IFR ASIA: Welcome. Michael, where are we in the Asian credit cycle at the moment, and do you think that’s justified?

MICHAEL TAYLOR, MOODY’S: We’ve been saying for several years that Asia has some pretty fundamental credit strengths, and I think that view has been borne out by events over the last few years.

We believe those credit strengths are still there, and we’re not expecting to see any kind of major negative credit event in the region. But we think that those strengths will be increasingly tested as the environment has become more challenging. There are several reasons for that, and one of those is obviously much greater policy uncertainty.

In this part of the world we’ve become used to having to speculate about the direction of Chinese policy. We haven’t really had to do that the same on the other side of the world.

It is clear that there’s a lot of policy uncertainty around at the moment. We don’t know really what the direction is going to be under the Trump administration, and that situation is leading to a lot of uncertainty in the market.

Now how does that have a credit effect? Well, our primary focus in the region relates to the risks of rising protectionist pressures. Again, we don’t know whether that’s actually going to play out, but rising protectionism is certainly a risk to the region given that many of the economies in the region still have quite high export dependencies.

We’ve seen Asia grow very strongly over the last 30 years on the back of globalisation and a more liberal global trading regime. If that goes into reverse, what is the impact going to be on Asia? That’s something that we’re very much focused on.

Then there are some shorter-term issues in terms of market volatility. Has the market priced in the US Fed’s likely action? May we see a steeper series of interest rate rises from the Fed than the market’s currently expecting? That could have an impact.

In Europe, concerns are around trade and politics. I think the extent to which Asia depends on demand from the European Union is often underestimated. It does play a significant role for a number of Asian economies. And if we had some kind of shock materialising as a result of European elections this year – of which there are quite a number – that will also have a spill over effect in terms of market volatility.

Our basic view is still that Asia’s credit strengths are in place. This is still one of the fastest-growing regions in the world. If you compare many Asian sovereigns to sovereigns elsewhere in the world in terms of debt dynamics, the situation looks stronger in Asia. We have strong growth, and a relatively good government balance sheet. Central banks have been willing to allow currencies to take some of the adjustment, which again is a big difference to 20 years ago.

There is still scope for additional monetary and fiscal support in several countries around the region if we started to see a slowdown. So those strengths are there, but I think if you look at all the risks, they’re certainly weighted towards to the down side.

IFR ASIA: Have people been broadly surprised on how markets have reacted under the Trump administration? Things seem to be going very well! Dilip, what’s your view on where we’re going?

DILIP PARAMESWARAN, ASIA INVESTMENT ADVISORS: As Michael was talking, I was thinking that when we talk about Asian fixed income as an asset class, the glass is always half full. Sometimes it’s at 40%, sometimes it’s at 60%, but it’s never the fullest and it’s never empty. I feel that of late the water has been going down in the glass.

There are a couple of reasons. One is China. Michael talked about the risks that could come from the US, from protectionism, and from Europe, but there is also China. The consensus seems to be that China will grow 6.5% or so this year and then slowly wind its way down. If something happens to that view, that’s an Asia-based risk.

Secondly, when you look at corporate balance sheets, a lot of them have been levered up in the last three or four years. Now that’s again a purely Asian risk. Thirdly, there is the valuation. Given the strengths and the challenges that Asia faces, I think valuations have gotten far ahead of themselves, particularly in high yield but also to some extent in investment grade.

It is still liquidity that’s driving markets, and issuers are of the opinion that they should take the money when they can. Who knows what’s going to happen? It’s not about whether we have two or three rate increases this year; it’s more about the non-priceable risks. What might Trump do? What might Europe do? What might happen to the Chinese economy? So I think the issuers’ mentality is to take the money when it’s there.

IFR ASIA: Arthur, let’s ask you then: Are investors getting a fair deal at the moment for the risks that they’re taking on?

