IFR ASIA: Sean, do you see the Asia Pacific investor base differentiating like this? Is it going to be more expensive to issue a coal bond, for example?

Sean Henderson, HSBC: I think what we’ve seen is the mindset change around this market, from green bonds being initially seen as a niche product, where asset managers start a separate green fund and market that to a few specialist green investors, to now where ESG risk is seen as part of a much broader risk management framework by almost every single investor in Europe. TCFD, Article 173, and other similar initiatives are pushing everyone towards greater disclosure of their ESG risks, across every single fund, and this is hugely beneficial to changing the behaviours of investors across every single sector.

I think how that’s moving is quite interesting. You’re seeing rating agencies now putting ESG risk factors into every single rating that they look at. So it’s not just a niche product anymore. It’s becoming much more of a broad understanding of what ESG risks mean for underlying corporate behaviour, and forward-looking risk factors as Eric points out.

It’s all very well building a building now, but what’s the value of that building in 20 years’ time if you haven’t it built it to forward-looking standards? I think people are starting to realise that’s an important consideration beyond just the immediate returns.

So the idea of simply looking at green bonds, and how fast the green bond market is growing, is gradually shifting into a much bigger understanding of ESG risk and how do you explain that to your investors. We’re increasingly seeing investors who two or three years ago were asking, “Why am I buying a green bond? What’s so different about it?” are now coming to us and saying, “Actually every time I’m going out and pitching for a mandate to manage money for a corporate or a pension fund, the question is increasingly coming from them, what’s your strategy on ESG?”

The knock-on effect is you’re then seeing corporates starting to understand that they really need to boost their disclosures in order to appeal to these funds. You’re seeing a big drive, for example, in Singapore with the SGX launching guidelines and rules on sustainability reporting, with a comply or explain policy. The regulators are also getting on board, for example MAS’s initiatives to develop Singapore as a global hub for sustainable finance. I think the initiatives and the momentum of this is much bigger than people would realise if they just looked at the proportion of green bonds being issued from this region.

I definitely think this is a journey. As I said from the beginning, I think people initially thought, “Oh this is a great new product. This is going to boom.” Actually it’s much more complex than that. It’s much more broad-based than that.

IFR ASIA: Andrew, does more need to be done to standardise the greenness of loans and other weaknesses in the way that perhaps the reporting is done, for example?

Andrew Ashman, Barclays: At the moment, green loans are structured using a green loan framework developed by the APLMA, the trade association for the syndicated loan market in Asia Pacific. The whole rationale behind that framework is to standardise and encourage early adoption of the product.

In some areas, the framework is intentionally vague. I think as we see the market develop, we will see those frameworks become more detailed and more explicit in how green loans will be structured and administered.

At the moment we’re looking to drive the market and to build volumes and having a trade association such as the APLMA is an important element of facilitating that growth.

IFR ASIA: Eric, do you think that there needs to be more done to standardise ESG measurement?

Eric Bramoulle, Amundi: Of course. This is also a fear factor for issuers and investors. What guarantees the fact that I’m really investing in a green bond or ESG equity? There are plenty of working groups in progress, TCFD being probably one of the main ones. The central banks as well have played a major role because they have integrated in their mandate climate change as a standardised investment risk, and the message they have sent by doing that is a strong message to the financial community, which is that if we do it as central banks you should do it in the insurance, banking and asset management industries.

Again, this is about how to standardise this approach on climate-related risk in a taxonomy because without this it’s very difficult to go on to the next step which is the disclosure, and the reporting of the impact. After that there are two other sectors that are key for me. One is proper balance between the corporate world and the policymakers, because I see the corporate world have their duties and their role to play in this.

The last one is to have the government raise the awareness collectively for everyone. I think in Asia it’s still a little bit behind what we experience in Europe. There is a top-down approach that governments should be able to raise this awareness. Then at the end it will translate into sustainable savings in the long run.

IFR ASIA: Cedric, how are issuers using certification, and are there any weaknesses or any need for standardisation there?

Cedric Rimaud, CBI: The market already has the green bond principles from ICMA, the social bond principles that are also applicable for the region through the ASEAN green and social bond principles. The Climate Bonds Initiative has developed a taxonomy for the climate bond standards which indicates projects that are in line with the objectives of the Paris agreements.

We have a very big initiative in Europe right now to develop a Europe-wide taxonomy, which, when it applies to all European based institutions, will by default also concern banks that are in Asia and have operations in Europe. So this is actually a big step this year that is going to bring some standardisation across the market.

Like I said, some countries are trying to see if they should develop local guidelines as well. Malaysia and Indonesia have their own. I think there are benefits for them to follow the global standards.

