To assess the chances of a China bond market recovery, IFR brought together a panel of experts in its China Onshore/Offshore Roundtable, sponsored by CICC, Fitch Bohua and Fitch Ratings. It was hosted by IFR Asia’s bond editor, Morgan Davis, who started the discussion by asking the panel to review the market’s performance during 2022.

David Yim: I’d like to be positive, but the markets in October and November were difficult. Issuance levels are lower around the world and China is no different. For the rest of 2022, we’d like to have a final push to get some trades done, but the market is just not very conducive for bond issuers.

Jenny Huang: If we look at the corporate sector from a net issuance perspective, then we’ve had a very weak year this year – mostly dragged down by property developers, which were responsible for around US$40bn in negative net issuance over the first nine months.

For property developers to normalise their funding programmes, it will require national property sales to restabilise and, unfortunately, we haven’t seen any obvious signs of that returning. It is unlikely to do so any time soon, especially as the top policy makers at the National Congress continued to reiterate that houses are for living and not for speculation.

Net issuance from other issuer groups is also lower than last year, largely because of the divergence in costs between onshore and offshore markets. The funding levels between onshore and offshore are likely to be sustained for a while, so we don’t expect issuance to pick up very quickly. Corporate supply will remain under pressure.

Hwang Hwa Sim: I agree with Jenny and David. Issuance is down and the expectation is that volumes will continue to be subdued through to the end of the year. Interest rate concerns and US dollar strength will continue to be a drag on the market.

To put this in context, during the first three quarters of this year we saw about 250 deals completed. Over the same period of last year there were probably more like 440 to 450 deals. Volumes are down by at least 50%. There’s still activity on the local government financing vehicle side, but volumes are lower there as well.

Very importantly, although markets continue to be subdued, there will still be deals, they’ll just be a bit more difficult to do. We just need a slightly calmer market. Hopefully, we can get some deals out before the end of the calendar year, and hopefully next year will be much better.

Daqian Darius Tang: Overseas bond volumes are understandably lower given the US is hiking interest rates and the poor performance of China’s real estate sector. China US dollar bond issuance this year is probably down by as much as 40% to 50% to volumes seen in 2021.

Vienna Lit: As the others suggested, tumbling issuance levels this year are mainly a result of the US rate hikes. It’s true there have been some deals from the LGFV sector but, looking at the rest of the year, then the US rate environment is probably going to limit the supply of bonds from Chinese issuers in the US dollar market.

IFR Asia: Vienna, how does US dollar bond issuance from China compare to other emerging markets. What are some of the specific China dynamics affecting supply?

Vienna Lit: Compared to other emerging markets, Chinese issuance of US dollar bonds is relatively stable because the inflationary environment in China is more stable than in some other emerging markets – or indeed the West.

Ample liquidity onshore also makes the offshore market more attractive for onshore investors and we can see a China bid in the US dollar offshore market for lots of high-quality sectors, such as the financials, the high quality LGFVs and the state-owned enterprises. Those sectors have outperformed some of the other region’s bonds this year.

That’s a positive sign for Chinese issuers.

I’m sure investors are also looking at emerging markets, other than China, especially countries that have performed well in controlling inflation. From this perspective, some of the other Asian economies, such as Malaysia or Indonesia, also provide a good yield.

IFR Asia: David, what has changed in 2022 for Chinese issuers in US dollar bonds?

David Yim: As I mentioned earlier, the volume is down in all sectors; we’ve hardly seen any issuance. I guess we don’t need to explain too much about the real estate sector, and there’s been hardly any deals in the TMT, or tech sector. What’s left is mainly the financial institutions, LGFVs, and SOEs. Even SOE issuance this year has been limited.

High quality, highly rated SOEs are not issuing as much as in previous years. And when it comes to refinancing, they’ve found other funding channels much cheaper than dollar bonds.

Having said that, whenever a high-quality Chinese issuer does a dollar bond, they still get a lot of interest from PRC investors – simply because the liquidity is onshore. Some of these PRC investors, particularly banks, are still looking for yield pick-up from some of the PRC names that they know, that they’re comfortable with. They are still looking to put their money to work.