ARTHUR LAU, PINEBRIDGE: I guess it depends what kind of fixed-income investor you are asking. I agree, as Dilip and Mike described, that the current scenario may not be too friendly for investors looking at short-term opportunities. Judging from what we see, actually the longer-term, traditional fixed-income investor quite likes the current environment.

In the past cycle, interest rates were so low, so it was very hard for them to find good enough investments to back their liabilities or their products. Now rates have risen, and that makes their life easier – as long as there’s no sharp uptick in inflation. The current environment is actually quite conducive, in my view.

Of course, valuations are very stretched, but the Asian bond market actually offers a very good Sharpe ratio because the volatility is very low. This asset class compares very well with the US based on the volatility on a total return basis. It’s not purely about yields. We have seen even European investors increasingly looking at the Asian market.

I think fundamentals are quite steady. The downside risk certainly is higher than the upside in my view because of the policy uncertainty – be it in the US or in China. That is the big risk in the market, but basically we are paid to take risk.

Dilip mentioned the leverage. Apart from the high-yield sector, I don’t see any particular concern about the high leverage at the moment – especially if growth is picking up.

The trouble we have is about the valuation. The valuation is not super attractive, so you really need to look for transactions that are more conducive than others. You need to stay away from the sectors that may be laggards if the market continues to perform. If you talk about the Sharpe ratio, we try to avoid those sectors with a lower Sharpe ratio.

WILLIAM FUNG, AMTD: I share a similar sentiment to Arthur with regards to valuations. Looking at high yield, today’s Single B credits are probably talking about 6% or 7% yields. If you’re lucky you’ll get 8% or 9%, but those credits were in the double digits two or three years ago.

I think the Asian market is much more technical than the more developed markets in the US and Europe. In our markets there are a lot of momentum trades, and there is a lot of Chinese money that has been increasing in the past few years. If you’re a European or Japanese investor you’re facing negative yields, so looking at Asia is very attractive. For US money managers, Asia may not be so appealing.

A lot of us, including ourselves, have seen a lot of influence from Chinese clients. They are obviously dictating quite a bit of market performance in the past couple of years and how it will perform in the next two years. Capital controls are limiting the impact, but there’s still a lot of money from Chinese clients that is bidding up all these Chinese credits. You think they’re expensive, but there’s still money to be put to work, and it will only get more expensive if you don’t buy now.

The primary market has obviously been pretty good. We have seen a lot of high yields deals perform very well. Single B debt pricing at 6%–7% still trades up 2–3 points in secondary. There’s still ongoing buying from Chinese accounts or private banks.

Valuations obviously look stretched, but I think it’s situational. At the moment we still see pretty good value in some high yield credits and some investment grades. Obviously you need to pick your fights, but we see the deals as fairly positive on this.

ALAN ROCH, ANZ: We’ve mentioned the concerns after the US election, and the market did get quieter in that period as people were worried about fundamental shifts in policies. The reality is we’ve had a very benign market environment so far this year, 10-year Treasuries have traded in a 25bp–30bp range. We haven’t had the type of rate volatility that people expected.

We’ve had a great bull run in equities, whether it’s in the US or here in Hong Kong. So the markets are not really seeing the negative ramifications so far. To go back to Trump, his restatement of a “One China” policy relieved the market.

To William’s point, one of the main differences when we do new issues here in Asia versus elsewhere is the type of investors who place big orders and support deals in secondary. A lot of the local payers have what we call Asia dollars, and are to some degree less sensitive to what could happen elsewhere.

So the risk of an exodus of dollars from the region back to more developed markets is less of a concern than perhaps it was in the past.

IFR ASIA: So it’s a pretty good time to be a banker, isn’t it?

HAITHAM GHATTAS, DEUTSCHE BANK: Absolutely. If you look at Asian credit markets, clearly you have structural growth in many of the underlying economies which is driving the need for debt capital and driving demand from an issuer standpoint. Corporates want the access, they want deeper liquidity pools. They are growing, they want access to that capital.