In terms of verification there are a number of actors that are starting to provide those services. Prices have come right down. Initially the service was priced at US$100,000 to US$150,000, now it’s more like US$20,000, so it becomes less of an issue for issuers. Our certification costs are almost nothing as well.

So there are ways to provide this assurance to investors that the projects are aligned with the taxonomies. I think there’s no time to wait. I think the region is realising that there are some major issues related to climate change in Asia. The decision to create a new capital city in Indonesia is a testament of how critical this can be for a country. The haze going through South-East Asia is another one that everybody knows about and there are many issues that are really, really becoming an emergency. I think businesses, governments, and all of civil society is going to really quickly grasp this issue.

IFR ASIA: Sean mentioned earlier that green finance isn’t a niche business anymore. Eric, do you think that all asset managers are going to have to incorporate ESG measurements into their portfolios, whether it’s a green fund or not?

Eric Bramoulle, Amundi: I wish that in five years from now for a discussion around the same topic this room will be completely empty, because it would have become the norm, and that it would have been completely integrated. This is a step that Amundi took, and for me it’s obvious.

Why it is obvious? I was an equity portfolio manager myself. Over the last 20 years we faced so many examples of issues we could have avoided by integrating this strict criteria. It’s all about the collapse of Enron and the big crashes linked to governance and control measures that were not in place and that the governance criteria could have enhanced. When we look at the performance generated by the ESG criteria, most of the time the governance one is the one to matter the most, but the three are very interesting to follow.

IFR ASIA: Jayant, we’ve heard that ESG is in your DNA, and you can’t change your DNA, so how is green and sustainable financing going to figure in Olam’s plans going forward?

Jayant Parande, Olam: I think looking at the interest which has been generated within our lending institutions and banks, it will continue to play an important part going ahead as well. In fact, well before we issued the sustainability-linked loans, we had and continue to have a very good relationship with developmental financial institutions – which are naturally sustainability-focused – like IFC and ADB, AFDB, the European DFIs. Having seen us operate in emerging markets and having worked closely with them over a period of time, DFIs (and of course commercial banks) continue to be keen on more collaboration on ESG-linked financing.

We continue evaluating green / sustainable bonds and, at appropriate terms and pricing levels, we would be pleased to consider such issuances to supplement our debt capital markets programme.

IFR ASIA: Mike, what about Frasers, are you going to continue on the sustainable track now?

Mike Tan, Frasers: Yes, we will obviously continue on that track. The issue we sometimes face is internal. If we were to build a new residential complex or a new building, on our side we will try and push people to build it with more green features and then there will be “x” million dollars cost. Then they will ask me how much will we save from a financing perspective. I can’t really give them a straight answer that we’ll save US$10m because the green technology for your aircon coolers or double glazing windows. I can’t really say that.

The only thing I can say is to do it for the future, do it for the long game, and that’s part of the DNA. Even as developers, as asset managers, we will have to take a hit from a profitability perspective by investing in the future.

So it would be helpful if for example the regulators or even the governments consider at least for the building industry, for example, having a small tiny cut on the stamp duty for a new residential building that’s extremely green. That will be helpful. That would incentivise people to buy more apartments which are green.

IFR ASIA: Andrew, you’ve given plenty of green sustainable loans, do you see any benefits beyond cost, any intangible benefits for issuers that have gone down that road?

Andrew Ashman, Barclays: At this stage in the early development of the market any green loan that closes is receiving an oversized share of publicity in the business press. From an issuer’s point of view, if you want to be seen as an ESG-focused company, signing a green loan is a great way of gaining profile.

Sean Henderson, HSBC: If I can add a quick comment on that, I think it applies to bonds as well as loans. I think from issuers often the first question is how much am I going to save, and why should I do it?

On the loans it’s a little bit easier to argue with the banks who are perhaps a little bit further along this journey. When you go to the bond market, perhaps the institutional investor base still needed to go through this journey, and so the first potential issuers were saying, “How much do I save and what do I get from it?”

When they completed the journey, though, I think one of the biggest things they took away was how much they learnt internally through going through the process. Building a green or sustainable framework and understanding what the actual impact of your business is and your business decisions are, was probably the biggest thing they took away. It’s all very well to have a sustainability person sitting in the corner of the office who pops up and talks at your occasional strategy meetings. To have every kind of business head have to report on the impact of their business, to go into your reporting and to really have to measure and go to that level of detail is actually a critical part of the learning process for everyone else in the organisation.

Doing a green bond or a green loan forces the entire organisation to report in a way that they may have not done previously.