International investors may think differently, of course, because in the EM world or the DM world, there are plenty of attractive alternative assets they can get for yields similar to those Chinese issuers are prepared to pay.

What makes 2022 hugely different from previous years is that demand for China offshore issuance this year is dominated by PRC investors. That’s not because international investors have any major concerns over Chinese issuers other than certain sectors like real estate, it’s just that the international investor, which has more choice, finds China dollar bond yields less attractive. They can find other, more attractive assets in other countries.

For example, issuance from Korea is higher this year than last. We also see a lot of Chinese investors buying Korean paper. That is something we’ve not seen so much of in the past. In previous years, there was so much supply from PRC issuers that PRC investors simply had no need to look elsewhere to complete their investment programmes. This year, given the shortage of China supply and given the attractive yields offered by Korean issuers, Chinese investors have shown more interest in Korean paper.

IFR Asia: What currencies are looking most attractive for Chinese issuers? Where do they go if US dollar bonds are off the menu?

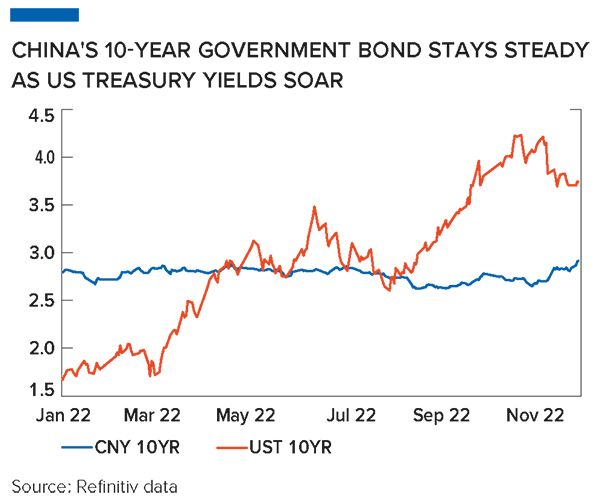

David Yim: The onshore/offshore pricing differential is making it difficult for PRC issuers to do a dollar bond. There’s easily a differential in cost of, say 2% or 3%, compared to issuing bonds onshore in renminbi versus dollar bonds.

This is very different from the beginning of 2022, when two-year US Treasuries were trading at less than 1%. Now we’re talking about 4.5%. Rate hikes during the year have made it very unattractive for PRC issuers to borrow in dollars, especially when they have other funding alternatives. Dollar bonds are probably the least preferred option for them.

Dollar bonds are only for those issuers that still have some dollar funding needs offshore, and for which other funding channels may not be available or efficient. Some of these Chinese issuers have chosen to issue Dim Sum bonds in Hong Kong instead, for instance.

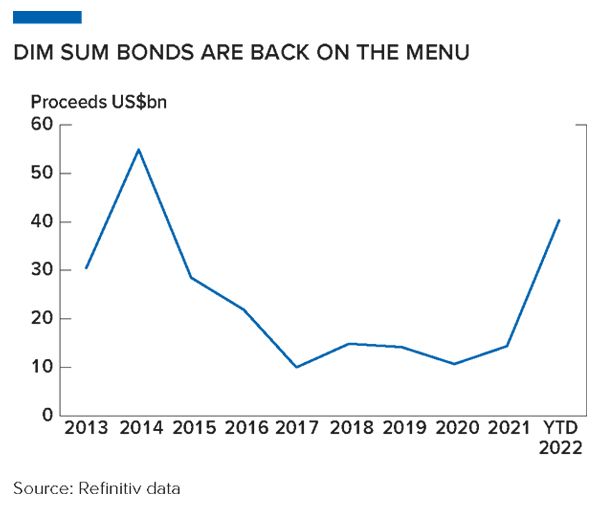

We have seen a lot of offshore renminbi (CNH) issuance compared to last year – issuer volume is about 200% higher, year on year. This is partly because of the liquidity situation at home especially via the Southbound Bond Connect channel which has seen investors from China looking for yield pick-up in the offshore market.

