IFR Asia: Alexi, maybe this is a question for you. How do you get around some of the investor concerns when you want to encourage people to go to the international markets?

ALEXI CHAN, HSBC: Yes, I think there are some very interesting issues around the challenges of developing these local markets. What’s very important for international issuers, underwriters and investors, first of all, is the consistency of the regulatory and government framework behind these markets. It clearly can be challenging if there are different views on withholding tax, different views on whether local investors can or can’t participate in the markets, which can make this more challenging.

We would absolutely like to see – and we are seeing, I think, in certain markets – the authorities taking a concerted step to help build international participation in these markets, recognising that perhaps some of the early requirements on things like withholding tax may be needed to be more flexible to build the markets.

We’ve talked quite a lot about India. With China, we are seeing some very encouraging progress in the opening up of what is already the world’s third-largest capital market, the onshore RMB market. There, the authorities have taken a number of steps to facilitate access for international investors. The early steps were very much quota-based, the QFII and RQFII programmes, and we’ve had a number of further schemes introduced. The CIBM [China interbank market direct access] was, if you like, the third iteration. Most excitingly, in the middle of this year we had a new scheme called Bond Connect.

Bond Connect effectively allows international investors to get access to the onshore market in China through their existing infrastructure in Hong Kong, without the need to use any quotas or have any infrastructure onshore.

The precursor to this, Stock Connect, was set up with a northbound and a southbound element [allowing money to flow into and out of China]. Bond Connect has started with a northbound route, and our experience in the transactions we’ve been involved in is that we’ve seen a significant uptick in participation from international investors and we think that’s set to continue.

I think there’s a lot of cause to be optimistic. Clearly, for any country to have a sustainable capital market, we do need consistency of regulatory and public policy. We need underwriters to be able to provide liquidity to the international markets, and that’s something we’ve worked hard on with Monish and his team, for example, on Masala, and on Dim Sum before that. I think liquidity provided by market makers is another factor that will support the development of these markets. For HSBC, that’s something we’re committed to across the Asian region.

IFR Asia: There are two models here for internationalisation. There’s the offshore market, with Masala, Dim Sum bonds and so on. Then you have Bond Connect, where international investors get direct access into the local pool. Which one makes more sense?

MONISH MAHURKAR, IFC: Like I was saying earlier, I think the domestic market has to be the primary driver. The offshore instruments are a bridge to a full scale, fully-open, free-flowing market which connects onshore and offshore players.

I can see the gentleman on my right is concerned that Masala, from your perspective, may not work, because if you have direct access to the domestic market, why would you not go there? That’s where the liquidity is, that’s where the major buyers and sellers are. But then, when we launched the Masala bonds in late ’13, early ’14, to our surprise at that time, there is still a large segment of investors for whom there are certain other criteria.

I’ll just name two or three of them. One, many of the global investors still have fairly stringent ratings restrictions, so they won’t buy paper below a certain level, so it helped that we were Triple A. It doesn’t necessarily help an Indian company looking to go into Masala, but then later on, as things picked up, there was a market for that credit level as well.

A second factor that came to light is that many investors prefer the standard international GMTN format or Euroclear instruments, which may not be available domestically. A third could be simply administrative. There are more sophisticated fund managers, perhaps such as yourselves, who are willing to go through the registration process, understand the local market’s peculiarities and work within that. Then there are those who just won’t have the appetite to do that and would just like a standard instrument in the international market.

So, there is a place for both, and I think the Dim Sum bond market played a similar role. We were beneficiaries again – working with partners such as HSBC and other banks – where having access to both markets gave us the advantage to see which one worked, from a pricing perspective, better at any given point in time.

We’ve had, over the years, situations where the Dim Sum market offered better pricing than the domestic market, and now currently there’s more favourable pricing in the domestic market. So, I think in the process of developing these markets, we have to keep an open mind. There is no easy, linear, straight-forward process to developing bond markets from our experience. I think one needs to be flexible.

