on four of them. In all, Goldman signed about US$10bn of debt commitments for financial sponsors including Hellman & Friedman’s buyout of healthcare management services provider Multiplan.

Just months later, it brought Multiplan back to market with a dividend recapitalisation deal that was priced just days after the US election amid wild swings in the rates market.

Goldman was the most active bank in the US high-yield bond market in the week before and after the US election on a variety of deals – and its commitment paid off.

By the end of the awards period it was number one in the Thomson Reuters US high-yield bond league table – up from fifth place the year before – knocking US rivals with bigger balance sheets off the top spot.

“We’ve supported clients in some of the most difficult times of the year,” said Kevin Sterling, who heads the bank’s US leveraged finance syndicate desk. “And we didn’t re-cut the terms of what we had proposed. We honoured them.”

The deals were not always easy.

A US$3.9bn cross-border leveraged loan and bond debt package backing Vista Equity Partners’ US$6.5bn buyout of US software giant Solera is probably the best reflection of Goldman’s grit.

The deal was an important test for the market, as it was the biggest LBO since the spectacular collapse of data storage firm Veritas’s US$5.6bn bond and loan package in November – and the market didn’t need another hung deal on its hands.

It came just days after yields on Triple C rated bonds had peaked at more than 20%.

After twists and turns, including some tense phone calls in the early hours, the deal cleared the market at double-digit yields.

It wasn’t in the original shape envisioned – the euro tranche was dropped and the US loan upped in size – but it was credited with bringing LBOs back from the brink.

“At that moment in time, the deal felt twice as big,” said Christina Minnis, co-head of the Americas credit finance group. “Solera reopened the LBO market. It was the litmus test.”

The company also credited Goldman, which wanted to bring the financing to market by the end of 2015 to de-risk its balance sheet.

Solera, however, was reluctant to sell the debt at a discount.

“There were times when they were upset with me,” said Solera CEO Tony Aquila. “But they supported us. After they dealt with the shock of the volatility, we were shoulder-to-shoulder.”

Muscling in

Goldman’s ability to turn up for its clients was not restricted to leveraged finance.

Of note was its role in the US$49.5bn acquisition financing of computer giant Dell’s purchase of EMC.

Goldman was one of six banks to provide bridge financing for the deal, but was brought in after its peers because of concerns that the bank was conflicted on another M&A deal.

Goldman received a call from the borrower on a Friday and signed up two days later for what was a complex transaction including a secured investment-grade bond for a junk-rated issuer – a deal some said could not get done.

“I’ve never seen a bank pull a kind of commitment like that together so quickly,” said a person familiar with the matter.

And there were many other highlights, including some sole commitments for acquisitions that averted any leaks to the media.

These included the US$10.5bn bridge loan for Newell Brands’ acquisition of Jarden and the US$10bn bridge loan for Mylan’s acquisition of Meda, both subsequently taken out in the bond market.

Goldman also helped reopen the market in February with a US$12bn deal for Apple in the wake of an unexpected sell-off at the start of the year.

It was instrumental in the US$1.5bn callable Tier 2 contingent capital bond for Toronto-Dominion Bank – the first time a Canadian issuer had ever sold callable subordinated debt denominated in US dollars.

And as well as remaining a top player in M&A on the sellside this year, it was bookrunner on a number of the year’s biggest M&A bond deals, finishing in the top five in Thomson Reuters’ US investment-grade league table.

“We’ve definitely had a more balanced mix,” said Jonny Fine, head of the Americas investment-grade syndicate desk at Goldman. “About 60% of business done in the last year has been sellside, but we’ve written large cheques and want to be seen as a leading provider of acquisition finance.”

To see the digital version of this review, please click here.

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this review, please email gloria.balbastro@tr.com