More importantly – and it’s been touched upon already – the evolution of the Asia buyside universe is incredibly important. William mentioned the greater demand and flows from Chinese investors, and you’ve also seen regional funds, hedge funds growing dramatically over the past few years.

The ability to raise financing within Asia has dramatically improved, and that gives an issuer certainty that it can access a deeper pool of capital.

We’ve seen the overall G3 market more than triple in size in the past eight years in Asia. However, I would almost say that despite that enormous structural growth, the amount of money looking to be deployed from traditional fund managers, private wealth and newer outbound funds is still at this point overwhelming the pace of supply.

IFR ASIA: To what extent is it distorting the market? Is there a risk that there’s just too much money chasing too few assets?

HAITHAM GHATTAS, DEUTSCHE BANK: If you compare Asian markets to their US counterparts – whether it’s investment grade or high yield – we are still a long, long way away.

In many respects Asia’s debt capital markets are still at a nascent point in their development, and I think it’s only natural that we’re going to see some ups and downs. We’re going to have periods where there’s more supply than demand and vice versa.

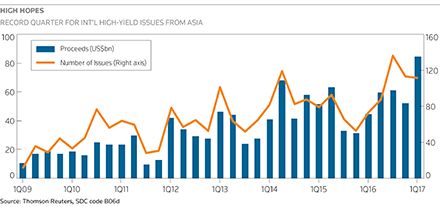

Right at this moment, yes, it is a little bit of a sweet spot for the markets. You have a fairly benign environment: volatility is low; Treasuries are range-bound; technicals are very strong. High yield issuance in Asia is up 300% year on year. There’s really no pushback at the moment.

Europe typically is four or five times the size of our market, but this year to date the two have issued about the same amount of paper. So, yes, the current environment is very positive, but as you’ve heard from Arthur and William, investors still see value in it and that goes somewhat to the positive fundamental outlook that investors have on this region.

ALAN ROCH, ANZ: It’s obviously positive that our markets are increasingly being supported by money within the region. Investors in the region have a better understanding of local credits and, to Arthur’s point, the Sharpe ratio in our region is actually lower.

I don’t think it’s a matter of too much money chasing the wrong assets at the wrong levels, otherwise we would have experienced more volatility than in other regions. I think it’s more likely to buffer any exogenous shock just by virtue of the increased amount of money at the disposal of the markets.

Again, when you look at US$200bn of annual issuance in dollars from Asia, it’s a small number in the context of Europe or the US.

IFR ASIA: I remember when US$40bn in Asia was a good year.

MICHAEL TAYLOR, MOODY’S: Just to follow up on one of the points that Haitham made on the importance of the regional liquidity pools. We’re certainly seeing that from our side as well. One point that does deserve reinforcing is that the level of market development in Asia is clearly not at the same level as it is either in Europe or in the US.

From a ratings perspective a lot of our outreach is about explaining to investors what is a credit rating and the role that it plays. That is a market development opportunity for us, but it’s a process that my colleagues in Europe and the US probably don’t have to go through. Here, we’re still at that sort of market development stage.

AVINASH THAKUR, BARCLAYS: The Asian markets are coming of age in terms of being self-supportive. The first deal after Trump’s election globally was in Asia. An Asian issuer going out the very next day after the election is something we wouldn’t have seen even two years back because Asia was more dependent on investors in the US and in Europe. Now we have a lot of liquidity, especially from the Chinese investors and foreign investors who have set up big operations in Asia. You can do a deal just based on Asian liquidity alone.

IFR ASIA: We’ve seen a lot of US dollar trades where there’s no US involvement whatsoever, and very little European participation.

AVINASH THAKUR, BARCLAYS: In fact in a lot of the recent transactions now we don’t even go to London for our roadshows. It’s only Singapore and Hong Kong. So that shows that you don’t really need any outside funding. We can be self-sufficient here in Asia.

From the supply perspective I agree with some of the comments so far. But I disagree with the fact that Asian markets are getting very levered. I don’t see that. When you look at most of large corporate balance sheets, they’re sitting very light. And if you look at the size of the credit markets compared to GDP in countries like China it’s still a long way to go before they get anywhere close to where the western world is.