IFR Asia: Jenny, could you tell us a little bit about the LGFVs we are seeing in the dollar market, or the Dim Sum market, or even euros recently. What characterises the types of LGFVs that are coming offshore and what do these transactions look like?

Jenny Huang: Lower issuance in the LGFV space is due to fewer deals from some of the wealthy regions. We think this is partly due to the high levels of supply last year, but also because of the funding differential.

We have also seen more issuance using a standby letter of credit (LC) structure. This is something more normal for lower quality issuers, and it suggests that investors are concerned about some low-quality issuers. Investors are demanding more credit enhancement to get the deal done.

IFR Asia: Can you tell us what you mean by credit enhancement?

Jenny Huang: I was mainly referring to standby LCs. This type of structure has given confidence to investors with some successful cases of repayment by banks, and lower quality issuers are now taking this route. It reduces funding costs and helps deals get through.

Banks offering this kind of product usually have other relationships with these issuers so there’s an incentive to provide such a service, as they can earn fees from ancillary business.

David Yim: If I can chip in? This year, we’ve seen a lot more LGFV issuers – a lot of new names in the market. These are less recognised in the offshore market and maybe are weaker credits. That’s why they need some sort of credit enhancement to get their deals done.

The point that I want to make is that sometimes it’s difficult for international investors to look at this type of asset or product, simply because – in most cases – the standby LC provider, as well as the issuers, are not rated. It’s difficult to do credit analysis on the standby provider and the issuer, so they decide not to invest.

That explains why these deals tend to be smaller in size, maybe of US$50m–$100m. They are new players in the offshore market, they have approval from the National Development and Reform Commission, and they use their quota to issue in the offshore market. Although the deal sizes are not that big, there are several of them and that is supporting issue volume from China. Without those smaller LGFV borrowers, issue volume would be down even more.

IFR Asia: Do you see these standby LCs, the keepwells, and guarantees helping sell the transaction, or helping with the price?

How much comfort do they afford investors? I mean, we’ve already seen court cases with keepwells, and questions around whether they’re going to hold up. How much faith is there in these credit enhancements?

David Yim: Investors in regional SOEs or LGFVs are mainly Chinese banks or security houses, so they do understand these credits. And because of the deal size, and because of the number of investors in these types of deals, they are almost like club loans.

When investors buy these deals, they must be comfortable with the credit enhancement and the issuer. Most likely the bonds would be held till maturity. These products do not appeal to international investors.

It’s like an onshore deal but conducted in the offshore market.

IFR Asia: Vienna, could you tell us how you’re seeing these credit enhancements used?

Vienna Lit: From the issuer’s side, it’s a benefit for some as it lowers the cost of borrowing, because the rating is linked to the underwriting bank. Most of the banks have investment grade ratings.

I know there are a lot of concerns about standby LCs but in the longer-term I think investor recognition will improve, and this will help issuers save on costs.

This development will continue, and I think other market investors will slowly gain confidence in standby LCs.

IFR Asia: Another thing I want to touch on is the implicit government support for some of these Chinese issuers. That’s something that the market has expected for SOEs, and maybe for some of these LGFVs, depending on the tier of the city.

Darius, could you tell us a little bit about government support for issuers? Is it something we can still count on?

Daqian Darius Tang: According to the laws and regulations in China, Chinese local government debt and debt from SOEs are completely separated. The local government is prohibited from providing any kind of guarantees to SOEs or even making any direct debt payments on their behalf.

However, as analysts we think that implicit support, either from local government or the central government, has an important impact on the credit quality of SOEs, including the platform companies, the LGFVs.

For platform companies that are engaged in large-scale not-for-profit businesses that do not create cashflows themselves, their cashflow is highly reliant on returns of land sales from upper government, or financial subsidies.

Evaluating the impact of government support on SOEs or platform companies has two aspects. One is the support capability and the second is the willingness to use it. This comes as a consequence of the macroeconomic downturn.

Tax revenues, an important source of revenue for local governments, are under tremendous pressure. And due to the downturn in the real estate market, land is much harder to sell. This also has a strong negative effect on revenues.