IFR Asia: I think Invesco has a presence in the onshore Chinese market already, but a lot of investors have been holding back. Where is that going to end up, Arnab? We’re going to have to get more international money in there somehow, aren’t we?

ARNAB DAS, INVESCO: Yes. Invesco has a joint venture in China, Invesco Great Wall in Shenzhen, and we also have an operation in India, Invesco India in Mumbai. So, we have domestic operations, domestic clients, and domestic assets, and some amount of international clients flowing through those operations as well. Like Loomis Sayles and others, we also participate with foreign client money in Masala and Dim Sum, and also directly in the domestic market.

I think we have to think about this in the context of the capital control regime. What’s happening, I think, is a gradual sequencing in that both countries at are different points in the sequence of developing their domestic capital markets and gradually reducing the barriers to capital flows. When you start from a situation where you have capital controls, you have, in effect, a distorted capital market.

Not to spend too much time on the Indian case, but in India, the equity market is actually quite open, and the bond market, as we’ve been discussing, is relatively closed. I personally think that makes the equity market more expensive, and the bond market maybe at times more expensive than it would otherwise be, in the sense that yields are lower and the equity risk premium is lower. You have a lot of capital that’s trapped in the domestic market, and the portfolio preferences of the rest of the world for exposure to India are diverted from bonds into equities.

So, many people justify the rich valuations of Indian equities on the basis that India is like a growth stock, which probably has some merit, but I think we have to recognise that there are these distortions.

In the Chinese case, it’s very different. We have an enormous amount of wealth and financial assets with resident Chinese investors with something close to 100% exposure to China, who probably want a considerable amount of diversification. The rest of the world has relatively little exposure to Chinese issuers – certainly onshore, and to some extent through offshore and hard currency issuance. So, there needs to be a swap of these exposures. One of the critical questions posed by Bond Connect and Stock Connect is how is that going to work? It’s a critical issue for the Chinese financial system, it’s a critical issue for the Chinese economy, and it’s a critical issue by extension for the world economy because China is so big.

I think we’re in a gradual process of feeling out the right sequencing and using examples from history, perhaps somewhat adapted for Chinese circumstances and Indian circumstances, because it’s fairly clear nobody is going to flip a switch and give up control and roll the dice come what may. It has to be managed in a very careful way.

If you look back through the history of quote-unquote ‘emerging markets’, you see some very good cases of this kind of opening where it’s worked very well. And you see, of course – not just in emerging markets, but pretty much throughout the developed world – where you’ve had financial deregulation and liberalisation, you typically get a financial crisis, or at least some financial dislocations after that.

I think the sequencing, going gradually, and along the way dealing with all these frustrations, I think we have to live with that.

IFR Asia: Bill, on India, when you look at Masalas there and the internationalisation of the currency, it hasn’t been a completely linear process there either, has it?

BILL FOSTER, MOODY’S: Not at all. I was saying earlier it has fits and starts. Just this past summer, you saw that happen. Basically, the regulators closed off the market in June, July, and then in September they reopened it but in a different window with more restrictions, and you have to go to the RBI to request access to the market. For people that know India, this isn’t really a surprise. Ultimately, it’s a controlled market.

The RBI is understandably very concerned about capital flows, volatility, and how that impacts the balance of payments and the exchange rate. They don’t want to be caught in a situation where they have to be on the back foot, which is understandable. The bond market domestically is a product of financial repression. It’s ultimately held by banks or large government institutions that don’t trade regularly and the yield curve is effectively flat.

There are a lot of sequential issues that need to be sorted out before, ultimately, something like the Masala bond market offshore can develop. They’d first have to be prioritised onshore.

IFR Asia: At what point does that feed into a sovereign rating? You’re bringing in more risks, aren’t you, into a closed economy?

