Anshu Jain underestimated the bite of new banking regulations installed after the financial crisis, and the misjudgment ended up costing him his job.

When he and Juergen Fitschen took over as co-CEOs of Deutsche Bank in May 2012, Jain – then considered by many as one of the most successful bankers of his generation – assumed that the worst of the post-crisis regulatory onslaught was over.

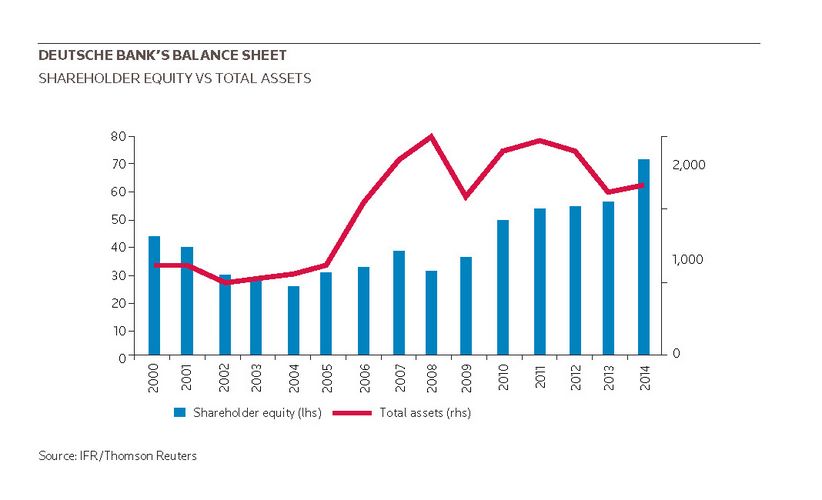

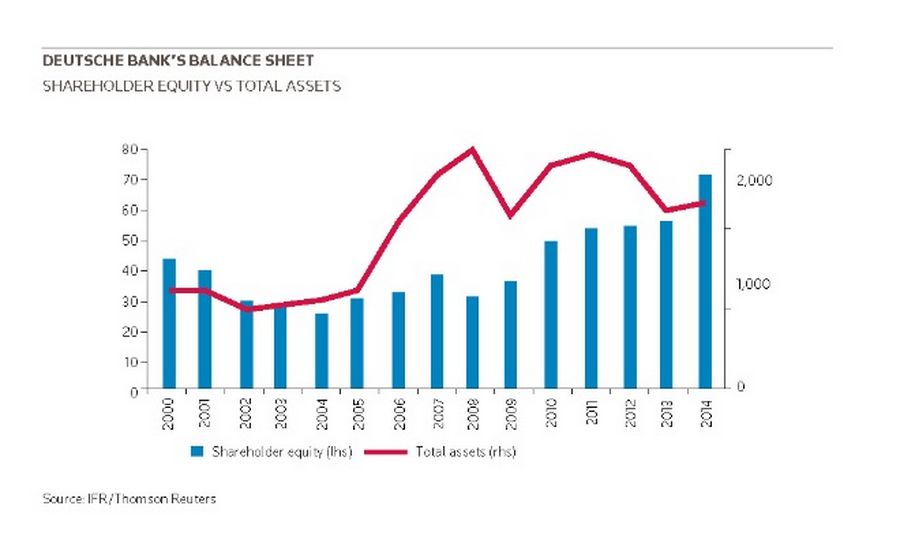

Even as others were slashing the size of their banks in the face of stringent new capital rules, the two did little to rein in Deutsche’s immense balance sheet, which was a staggering €2trn – bigger than that of any of its rivals and indeed larger than the annual economic output of most of the nations of the world.

Jain and Fitschen announced plans late that year to trim about 5% of the balance sheet – mainly by carving legacy business lines and assets out into a €122bn non-core unit – and selling a €5bn capital raise in April 2013. The two were confident that that would be enough to easily meet new rules on leverage.

They were spectacularly wrong. After the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision unveiled its methodology on June 26 of that year, senior Deutsche bankers admitted they had misjudged how severe the new restrictions would be.

The new rules measured leverage against the total assets of a bank, rather than using the diluted risk-weighted measure the industry had been pushing for. The biggest banks were worst affected – and Deutsche, perhaps, worst of all.

Wrong-footed and panicked, the two immediately ordered an overhaul of the bank’s strategy; they soon told investors that Deutsche needed to shed a further €300bn of assets. The impact on earnings would be in the hundreds of millions.

But the cuts were too little, too late. The non-core unit, designed to give the “core bank” breathing room to grow and generate much-needed capital to meet the onerous new capital rules, ended up bleeding money instead. In its first three years, the unit racked up more than €9bn of losses – double the amount of equity the unit freed up, and double the total profit of the group in that period. Half of the assets were created by Jain’s former business under his stewardship, but the banker offered little in the way of apology.