From the expenditure side, although some expenditure can be reduced, others cannot – such as for Covid-19 control or government debt repayments.

If a local government fails to make a bond payment, then the whole regional financing environment will face systematic deterioration. This is something that a local government would be very reluctant to see, especially when the economy is already in a downturn.

I think that with the economic downturn, the government’s ability to support SOEs and platform companies has deteriorated. But for some companies the willingness remains.

An SOE default would have serious social and political implications for the government and the regional financing environment would deteriorate dramatically.

In this case, SOEs would get priority. Local government would have an incentive to support utility companies, companies providing public services, or some common entities.

IFR Asia: Jenny, could you add anything as far as government support is concerned, maybe in the wake of the Party Congress meeting. What should we expect in terms of government support?

Jenny Huang: Firstly, I totally agree with Darius. The answer really depends on how strategically and systemically important an entity is to their stepparents.

Tolerance levels on defaults have been increasing. Since the first default in 2014, we have seen defaults spreading from privately-owned enterprises to SOEs – the relatively unimportant SOEs to begin with and then to some large local SOEs. It's part of the government’s plan to enable a more efficient flow of capital and to control total leverage in the system.

Will default risk spread to other groups of issuers? The answer is yes, but the process is likely to be gradual. As Darius just mentioned, systemic risk is the last thing the government wants to see during economic downturns.

The Yongcheng Coal default shocked investors and the market, and it led to a large-scale sell-off of SOE bonds and other government related entities with similar attributes. If we can take anything away from this case, it’s that the government is more likely to manage such high-profile defaults in an orderly manner.

If the government decides to withdraw support for a certain group of issuers, particularly those that the market currently views as strategically or systemically important, then we are likely to see some expectation management at work to reduce the shock to the market and limit the systemic risk.

IFR Asia: One of the ways we see the government interact with the market is through the regulators, like NDRC, to which these issuers must apply to issue in the offshore bond market. We’re always hearing about changes in attitude and possible policy shifts when it comes to the NDRC.

While we don’t have anything official at the moment, we know that the NDRC has been speaking with the market and reviewing its policies for offshore issuing.

Hwang Hwa, could you tell us a little bit about the role of the NDRC and the possibility of changes soon?

Hwang Hwa Sim: From a legal and regulatory perspective, one of the ways to look at the NDRC is as the regulator of how much debt Chinese companies can take on.

Its role is to make sure that there is an efficient and well-regulated market, so it is constantly talking to market participants to gain views on the external environment and an understanding of the risks in the market.

We don’t see any potential significant regulatory changes ahead. Obviously, the NDRC will take the pulse of the market and be aware that right now, in this market environment, there are more risks than there were two or three years ago, for example.

It will be making sure that the PRC companies that come to market will have the ability to repay investors, and hopefully will be doing a deal that is of a size and of a tenor that is suitable.

IFR Asia: David. How does this affect the issuers you’re working with and how can you prepare for changes at the NDRC?

David Yim: We have seen this for many years. In 2015, the NDRC first started asking issuers to submit material before they can give a quota in circular 2044. In subsequent years, there have also been updates and clarifications to ensure issuers understand what they’re referring to.

For example, a few years ago there were some updates on property companies, on LGFVs, that, in short, their quota would only be granted for refinancing of debt maturing within the 12 months. These are all measures to contain the amount of debt.

Of course, only the regulator would know which companies are considered to be LGFVs, and that’s why you see new companies issuing foreign debt.

The process is in place. To start with, it was supposed to be for registration only, but everybody knows it’s about seeking approval. If you’re not granted approval or quota, you simply cannot issue offshore debt.

There’s always some confusion as to who needs to apply and how long approval will it take. The process varies. It ultimately depends on how keen the regulators are in seeing more offshore debt. If they feel there’s too much foreign debt, they may slow down the process. That’s why it’s never a set timeline. You submit everything and then in two months’ time, or two weeks’ time, then you’re given a quota. It’s like a black box.

As long as the application is legitimate, it becomes just a process.