So I see a lot more activity coming out of these markets. Our research also expects about US$200bn of supply but if you look at the GDP of this region, US$200bn is minuscule. Asia is still largely a bank market, and the transition to the bond side is happening over time. I won’t be surprised if Asian markets in the next five years are almost 40% of the global markets. We are less than 20% right now. I see that going up to 40% over the next five years.

ALAN ROCH, ANZ: Just a quick stat while we are talking about the Asia dollar. So far this year only 15% of dollar deals from Asia have been in 144A format. If you disregard the sovereigns, that percentage gets chopped down. That reinforces the point about who is holding this paper.

ARTHUR LAU, PINEBRIDGE: I think one important point to understand is that the investor diversity in the Asian market is similar to other developed markets. It’s not just institutional, I’m talking about retail and private bank clients. After the financial crisis in 1997 in Asia or the credit crisis of 2008–09, people realised that fixed income actually is a very viable asset class in their portfolio, unlike the long Asian bias for equity.

So you actually have a growing investor base chasing an asset class that is not growing as fast.

I think that is a fundamental structural shift.

People think that the fixed income market is

doomed because of rate rises or volatility, but I was joking with some of my colleagues about our longevity in the industry and I’m still around! Sentiment has changed, and people are chasing steady incomes.

AVINASH THAKUR, BARCLAYS: That’s likely to happen as the economy starts to mature. We’ve talked about China growing at 6.5% and the concerns around that, but just imagine 6.5% in a global context. It’s a good growth number!

The markets are getting more mature. I’m not worried about any of the known risks about China slowing down or issues as such as what happens with the elections in Europe. I think only risk to the market will be in terms of something unknown – if we are again hit by something which nobody has foreseen.

ALAN ROCH, ANZ: Maybe an additional point about liquidity. We’re definitely seeing Asia buyers now looking elsewhere. We’re seeing that now in Australia very clearly. They look to buy investment-grade bonds in Reg S-only format in Australia, that’s a new theme. We’ve seen non-Asia bank capital deals being done with strong Asian support. We have Taiwan buying US corporate in the Formosa market. We saw a financial institution yesterday doing a good Singapore dollar deal. So this investor base is not only focusing on Asia, it’s also looking elsewhere.

IFR ASIA: Calling a top is always tricky, but we’ve had some top-of-the-market trades recently. You think about the Road King fixed-for-life perpetual, or the high-yield bond from Buma, which relies on a company that’s in default for half of its revenues. These are aggressive deals, aren’t they?

WILLIAM FUNG, AMTD: It’s also about the availability of options. If you have a fixed income fund and you have inflows, you cannot be sitting there with 10%, 15% cash. You still have to invest. To Arthur’s point again, we’re paid to take risk. If you’re just going to buy US$200m in a private placement and sit there until maturity then our investors don’t need us. They can talk to the issuer, strike a deal and get a 6% coupon from a Chinese local government vehicle for three years.

EM funds are still seeing inflows, and Asian fixed income in fact has been performing very well in the past two or three years. So a lot of us still have cash to deploy even though things are toppish, but it’s not that we have a lot of options.

Liquidity in Asia is still very thin. Everybody is chasing the same thing. It’s always one way, with everybody buying the same two or three bonds. The global banks have their hands tied in terms of making markets, so you have one pool of Chinese money chasing Chinese credit and everything moves one way. It’s hard for the market to normalise that.

HAITHAM GHATTAS, DEUTSCHE BANK: Steve, you cited a few transactions. Clearly, there is a reach for yield. The supply-demand dynamics that are currently being exhibited in Asian markets – in particular in high yield – show there is this huge amount of liquidity that is available and this need to invest that William talked about, and less and less product able to deliver yields of 7%–8% plus.

That obviously makes for a favourable environment for issuers that may have more challenging credit profiles, or may be looking at more challenging structures.

