Seven months on from the start of the coronavirus crisis Down Under, a panel of experts took the opportunity to discuss the unique, immense and ongoing challenges facing Australian authorities.

Reserve Bank of Australia assistant governor Dr Christopher Kent opened the IFR Australia DCM Webcast with a keynote speech in which he outlined how an expansion of the traditional monetary policy toolbox has provided additional liquidity and massively boosted the RBA balance sheet.

“In a world of unconventional policies, assessing the stance of monetary policy is not as straightforward as it once was,” he began.

“It used to be that looking at the Board’s cash rate target and coming to a view on its likely path…provided a reasonable summary of the stance of monetary policy. If the cash rate target was lowered, the traded cash rate would decline to that lower rate and policy had clearly moved to a more expansionary footing.”

Kent explained how the monetary transmission mechanism became more complex after March 19, when the Reserve Bank introduced a new package of policy measures, both conventional and unconventional.

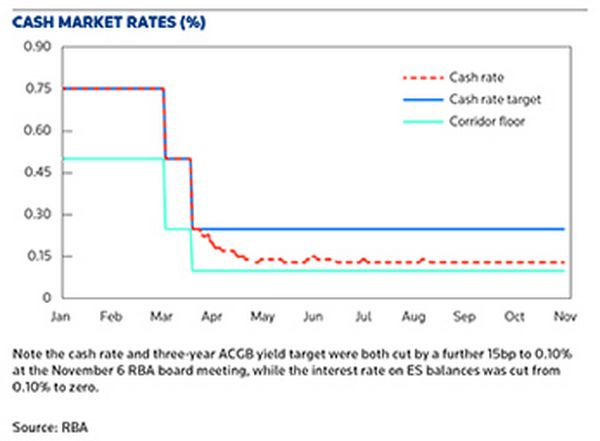

In addition to cutting the cash rate 50bp to a record low 0.25%, the RBA provided forward guidance indicating that the cash rate would not be increased until the board was confident of meeting its employment and inflation objectives.

It also set a target for the three-year Australian Government bond yields of around 0.25%, by purchasing ACGBs in the secondary market, and introduced the Term Funding Facility (TFF) in March to provide A$90bn (US$66bn) of funding to banks for three years at a fixed interest rate of 0.25%.

The TFF was expanded in September to about A$200bn and extended until June 30 2021.

“It’s clear that this package of policy measures represented a significant easing in the stance of monetary policy. The aim has been to lower funding costs across the economy and support the provision of credit, and it has broadly worked as expected,” said Kent.

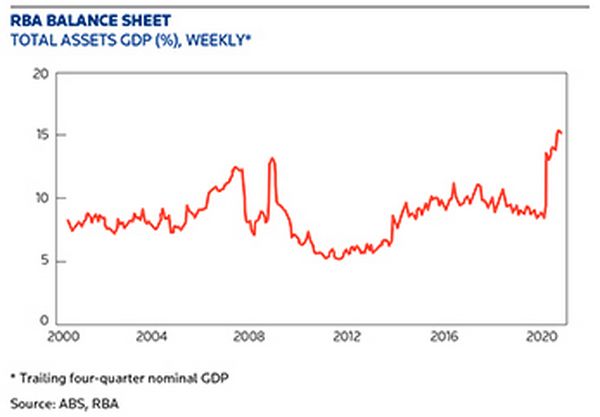

Bond purchases and the TFF provided a further, huge liquidity boost to the banking system as well as a massive expansion in the RBA’s balance sheet.

As a result, the actual cash rate – the rate banks charge to lend out funds to other banks overnight – declined below the cash rate target.

It settled at around 0.13%, which was just above the then 0.10% rate that banks receive on surplus Exchange Settlement (ES) balances in their accounts at the Reserve Bank.

“The decline in the cash rate to be below the target was a natural consequence of the expansion of the Reserve Bank’s balance sheet,” said Kent.

Balance sheet boost

Kent identified three broad options for banks to use money from the TFF; write new loans to households or businesses, purchase securities such as government or corporate bonds, or replace other forms of funding, such as bank bonds.

“In each case, the use of TFF funds results in lower interest rates in the economy. And in the case where the TFF is used to buy a bond or make a loan, it also results in new funding finding its way to a borrower or an investor.

“That is, there is a quantity effect as well as an interest rate effect, whereby an expansion in the Reserve Bank’s balance sheet can lead to additional funding ending up with households, businesses or governments,” he said.

The new tools caused changes in the size, composition and maturity of the central bank balance sheet, which has expanded massively through short-term liquidity boosts, government bond purchases and TFF funding.

“Generally, an increase in balance sheet size under the new policy measures means that the Reserve Bank has acquired an asset from the private sector and in so doing provided some form of monetary stimulus which was also evident during the global financial crisis.”

The current composition of the balance sheet is very different now compared with the GFC, however, as the TFF plays an increasing role and short-term repos are rolled off.

“This change in the composition of the RBA’s balance sheet is clearly evident in the large rise in the average residual maturity of the assets held by the Bank. This is consistent with the need for monetary policy support to be provided for some time given the economic outlook and the prospect of an extended period of high unemployment.”

The main focus of active balance sheet expansion during the global financial crisis was on satisfying the precautionary demand for short-term liquidity, while a deprecation in the Australian dollar also boosted the value of the Bank’s foreign reserve assets.