It might be less the case for companies like Olam and Frasers, for example, where it’s already part of their DNA, but I think for many other companies, doing a green bond or green loan puts it within the DNA of almost everybody within the firm as opposed to sitting only in one part of the strategy department.

Jane Yuan Xu, IFC: I want to add this point because I really see this journey among many of our clients. When we start asking for ESG compliance, it’s an enlightening process. Some companies already do things but they are not aware of it. By really identifying that and starting reporting, we’ll also get people to think that it’s not just for CSR, it also helps them with their bottom line.

In a lot of the manufacturing business, and even in the property development, there are certain things they can do that are not necessarily that more expensive. By doing that bit by bit you actually transform the business.

I think a very good example in my own experience, is when I first started looking at a cement plant investment 15 years ago, in China, when no one thought about using a heat recovery system. The company that we supported in cement were the first one to install the heat recovery system. When they went public in Hong Kong a few years later, one of the key highlights of the company is that 40% of their energy consumption on site is supplied by the heat recovery system. That makes them not just greener but makes them more cost-efficient compared with their peers.

Cedric Rimaud, CBI: We also see that at the government level for Indonesia, for example, through the two green sukuk that were recently issued. The Ministry of Finance is now acting with all the different line ministries to find projects to finance. That’s actually a very healthy discussion within different branches of government, which often act as independently of each other, to actually come together and source those projects.

We hear that a lot. In the Philippines also there is a climate change commission that is acting as the central point within the government to find those different projects.

So there’s a lot of things happening on the public side as well on the back of a sovereign bond issue.

IFR ASIA: I’ll just ask one final question to everyone before we take Q&A from the floor: what’s going to drive ESG bond or loan financing in Asia and should it be the issuers, investors or regulators that drive it?

Sean Henderson, HSBC: I made the point a little bit earlier but I think it really does take both push and pull. It really requires investors’ behaviour to change to really make a difference to incentivise issuers to do it. Likewise, it takes issuers to really be committed to the journey and understanding what the ESG risks mean for their business, improve their reporting and their disclosures so that investors can make sensible decisions. So it really requires both sides.

I think the regulators have been moving very quickly in this direction. I think Singapore has done a great job on this and has a large number of policies and development areas that they’re working on at the moment, but also other regional jurisdictions as well. I feel like it’s definitely heading in the right direction.

The big key for me, as I said before, is that I don’t think we should just think about green in terms of how much of the market is issued in green bonds as a percentage. It’s really about broadening the understanding of ESG risk as it applies across every investment decision you make, and the companies starting to incorporate ESG risk into every decision that they make going forward. I think it’s also about the short versus long-term goals that Mike talked about as well, and understanding and being able to measure the long-term impact of those decisions, and disclose and actively manage these risks as we deal with complex issues such as climate change. It’s a key part of being able to make better decisions for the long-term benefit of all stakeholders, rather than focusing on short-term profit.

Jayant Parande, Olam: I think it’s important to have a collaboration of everyone, whether it’s issuers, lenders and regulators, to make sure that we can have a vibrant green / sustainable financing market for bonds as well as loans.

I guess for issuers, it will continue to be important to focus on sustainability as a part of your overall business model as against trying to do it only if you’re getting any benefits. I think benefits will come along the way, whether it’s through lower pricing, or by way of recognition and validation, or by generating customer / supplier stickiness of a much higher order, or your bankers and investors wanting to have a closer collaboration with you.

I think these benefits will definitely follow. It is up to corporates to continue doing the right thing.

Mike Tan, Frasers: Actually, we do get some pricing benefits for doing green loans, for example. In the second year we did see some pricing improvements, as long as we keep to the benchmarks and the framework.

For us, that comes about because there’s greater and greater demand amongst the lenders. When you have a lot more demand than supply then you get better pricing.

I think philosophically we need to look at how we run a business, not just as returning profits to the shareholder, in terms of the old-style capitalism. The way we run it we are delivering a return for the stakeholders that includes the shareholders, the lenders, the customers and the partners that we have.

We take that approach, plus the fact that the new younger generation of millennials have different value systems. They don’t always look at profits or salaries as what’s driving them. They look at how the working environment is and how to improve the environment. I think inevitably we will move towards a more sustainable financing future. It’s just how we get there at a faster pace.

Andrew Ashman, Barclays: I think issuers, borrowers, lenders and regulators all have a part to play in growing the market. When I look over the last 18 to 24 months we have seen huge growth and the market really has developed very, very quickly.