Coming to this latest development, there was a consultation paper circulated to all counsels and banks asking for comments on how the process should be reviewed and updated.

There’s talk of potential changes to tighten the process up. Maybe because over the last 18 months or so we have seen an increase in defaults from Chinese companies in the offshore markets. It’s always good to check again to make sure the systems and processes are in place.

Hopefully, any changes will not be too stringent or too difficult for issuers or participants. We want an open market. Chinese issuance in the offshore market has grown so much in the past five years, that we definitely do not want to see a backward-looking approach and a reduction in activity.

That’s especially important in a year where the market is already disrupted and we’re seeing half of the issuer volume compared to last year. The last thing we want to see is more stringent rules and further reductions in issuer volumes.

IFR Asia: David, is there an average timeframe to get any sort of registration?

David Yim: It could be weeks; it could be a few months. It depends on what time of the year and which year. As I said, there must be certain objectives from the state on how much foreign debt is permitted, but that may be different by region or sector.

We’ve come across cases where a property company or financial institution has been waiting for a quota for over a year.

There’s no particular reason. Issuers have had to update their financials two or three times in the interim because they’ve been waiting so long for approval. On the other hand, I’ve heard issuers receive approval in two or three weeks. Very smooth, no questions asked.

I don’t think there’s one answer as to how fast it is to get all the approvals processed.

IFR Asia: Let’s talk about internationalisation of the renminbi. Hwang Hwa, could you tell us about the progress we’ve seen on this front during the last year?

Hwang Hwa Sim: I’ll answer this question from two perspectives. The first one is from a pure capital markets perspective, and the second is from a perspective that is broader than just the capital markets.

Firstly, from a pure capital markets perspective. Amidst all these dislocated and difficult markets, it is important for us to remember that the internationalisation of the renminbi, together with the integration of the onshore capital markets with the offshore markets, has been significant.

As you mentioned, internationalisation has been going on for a while and at a remarkable pace – through Stock Connect, Bond Connect and even nowadays through things like ETF Connect. I don’t think the pace of change will slow down. Just let me illustrate this by a couple of numbers.

Partly because of Stock Connect, overseas investors, as at the end of 2021, would have held about Rmb3.5trn-worth (US$489bn) of equities assets. And that’s effectively five or six times more than offshore investors held before the start of Stock Connect. Similarly, non-PRC investors would have held, as of the end of 2021, about Rmb4trn of bond assets. Again, that’s three or four times the amount that non-PRC investors would have held before the introduction of Bond Connect.

We’ve come a long way in a short time, partly due to Bond Connect and Stock Connect facilitating flows between onshore and offshore markets.

From a wider perspective, the introduction of the Belt and Road Initiative is important, because it has increased trade flows between participating countries. That has also increased the use of renminbi as a currency in terms of trade, between those countries.

IFR Asia: Let’s talk about the Bond Connect. What is the potential for Southbound Bond Connect and what’s driving interest?

Hwang Hwa Sim: Firstly, we have the US Fed to thank. While the rest of the world is increasing interest rates, the People’s Bank of China is at a point in the rate cycle where it is, if not cutting interest rates, then at least holding them steady.

For an investor sitting in China, the offshore interest rates being offered are going to be more attractive than at home. Because of that there will be a lot of Southbound traffic, and that traffic will continue to flow for as long as the rates differential exists. And it doesn’t feel like the differential will go away any time soon.

The second reason is that there are now more products in which to invest through the Southbound Bond Connect – it’s not just plain vanilla bonds, but also credit-linked notes and inflation-linked notes, for example.

These are the main reasons driving interest in Southbound Bond Connect, and neither of those dynamics are likely to disappear any time soon.

Vienna Lit: I agree with Hwang Hwa. Cross-border access has picked up a lot, as has the broader importance of renminbi capital markets.

In May 2022, in the first review of the SDR Valuation Basket since the renminbi was included in the basket in 2016, the International Monetary Fund raised the Chinese yuan’s weighting from around 11% to over 12%. It’s recognition from the IMF of Chinese efforts to open the financial market.