On the other hand, these deals are getting placed very successfully, which might be slightly surprising to market participants on a fundamental basis but again seems to demonstrate the current insatiable appetite for yield.

AVINASH THAKUR, BARCLAYS: One interesting point about Asian markets compared to what’s happening in the US or Europe is that the duration-adjusted supply in Asia is still very small. That plays out in the yield, and that plays out in everything that investors do. Asian issuers are still borrowing at five years, or 10 years in rare cases. If you look at the US markets now, issuers are going out to 15 to 30 years or even longer.

DILIP PARAMESWARAN, ASIA INVESTMENT ADVISORS: Talking about liquidity, some people mention the support from private banks. I’ve been maintaining a database of all new issues and I think the allocations to private money reached its peak three years ago at about 16%. Since then it’s fallen to single digits. Last year it was 7%. So I don’t think that’s really the one that’s supporting liquidity and demand for Asian bonds. On the other hand, Asia last year subscribed to 75% of all new issues, up from 65% the previous year.

What the data doesn’t show is the role of China in all this. On the supply side, 60% of dollar bonds from Asia last year came from China. On the demand side, I think a lot of that is from China as well, as William mentioned. A lot of LGFV bonds have been placed within the Chinese bank universe.

The growth of the Asian dollar bond market is making us believe that it is now maturing and has enough liquidity to support its own issues. But if you take China out of that equation then I think the picture is not going to be that comforting.

MICHAEL TAYLOR, MOODY’S: Has there been a noticeable impact on the flow of Chinese money as a result of capital controls?

ALAN ROCH, ANZ: That’s a question we ask ourselves as well, and something we monitor. So far this year we are not seeing this at all in the new issues that we’ve run. The level of support that Dilip describes is very much still the case today.

HAITHAM GHATTAS, DEUTSCHE BANK: In a way the uptick in offshore issuance is also being driven by the reversal in conditions in the onshore markets. Go back 12, 18 months and you have extremely compliant onshore markets, with funding levels way inside what you can achieve in the US dollar markets even on a swapped basis. Since then you’ve seen a complete reversal, and that has obviously driven Chinese borrowers offshore.

It’s also interesting that Chinese borrowers now have to formally seek permission to come to the offshore markets. The NDRC approvals do seem to mean that we’re avoiding some of the situations that we had a few years ago, when you could have four or five borrowers in the market on any one day. We saw this type of market crowding when conditions were very good. So arguably a more measured and steady flow of issuers is helping the structural dynamic of the market.

DILIP PARAMESWARAN, ASIA INVESTMENT ADVISORS: In the last two months, local Triple A yields in China have gone up by roughly 100bp and local Double A yields by about 150bp. Twelve to eighteen months ago, many offshore borrowers – property companies and so on – were voluntarily raising money onshore because funding was cheaper there. Now it’s the reverse.

AVINASH THAKUR, BARCLAYS: I think regulators in China this year will be much more open to external borrowings. I think a lot of what happened with the NDRC and the gatekeeping last year is going to change this year. We are already seeing evidence of that.

The NDRC is very focused on getting the right kind of issuers out, so they will encourage the large state-owned entities to go and borrow more in the dollar market.

IFR ASIA: When we talk about China buying China, how much of that money is already overseas? The Chinese banks have raised a lot of international money that they need to reinvest.

ARTHUR LAU, PINEBRIDGE: If you’re talking about the Chinese banks as investors, of course, they need to invest. I understand the Chinese banking community is also actively involved in the debt market, but they are focusing on shorter tenors than we are – like up to five years. Some banks also focus on credits where they are already lending money.

You can see that strategy as part of the onshore-offshore dynamic. There are many factors that influence this, and some are more relevant to particular sectors.

I mean what Dilip is saying about the onshore curve rising is partly because the central government is encouraging more defaults. It is a natural tendency that credit spreads should rise, and I personally think that the credit spread has not risen enough to compensate for the risk.