Much of that development has been driven by the issuers. The trailblazers such as Olam and Frasers Property have come to banks demanding this product. I think the challenge now is to convince the next tier of corporates that haven’t been as engaged in ESG to approach the green loan market. So it is probably the banks that have to explain the benefits and why a company should be considering this product.

We all have a part to play but the banks in particular have a role in promoting the product to the issuers.

Eric Bramoulle, Amundi: This climate-related risk of partners and normalising investment risk processes across the board is a very strong factor but also on the philosophical aspect I feel really subscribe to what Mike just said. We believe in what we call Rhine capitalism, which has more social policies as opposed to the quarterly results-driven capitalism. We know for the last 40 years, if not more, that ESG is not neutral. To accept, we should combine more results-driven capitalism with some social aspect.

Switzerland, Germany and the Netherlands are the ones driving this type of approach. This is something we would like to promote going forward.

Jane Yuan Xu, IFC: I think it’s very important for all the governments to really stick to the commitment to COP21. Don’t change your course. At the same time it’s also very important for progressive companies like Olam and Frasers to share your successful stories. It’s very important to the third-layer companies to hear each of you say, “Hey, this is something not just for good PR, for doing good but it’s something actually profitable and sustainable,” and also the way you achieve it doesn’t depend on rocket science but is something everyone can do, if they care to try.

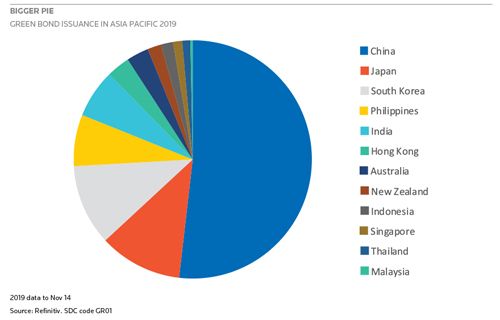

Cedric Rimaud, CBI: I think in South-East Asia there’s a tremendous need for capital to be deployed into climate-resilient infrastructure. Some studies show that there is a need of between two to three trillion dollars a year to invest in the whole region’s infrastructure. Yet it’s a region that is dominated by bank lending as we can see from the panel. The question I have is whether bank lending is sufficient to a company that grows. My feeling is that through the growth of the green bond market we are able to bring new sources of capital that can come in through the bond market and tap into all the reserves of capital in Asia and beyond that is available through private banks or some funds as well, ETFs and so on.

We really need some action from the government and from the regulators to facilitate that transition of capital from the private side to those projects. It’s very important.

AUDIENCE: A lot of forums speak of incentives for getting assets as a borrower, and as a financier. It’s the carrot and stick story. What are the business incentives that will force everybody into green financing?

Eric Bramoulle, Amundi: We had a debate recently about that: when do you stop the incentive and when do you start using the stick? I think it depends on the level of maturity of the topic. We are probably right at the turning point at the moment. I explained this example in France about companies who are disclosing their policy on climate-related risk policies and the ones who are not. It’s a kind of incentive and stick at the same time. If you won’t do it, everyone is aware that you don’t have any policy for that. If you do it you are in the green part of the room, but this takes many, many different aspects.

Sean Henderson, HSBC: I think it’s a very good point because I think there’s a risk, and this is where the whole comment around green-washing comes, with issuers potentially saying “if I’m 90% in an industry which isn’t green, but if I do one building or one business that is, I can do a green bond.” That’s obviously not okay because it really hides the big issue.

I think there eventually has to be some kind of move towards rating or understanding the ESG risk profile of each company, because otherwise the green bond is only giving investors visibility of a small subset of their business. I think that’s where I was alluding to, for example, the rating agencies starting to look at the issue of ESG risk factors. I think that’s also why article 173 is so progressive in France, because it’s forcing everyone to disclose exposures, not only at the individual financing and use of proceeds level, but also at the broader corporate level and then also asking every asset manager, how green is your fund?

Fund managers are also having to think “how do I rate my fund?”, then they have to start look at everything in the fund, not just saying they have 20% in green bonds but actually having to disclose whether they also have 30% of their funds in coal. So that’s where the stick comes from. I think it’s a greater level of transparency and disclosure that extends across the entirety of the business, and across the asset managers’ investors portfolios, rather than just focusing on, say, green bonds as a niche product.

AUDIENCE: What role do you think the corporates can play in supporting the cascading effect of sustainable finance, and what role do the banks then play in supporting green financing in the supply chain?

Jayant Parande, Olam: It’s a very important perspective and this is something which has been seen in the industry over a period of time. As you rightly said it’s not very easy to get everyone in the ecosystem exactly on the same page. We started business as a supply-chain manager of agri-commodities going down to the farm gate and buying commodities at the lowest level of aggregation.