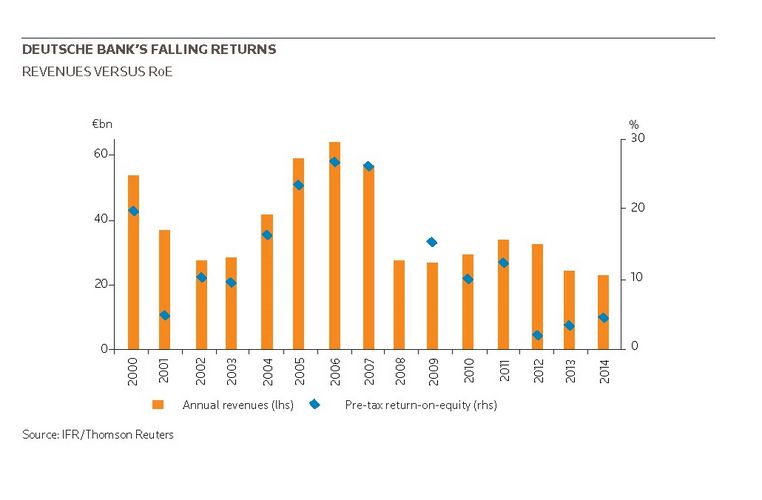

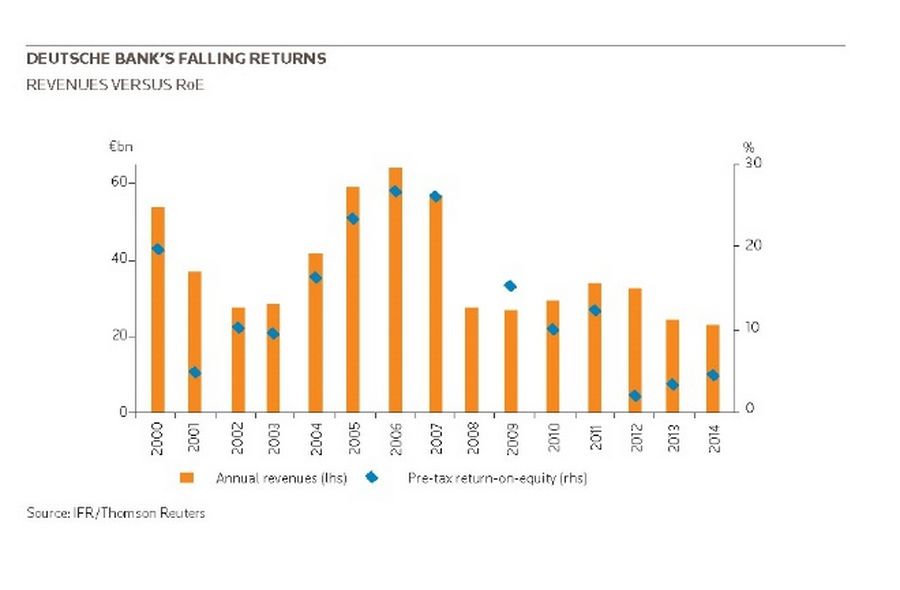

To make matters worse, a slowdown in fixed income trading – the bank’s main breadwinner – was beginning to hit the bank hard. The business had brought in €13bn a year at its peak, but by the end of 2013, when the leverage and non-core issues were beginning to ruin the firm’s capital-generation plans, it was earning just half that. Other banks under similar pressure began to cut deeply. UBS, one of Deutsche’s primary rivals in Europe, hollowed out its fixed income operations.

Yet Jain and Fitschen held firm and refused to make cuts in fixed income. The business had brought Deutsche huge success before the crisis, in large part because of Jain’s efforts. But it was also the business most affected by the new capital and leverage rules – and the two now arguably were failing to recognise that the world had changed.

They were also taking an enormous gamble. If Deutsche held fast – and could emerge as the last man standing in fixed income in Europe – then there would be huge rewards down the line. Deutsche could end up in the lucrative position of being the only European bank able to take on the Americans at their own game.

But capital wasn’t being generated quickly enough, as a jump to new European Union CRD4 rules in January 2014 showed. Other, better-capitalised firms had made the transition earlier. But Deutsche, seemingly reluctant to allow its capital ratio to fall any further, delayed stating its accounts under CRD4 until the last possible moment. Overnight, RWAs rose to €373bn under CRD4 from €300bn under Basel 2.5 rules – a 24% increase that forced Deutsche to find more equity to keep its ratio stable.

By Spring 2014, investors were becoming impatient. With revenues sliding and capital accrual plans seeming increasingly optimistic, Jain and Fitschen were under intense pressure to slash the investment bank and the resources it consumed. Once again, they dug in their heels. The two men chose to dilute shareholders – for the second time in just over a year – with an €8bn rights issue. That gave the bank a cushion. Within just five weeks, however, the cushion had been eroded, due to continued weakness in fixed income as well as further tweaks to the bank’s internal models to comply with new rules.

The higher equity base and sliding profits had a devastating effect on returns, which during Jain and Fitschen’s three years in charge sank to levels not seen in a decade.

“As an industry we have saved huge amounts on the cost side over the past few years,” Colin Fan, co-head of the investment bank, told IFR last year. “But at the moment shareholders aren’t reaping those gains. Much of that money is going towards litigation, fines, ongoing investigation work, implementing regulations and the like.”

The latest overhaul announced in April, during which Jain and Fitschen agreed further cuts to the balance sheet and costs and the exiting of some businesses – but also even less ambitions for return-on-equity to 10% from 12% previously – were clearly the straw that broke the camel’s back.

As Hans-Christoph Hirt, a director at shareholder adviser Hermes Equity Ownership Services, told the recent AGM: “The reshuffling of chairs didn’t go far enough.”

gareth.gore@thomsonreuters.com