“Satisfying precautionary demand was also important in the early stages of the pandemic, but subsequently the mix of assets shifted to longer-term repos (via the TFF) as well as government bonds. Consequently, the breadth and the durability of the easing in financial conditions associated with these balance sheet tools has been greater now than was the case during the GFC,” Kent said.

Q&A discussion

The panel gave a general thumbs up to the authorities’ responses to the crisis which enabled Australian financial markets to stabilise after a period of great stress in early March.

“I think the Bank was very transparent and open about their policies and the way they used the TFF to use banks to transmit funding and lower rates through the economy has been very effective,” said Andrew Walsh, head of G10 rates for Australia and New Zealand at Citi.

Fitch sovereign analyst Jeremy Zook believes the RBA and Australia’s fiscal authorities have been quite responsive and effective in their response to the coronavirus shock compared with others around the globe.

“From our point of view yield curve control has certainly been a key factor and we have seen quite a strong fiscal response in Australia that has provided good complementary action to what the RBA has done,” he said.

Soaring supply

Fiscal rectitude has clearly fallen down the list of economic objectives as the government prioritises recovery and job creation.

But with the total government and semi government debt rising by around by 25% in the last 12 months, to just over A$1trn, have there been digestions problems and with plenty more supply to come, do huge fiscal problems lie ahead?

Andrew Kennedy, treasury director at the South Australia Government Financing Authority, noted that when markets were dislocating and liquidity was at a premium in March, there were concerns as spreads blew out, amid anecdotal evidence of offshore divesting alongside domestic fund withdrawals.

“However, the market repriced very, very quickly, primarily due to the fact we did have a strong central bank support in terms of their bond buying targeting and three-year yield target at 25bp. The RBA has also added liquidity through their open market operations and the TFF,” he said.

“So we’ve had central bank support that helped balance out some of the supply issues in the first instance and then we’ve seen strong demand from investors. Australia is still seen as a safe-haven investment with a very stable political environment that offers relatively high rates among the Triple A bloc”.

Looking ahead, Kennedy acknowledges background noise over the deficit and debt problem and the work that needs to be done in terms of heavy lifting by government borrowing agencies, but he also emphasised major offsetting factors in terms of increased investor demand and central bank support for the markets.

Triple A status

Whether Australia retains its coveted position as one of just nine countries rated Triple A by all three agencies is open to debate.

Zook at Fitch, which put Australia on negative outlook in May, said Australia does have fiscal space to respond to the coronavirus shock, but this space has become much more limited.

“From our view there are still a lot of risks and it really becomes important that we see the government’s plans over the medium term and whether the gross debt to GDP level stabilises or goes on a downward trajectory”.

Zook also stressed the importance of whether any downgrade is a one-off or the start of a trend and noted that no sovereign which had lost a Triple A rating with Fitch has ever regained it.

Anthony Robson, CEO of trading platform from Yieldbroker, stressed that the relative benefit of investing in Australia has been significant and the corporate memory of that is very strong.

“We know there’s going to be supply, the question is demand and there aren’t that many choices for high rated debt across the world as far as Triple A and Double A countries are concerned. Personally, I don’t think the impact (of an Australian downgrade) is going to be huge”.

Negative rates

On the prospect of negative interest rates in Australia, Robson does not believe it is necessarily desirable, especially given the impact on retiree returns.

He pointed to enormous social welfare problems in Europe where an ageing population is struggling with negative 10-year sovereign bond yields in four countries.

Though Australia has a positive population growth, particularly in the tax paying bracket, Robson warns that negative interest rates are a dangerous path to go down as it forces retirees to take a lot more risk to generate the sort of returns they expected to get from their nest eggs.

“While it may produce an initial sugar rush, the longer-term impacts are questionable at best.”

Citi’s Walsh concurred as he focused on the impact of negative interest rates in Europe and Japan on the equity prices of bank stocks.

“The institutions that suffer the most out of this have been banks – the hand that feeds the economy – so I think the RBA are very reluctant and have been quite public and vocal about this. Their approach will be a lot more to do with QE and flattening the curve before going down the path of negative rates,” he suggested.

Green sovereign

The success of Australian state government and offshore sovereign green bond issuance raises the question of whether the Australian Commonwealth will dip its toe in the water with an inaugural ESG bond sale.

Chris Dickman, senior portfolio manager at Altius, sees the benefits of such a transaction for both the buyside and sellside.

“We’re very, very keen to invest in more high-quality assets and clearly we’re not on our own so I think the appetite would be quite significant,” he said.

Citing a Canadian study that found around five times more jobs are associated with green energy projects compared to conventional ones, Dickman said: “From a government perspective I would have thought it was a pretty attractive thing to do in an environment when the government is all about jobs, green infrastructure projects have a particular attraction.”

ANZ debt syndicate director Darren Sloane said demand would inevitably be strong for an inaugural federal government green offering, but it was difficult to speculate on whether this is likely to happen because such decisions are issuer-led.

Sloane also noted that while trends, particularly in Europe, have begun driving green or ESG issuance inside benchmark curves, from a domestic investor’s point of view there is a preference to price in line with non-green sovereign lines.

To see the digital version of this roundtable, please click here

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email gloria.balbastro@refinitiv.com