BILL FOSTER, MOODY’S: Taking a step back, not necessarily in India but in general, you look at the capacity of the economy to absorb flows in a sustainable fashion. Obviously the external vulnerabilities and level of exchange rates, and how much is foreign currency debt relative to domestic currency debt matters quite a bit in terms of the vulnerabilities there, and the levels of debt and the capacity to assume more debt over time, and how sustainable that is at a very basic level.

Obviously, there’s a lot more that goes into it, but having a deep capital market that’s liquid and has a diverse investor base – both from institutional investors domestically and local currency, and potentially offshore as well in both domestic and foreign currency – is very helpful. But only if the sequencing is right, otherwise it’s destabilising and very risky. That’s documented very clearly. So those are things that we look at.

IFR Asia: Monish, perhaps we can get into some of the specifics now on your experience in opening up new markets. We’ve talked about Masalas, but there are a number of programmes, aren’t there, across this region?

MONISH MAHURKAR, IFC: Yes. The effort over the years has been to try and create programmes, customised to specific markets and countries, because regulatory frameworks do tend to be different.

In most cases, we try and go in and get a framework to be able to issue bonds within the local domestic market. So, for example, we’ve done this in Nigeria, we’ve done it in smaller markets like Rwanda or Costa Rica, we’ve done domestic Panda bonds in the Chinese market. Even in India, we experimented with a small, what we call a Maharaja bond, just to distinguish it from the Masala bond, which was a small issuance because the pricing didn’t quite work for us.

What happens in some of the domestic markets is that – and it’s not completely surprising – investors do not differentiate an international Triple A from the Triple A that they would associate locally with their own sovereign. In effect, given that in many of the markets we go in may be just about investment grade or even below, we don’t get the pricing advantage that we would like to see. It’s a real issue for us because, not being a bank, ultimately we’re only able to finance clients based on the cost of funding that we can access in the markets. If local banks have access to much cheaper deposits, then we might remain uncompetitive.

That’s the kind of challenge that you face. Secondly, there are also, at times, challenges in terms of just setting up regulatory processes, prospectuses, registrations, documentation, a standardised template for these things.

That, we feel, can be a multi-tiered effort, but I think the investment of that time and effort is worthwhile, because it helps to bring these best practices into the markets.

IFR Asia: When you put these programmes in place, how do you get around some of the regulators’ fears that all the money in the country will go to the IFC instead of their own companies?

MONISH MAHURKAR, IFC: It’s a good question, and sometimes we do have those discussions around this potential crowding out. We of course reassure our member country governments that, first of all, scale-wise, we are not talking about large issuances relative to most markets that we go into. Even for a small market like Rwanda, the size that we would issue, it’s more of a catalytic transaction.

It’s a demonstration, and it of course helps to finance some of our projects, but it’s not going to crowd out even a Rwanda sovereign, let alone a Chinese sovereign or an India sovereign, which is in a completely different league in terms of size. So, it’s not a concern in most places, but yes, in some markets, people still fear, partly because the discussions are ongoing that they are uncomfortable having a foreign entity coming in and issuing in that market.

ALEXI CHAN, HSBC: If I could just add a couple of thoughts to Monish’s comments. First of all, we have seen some interesting transactions where multilaterals or other Triple A or highly-rated organisations have come into a local market like the Masala market and subsequently done, effectively, a back-to-back financing with another issuer who may want to issue a Masala bond themselves, and where the supranational can act as the anchor investor in that financing.

I think those sorts of back-to-back transactions can be very helpful for market development.

MONISH MAHURKAR, IFC: An interesting point to what Alexi just said, is that the way we have deployed proceeds, for example, in the Masala bond, is actually one of the better examples of how, ideally, things should work. The framework for investing that money is under what we call our foreign portfolio investors licence, so all the financing that we do for our clients in India against our Masala proceeds is through asking our clients to issue bonds in turn. They issue domestic, what are called NCDs in India, non-convertible debentures – basically domestically listed bonds.

