A leading official at Ukraine’s finance ministry has asked bondholders to consider writing off the sovereign’s debt as calls mount for the beleaguered country to consider restructuring options such as a temporary standstill on servicing its bonds.

Ukraine has received pledges of financial support from countries and multilateral agencies such as the World Bank since it was invaded by Russia a month ago. Those donors would be reluctant to see such aid used to service private sector debt rather than helping the country’s defence.

For now, Ukraine has insisted it will continue to service its debt. But Yuriy Butsa, Ukraine's government commissioner for public debt management, said he would be willing to listen to those investors happy to write it off.

He told IFR that Ukraine would consider any "bondholders willing to offer" their notes "for voluntary cancellation".

"Practically speaking, any of the holders can just transfer bonds to our accounts indicating they are donating them for cancellation," he said.

The appeal thrusts the issue of moral hazard to the centre of a debate about whether investors should continue to receive much-needed hard currency from a country that is defending its right to exist.

“It is insane for Ukraine to be borrowing additional funds – including from the official sector but also from the private sector – at a time like this just to pay foreign bondholders,” said Mitu Gulati, a law professor at Virginia University and sovereign debt expert. “They need the money for their defence and to help their suffering people.”

Ukraine had total debts of nearly US$98bn at the end of 2021, according to the finance ministry. Non-government organisations such as Jubilee have called for its debts to be cancelled. Others have suggested a moratorium. Yet bondholders are currently reluctant to consider such scenarios.

One investor said the ethical argument around Ukraine was "challenging". He said that if criticism against bondholders for continuing to receive payments from Ukraine "is the line of attack, then what about those investors that have decided to stay invested in Ukraine, who are long-term investors and who will be there on the other side" of the war.

Another investor said it wasn't possible to just stop accepting payments from Ukraine. "We can't rightfully not accept payment from Ukrainian bonds as this would be lax fiduciary care," he said. He could only do so as a result of a specific client request. "If the client advised us otherwise then we can act upon their requests."

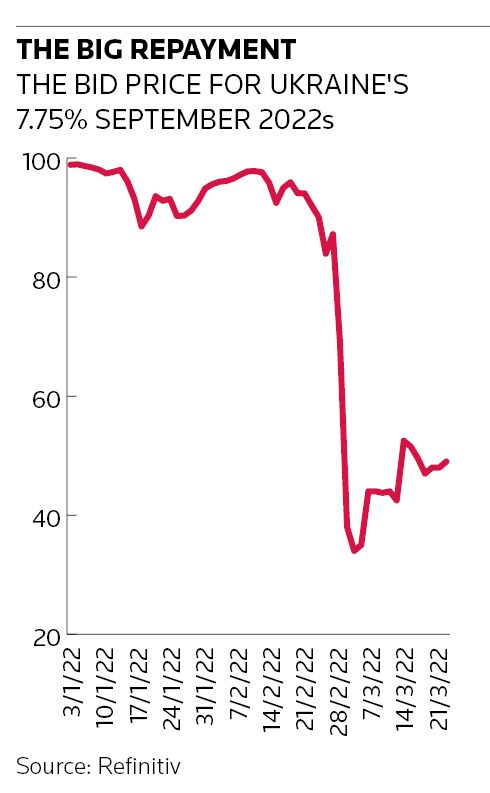

The sovereign made US$292m of coupon payments on March 1 on a series of notes that mature on September 1 each year between 2022 and 2027 in a demonstration of its determination to avoid a restructuring.

"Even in these extreme conditions Ukraine is fully committed to servicing its debt both in local and hard currency," said Butsa. "We don’t plan any debt restructuring. We need to have stable and continuous access to both concessional and commercial financing and any restructuring can severely disrupt it."

War bonds

Luckily, Ukraine has a relatively light debt repayment schedule in 2022 compared to previous years, Butsa said, with external repayments of US$2.27bn due before the end of the year, and much of that concessional. A September 2022 Eurobond is Ukraine's largest single obligation due this year, at US$912m, according to Butsa.

The government has engaged in a series of auctions to raise money through so-called War bonds to fund its military effort and to cover its debt payments. Last week's fundraising of H6.037bn (US$206m) through its fourth auction, edged the total raised across the sales close to the US$900m-equivalent mark. These bonds are being sold at levels well inside where Ukraine was trading before the invasion. Ukraine has stopped foreigners converting hryvnia and some foreign investors are putting the trapped money into the bonds.

Help has also come from the international community with US$1.4bn provided to Ukraine's state budget through the IMF's Rapid Financing Instrument, and discussions are taking place on further cooperation. Whether Ukraine's official creditors would be happy for any money given going eventually into bondholders' pockets is another matter.

“It strikes me as crazy for them to be servicing the debts. They should be able to do a consent solicitation with the collective action clauses in the Ukrainian bonds to ask for additional time to pay the debts – extension of maturities, that is,” said Gulati.

“I suspect that the big holders of the debt will find it hard to vote no against such a request. And that’s the whole point of having CACs – to be able to do something like this.”

Russian clawback?

Moral – as well as specific ESG – considerations are also emerging on Russia's debt repayments. Although Moscow has stopped paying foreign investors on its local currency bonds, it has – to the surprise of many – continued to make payments on its foreign currency bonds, and in their currency of issuance.

"I am surprised they continue to service their debts given that certain parts of the country are now viewed as uninvestible – ie, local markets and the equity market – and investors aren’t likely to want to return to holding Russian assets. So there seems limited upside to remain current on their obligations," said the second investor.

After making US$117m of coupon payments that were due on March 16 on its 2023 and 2043 notes, the sovereign processed another US$66m payment on its 2029s last week. The latter was especially notable because that was one of six bonds that contains fallback language that allows for potential payment in roubles if Russia is unable to use foreign currency for "reasons beyond its control". Another one of those six bonds, the 2035s, has a US$102m coupon payment due on Monday.

Some question, however, whether Russia's foreign creditors should be reaping financial rewards from Russian bond payments, arguing that they should instead redeploy proceeds to Ukraine's reconstruction.

"Maybe bondholders who bet long Russia would now like to donate the coupon payment to the reconstruction of Ukraine," said Tim Ash, EM sovereign debt strategist at BlueBay Asset Management.

Economic historian Adam Tooze has also been critical of bondholders profiting from the war. "If you invest in Russian government debt what are you hoping to profit from? You are investing in Putin’s regime, warts and all," he wrote on March 17.

Even if Russia had defaulted – or does so in the future – Tooze wrote that bondholders shouldn't have priority claims, with the war overturning the sanctity of bond contracts.

"Imagine a situation in which Western interests who have invested in Putin’s regime have priority in claims against Russian assets relative to other potential claimants, for instance Ukrainian victims of Putin’s aggression … It would be a staggeringly perverse situation."

The issue of moral hazard has been brought into special focus on the six bonds that have the rouble fallback language. They were all issued following Russia's annexation of Crimea in 2014 and after various sanctions had already been imposed against certain Russian companies and individuals. The prospectus on those notes even warned of further geopolitical tensions.

Many EM investors acknowledge these concerns and understand the sentiment behind calls for Russian money to be used to help Ukraine.

"I can see broader support to the idea that various private sector claims from the Russian state as well as the frozen Russian assets to be directly linked to supporting the victims or reconstruction efforts, assuming things won’t be resolved," said Kaan Nazli, a portfolio manager at Neuberger Berman.

However, other investors said that would only be possible if their clients allowed them to. One was even more blunt, saying that while there were valid points on both sides of the debate, ultimately "money talks and is the driving force on what we do [or] don’t do in various circumstances".