At the same time better companies will come to the offshore market, and it’s a part of the reform process in my view. The issuers need to learn about how the international capital market functions, and at the same time the central government also want to leverage this international experience to bring the domestic market more in line with the international standard. I think in that perspective it’s a positive.

DILIP PARAMESWARAN, ASIA INVESTMENT ADVISORS: Steve, you mentioned that there is enough liquidity in the Chinese banks, and so there’s no problem for Chinese issuers to issue offshore bonds. That is true, but it also distorts the credit selection a little bit. Look at the unheard-of LGFV names that have come to market. Would international investors have bought all these bonds without the Chinese banks’ support? So the credit selection I think gets a little bit distorted here.

ALAN ROCH, ANZ: On the LGFV point we’re witnessing a little bit of a change in investor appetite. For sure the foundations of these transactions lie with the appetite of Chinese banks and with Chinese money, but as these bonds make their way into various indices, we’re starting to see funds participate in those transactions – selectively, but more so than one would have thought.

AVINASH THAKUR, BARCLAYS: I agree with Alan on that. Late last year there were a lot of LGFVs issuers who came to the market because they had to get a deal done before their approvals expired at the end of the year. At the time, the market was slow, so those were supported largely by Chinese investors. But when we look at the LGFVs this year we have very broad-based support.

Some of them are very good credits. If you do a fundamental analysis of the credits, there’s no reason why international investors in the long run would shy away.

IFR ASIA: There are definitely more defaults in China now. Michael, here’s a question for you: when you look across the Chinese issuers that you rate, is there a markedly higher default risk today?

MICHAEL TAYLOR, MOODY’S: Well, what we’ve been saying for some time is that we expect credit to become more differentiated. A couple of years ago there was a view that basically all Chinese issuers would be supported. We don’t think that really holds anymore.

When we look at default risk in China, it’s really to what extent do we expect these credits to be supported. The way that we’ve looked at it is first of all how close is this credit to the central government? There’s a difference between a central government SOE in a key strategic industry and an SOE that’s owned by a provincial government or one of the lower-tier regional governments.

Then there’s also a question in terms of what sort of industries are they in, which sort of sectors are they in. Again, if we’re talking about an SOE that’s in a key strategic industry, we still expect high levels of support. If we’re talking about an SOE in a commercially competitive sector or a sector in which the authorities are now trying to reduce overcapacity then the default risk is higher.

Our view is that there’s a much higher likelihood of default as you move through the lower tiers of government and into more competitive sectors. The whole policy has been towards trying to reduce implicit guarantees and introduce more market-based principles.

IFR ASIA: When you look forward, how confident can you be that that is not going to change? Those industries now facing overcapacity were key sectors 5 or 10 years ago.

MICHAEL TAYLOR, MOODY’S: I think we’re confident enough over the time horizon of our ratings, which is usually 18 months to two years. Obviously it’s a very fast-changing environment, and over the last several years there have been a series of policy announcements with a direct impact on likely government support.

Right now we are seeing a fairly clear direction in terms of expecting more defaults and less support for selected industries and for selected sectors. That much is clear, and that really does change the way that the market has thought about China credit. Until a couple of years ago I think most investors expected the Chinese government to support everything.

ARTHUR LAU, PINEBRIDGE: I think last year the central government reiterated that that was no longer the case. For some of the new LGFV loans or bonds, you should not assume that there is a guarantee or an implicit guarantee. Buyer beware, basically. I agree that some of the LGFVs actually have a viable business model. They have cash flows. For those you can check the independent credit assessment rather than buying it because of a government guarantee.

IFR ASIA: How much do you worry about policy changes? How far ahead can you look?

ARTHUR LAU, PINEBRIDGE: I’m sure all these gentlemen around the table have enough experience to know that Chinese policy is always changing. That’s a risk you face even if you’re not investing in China.

To view all special report articles please click here and to see the digital version of this report please click here.

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email gloria.balbastro@thomsonreuters.com.