Over a period of time we realised that there is a significant value in offering a traceability guarantee to our customers – many of whom are global food companies with household brands – that the commodities we are sourcing from are not from farms which use, for example, forced labour practices which continue to be prevalent at some places in emerging markets where these commodities originate. This continues to be valued by our customers as a bespoke value-addition in our business dealings.

I guess to the extent possible, we do try and see that most players involved in the ecosystem – suppliers, transporters, service-providers are on the same page with us in terms of ESG norms.

Aligning with changing consumer trends, it is becoming absolutely critical for global food companies to make sure that the ingredients they are using in their final products – which are high-value consumer brands – are from sustainable sources, and most of them have targets for that.

So things will definitely change… but you’re right, we need to continue to focus on trying to see what we could do more in improving the ecosystem, aligning people, and creating a positive impact.

Mike Tan, Frasers: From our perspective, we are actually on the receiving end of it, for example, Puma, which is a reputable sportswear company, has certain criteria in terms of who they partner with and the warehouses they would rent and logistics they use. In Australia, because of our ESG rating we are one of the Puma suppliers for warehousing space. Then on buildings like, for example, Frasers Tower in Singapore, we built it to green standards we know that the multinational companies would want to lease because it’s got green features that will attract the tenants.

Our supply chain is not as long as Jayant’s, but downstream if you look at the business, we have a lot of malls. We’re probably the second largest mall owner in Singapore and we have begun to look at food wastage, for example. We have a lot of fast food joints. We have restaurants. We have enormous amount of food that’s thrown away, food that can be reused within a four-hour timeframe.

We have also placed food boxes now in our malls so you can donate your non-perishable food and have it distributed to the needy.

So we’re all working on it, it’s how fast and how far we can move.

AUDIENCE: When you talk of financing initiatives which are promoting water use efficiency, there is a huge social aspect also attached to it. I would like to know whether lenders and investors look at these aspects or is it still limited to the green part?

Jane Yuan Xu, IFC: In terms of water usage, particularly for agriculture, 90% of water is used in irrigation in most of the countries. So if that can be done better, that can save a lot of water for countries with limited water resources. That is what we talk about now on the climate smart agri business. That will go through some of the basic infrastructure to improve the efficiency. Then on marine plastic, particularly in ASEAN countries, this is a big challenge. It’s affecting the tourism business and the fisheries.

For IFC and the overall World Bank Group water and solid waste treatment are among the top priorities that we focus on.

Cedric Rimaud, CBI: I think in South-East Asia the social aspect is very important, like you point out, but climate change is also very impactful on the low income populations. The ones that are going to be affected by rising sea levels are from Bangladesh, from far out islands in the Pacific and populations that will be struggling by themselves to cope with those changes.

Unfortunately we need to change and the governments need to accompany that change and take account of the social impact, that’s very important. I fully agree with what you’re saying but unfortunately, we need that change to happen. We cannot just say “let’s continue to use coal” just because it gives work to coal-workers. It’s not acceptable anymore.

Eric Bramoulle, Amundi: I think for the moment we have to accept the fact that the definition of the social aspect in India may differ from the one in Europe or South America. There is a convergence happening. It will take time. Maybe at the end we will have different taxonomies in different regions, but the problem of water in India will be probably completely different from another part of the world. For investors we try to integrate it, but this is not the easiest part.

Sean Henderson, HSBC: I think it’s a very complex issue because there are so many different aspects to what it means to be sustainable or environmentally friendly. It’s very easy to measure the impact of sectors like renewables as we’ve talked about, but in more complex sectors like industrials, or on more complex issues like water or pollution, it’s a lot more difficult to measure what it means to be sustainable, and may also be impacted by local factors that requires specialist local expertise to assess.

This is why I think it’s really important to have institutions like the CBI, for example, who can bring specialist independent expertise to help investors validate frameworks and improve investors decision making.

The risk is some issuers may say, “Oh well the cost of that disclosure and independent assessment is too high for me, it’s too painful,” but we need to recognise that you need to maintain a certain level of independent verification because otherwise it’s very difficult for a broad range of investors to have confidence that what they’re buying is genuinely having a positive impact. It goes back to Eric’s point which is that people will worry more about the definitions and the taxonomy because what if the bond you thought was green was actually not.

We do need to maintain the confidence of investors in this market, and so initiatives to bring down costs and increase the efficiency of ESG disclosures are immensely important.

IFR ASIA: Ladies and gentlemen, thank you very much for your time.

To see the digital version of this roundtable, please click here

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email gloria.balbastro@refinitiv.com