It also adds to the flow of product in the domestic market. Right now, we have invested in these bonds, but we can also offload and make them available in the secondary market.

IFR Asia: Eddy, do you think it brings in more investors? Does it crowd in?

EDDY STERNBERG, LOOMIS SAYLES: I was thinking as we were discussing, “Who’s come to the Masala market on the domestic company side?” It’s very, very few. I don’t know if it’s because the IFC is crowding out – I don’t think that’s the case. I think it has to do more with the cost of financing. The domestic issuers can get a certain pricing domestically. Once they come to the Masala market, there are all the issues around withholding taxes, which we would not have to pay as investors, but they would have to make up either in the yield or rebating the cost, or something like that.

All of a sudden, the Masala bond does not seem to be as attractive to issuers who can access the domestic market easily. We haven’t seen that many issuers, so I don’t know that it’s a crowding out, or it’s a cost, and that’s another reason why I dislike the Masala, or specific offshore investor markets.

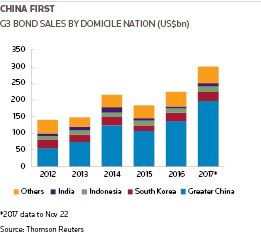

I’m also thinking of several things that we said here. One is, if you think of emerging market investors before you think of any other type of investor, there are some indices that we follow, especially when it comes to local currency indices. The most prominent one is the JPMorgan GBI-EM Global Diversified. Neither India nor China is part of that index. Currently, if you think of that index and you think of its market cap, it’s about US$1.2trn without those two countries. You bring those two countries and that market value is US$2.2trn. China brings in about US$700bn and India brings about US$300bn – not the exact numbers, but to round it up. It is huge.

We talked about Bond Connect, and we talked about the CIBM access – if I’ve got that acronym right. CIBM was moving very slowly, so they introduced Bond Connect, which makes things much easier, but China is still not part of the index. So, there is a problem. There are some details that have to be worked out. Going through Hong Kong may be easy, but it’s somewhat restricted. You’re only able to deal with one counterparty at that point in time. That’s great for the counterparty, and not necessarily great for us, so again, not many people are investing, not many people are ready. The index provider has not put China in the benchmark yet, and it’s not likely to do it this year – maybe next year if things open up.

I think the authorities there understand that they’re making progress, but it’s not as great as it sounds, at least today. The case of India, we talked about the equity market being very open. I don’t quite understand why the Indian authorities are not concerned about the inflows and outflows of equity investors into India. They say, “No, they are stable.” If I’m an emerging market investor and my index has 10% of its benchmark in India, will I not be stable? Will I not want to be there at least with 8% or 12%? Those flows are not huge.

Let’s think of it this way, in the investments benchmarked against this US$1.2trn index that I mentioned, the foreign investors only have US$220bn. It’s a lot of money, but think of India becoming 10% of that, it’s US$22bn. Part of it will be sticky, so I really don’t see that many inflows and outflows. Again, it’s a question of opening up a little bit more, making it easier. Skip all the steps with Masala, Panda, Dim Sum markets. They’re uncomfortable.

IFR Asia:I think a lot of people are expecting, certainly in China’s case, that bonds will be added to those indexes pretty soon.

EDDY STERNBERG, LOOMIS SAYLES: Last year, the index providers came around, did a roadshow, and asked, “Who’s interested and are you doing anything about it?” And we said, “We’re not, but it’s going to be 10% of our benchmark.” So, immediately after they left, we sent an email and said, “We would like to open accounts in China.” This is April of 2016.

Today, we’re having bi-weekly meetings to discuss the opening of the account. We’re nowhere close to that yet, so I don’t think that’s happening any time soon, despite Bond Connect.

IFR Asia: So, it’s not for lack of trying? It’s just the infrastructure is not there yet?

EDDY STERNBERG, LOOMIS SAYLES: That’s correct.

To see the digital version of this roundtable, please click here

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email gloria.balbastro@tr.com