We have also seen data that shows nearly half of all cross-border transactions conducted by other Chinese financial institutions, enterprises or individuals, is now settled in renminbi. And central bank data of cross-border renminbi receipts and payments in the banking sector is up over 15% year on year.

All the data points to steady progress in the internationalisation of the renminbi. We also believe that global demand for diversification will drive increased interest in renminbi assets. The long-term trend is established and it’s not going to change.

Adding to Hwang Hwa, in addition to Southbound traffic, we also see greater demand for Northbound access, such as with Bond Connect.

IFR Asia: David, what do you see as the future for Dim Sum and Panda bond issuance?

David Yim: Just to finish with renminbi internationalisation: there has been a lot of development in the past few years and the funding or investment channels are now connected so that a Chinese issuer can issue in the onshore or offshore market and an offshore investor wanting Chinese company assets can buy offshore renminbi bonds, or onshore renminbi bonds.

Channels, such as the Southbound and Northbound Bond Connect have made offshore and onshore markets interconnected, but whether we’ll see a lot more issuance is another matter. There are other considerations, and that’s why we’re still not seeing a lot of activities, for example, in Panda issuance.

Panda bond volumes – bonds issued by a foreign company in the onshore market – are about the same this year as last year.

The big change this year is Dim Sum. This year’s issuer volumes in Dim Sum are more than two times that of last year – partly because of this Southbound liquidity. Interestingly, we’re getting a lot of queries from non-Chinese issuers looking to tap into the Dim Sum bond markets thinking about the Southbound liquidity. If there’s so much onshore money looking for offshore assets, why can’t non-Chinese issuers take advantage of it? I don’t think their chances are particularly good.

Certain domestic investors had not been very active buyers of offshore paper – in either dollars or renminbi. But now that a channel has been established to make it easier for them to buy offshore assets, they are becoming bigger players.

Unfortunately, they are mainly interested in the Dim Sums issued by Chinese issuers only, particularly FI names. I don’t see this liquidity helping to increase, for example, Dim Sum issuance by a non-Chinese issuer. Chinese investors are not familiar with non-Chinese names, and they probably would not have credit limits for buying non-Chinese names in any case. This additional liquidity is focused on Chinese names and other non-Chinese issuers are not going to benefit from it.

IFR Asia: Darius, how have China’s net zero ambitions affected the energy sector, specifically when it comes to bond issuance?

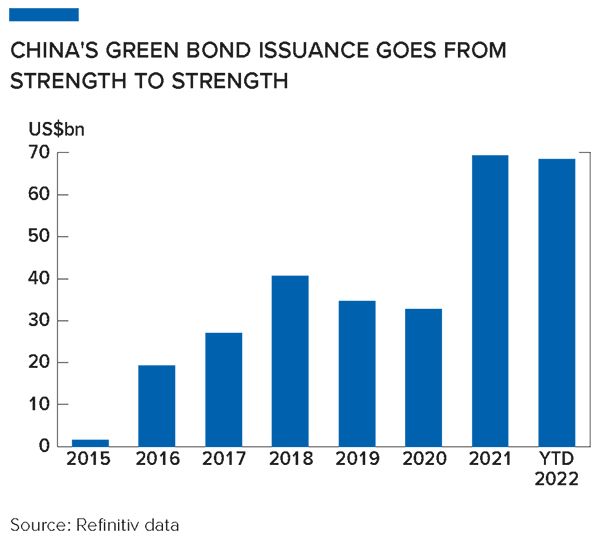

Daqian Darius Tang: The Chinese government has promised to reach its carbon peak in 2030, and net zero by 2060. This means there will be a substantial change in China’s energy structure – if the energy structure does not change, then there is no way to reduce carbon emissions further downstream.

China will now establish a new power system, based on renewable energy as the main source – including wind and solar. We expect the total installed capacity of wind and solar together will reach more than 1.2bn kilowatts by 2030, and we also predict that China’s green power capacity will grow by not less than 700m kilowatts per year over the next five years.

This will need huge investment from the energy companies in China. They will be big issuers in the bond markets. The five major power groups in China, may each need to invest something like Rmb400bn–Rmb700bn in green energy over the next five years to help China’s power industry transform.

This may come at the expense of the progress they have made in lowering leverage in recent years but, nevertheless, we don’t see much downside risk to their credit quality given their sufficient projects experience, diversified power structure and sound financing environment.

To help finance carbon neutrality, we have green bonds. Green bonds are a hot topic right now, but the concept has actually been around in China since 2016. China is one of the largest green bond issuers in the world and utility companies are very active participants.

China’s carbon neutrality ambitions will boost bond issuance from power generation companies and clean energy companies, no matter if it is in the offshore or onshore markets. This is a huge opportunity for them.

IFR Asia: There have been quite a few private credit funds set up in Asia this year. Are more Chinese issuers tapping the private debt space, and, if so, what type of companies are they? What are the advantages and challenges of private debt?’

David Yim: Given the market as it is and rates where they are, for those that are strong credits and have multiple funding channels available to them they will not be looking at this – we struggle to get them to issue any sort of dollar bond in the offshore markets.

For more challenging credits, they will do whatever they can to get some funding, because they have limited financing options. Perhaps this is something that they can consider.

Typically, these credit funds may be looking at something more structured, perhaps something secured by physical assets or shares. Structures may involve the onshore and offshore entities.

To answer your question, I don’t see a lot of these deals happening.

IFR Asia: Is the Bond Connect considered to be meeting market expectations?

David Yim: Over the last few years, we’ve seen a lot of interest from international investors buying bonds issued by Chinese companies via Bond Connect Northbound. Southbound may be a more recent development but it is already fully functioning and we’re seeing a lot of activity from Southbound investors buying into the offshore market.

The primary market has still not got the green light, so when we refer to Southbound liquidity, we are talking about investors buying bonds in the secondary market, or maybe one or two days after the primary deal is issued. As and when we see deals in primary are also permitted, then I think we’ll see more interest from investors.

Just one thing to note, a lot of very active Chinese investors have been buying offshore assets for many, many years, without using this Southbound channel. They’ve been using other channels.

Southbound is set up for those less active investors who do not have access to those other channels.

Whether this is meeting the market’s expectations, I don’t know, because it’s still very much PRC investors buying PRC assets using the Southbound Bond Connect channel.

IFR Asia: Is there an end to the property crisis in sight and are we going to see high-yield issuance return?

David Yim: I’d like to see this sector coming back. For many years this has been one of the most important sectors, the most-followed sector from China, for fund managers, hedge funds, banks and private bank customers.

At this point of time, however, the sector is broken. There are a lot of defaults and we’re still not anywhere near the end of the problem. I cannot see this sector returning for the next one to two years, or maybe longer.

A lot of investors got burnt and it’s going to take some time to recover. Even when it does recover, there will not be so many issuers. The days of seeing five issuers on the same day, from the same sector are gone.

In a volatile market, even though you’re not in the property sector, the high-yield market is still not getting attention as yields from other assets are already high.

Vienna Lit: To restore investor confidence will take time. There are signs that it is returning, however.

There are policies to encourage onshore companies, including high yield borrowers, to issue overseas.

Real estate market factors must improve, and we see supportive policies from the government. We see an improvement in real estate sales, but we need to see whether that is sustainable.

Daqian Darius Tang: The Chinese government is doing something to help the real estate market, such as a reduction of loan rates, tax rebates, special loans to guarantee the delivery of buildings, and trying to support Chinese home builders’ financing needs.

The impact of these policies was reflected in September. Sales are still decreasing but the rate of decline has diminished.

China’s real estate market is at a turning point. A revived real estate sector should be accompanied by a rise in household incomes, stable employment expectations, as well as higher house prices. Everyone is just waiting and watching if house prices are going up or down. Only when house sales rebound can we say the real estate crisis is resolved.

It will take time and Chinese property developers may continue to suffer for a while from the lower risk appetite of investors.

Jenny Huang: This downturn is likely to be bumpier than in prior rounds, meaning it will take more time for the sector to recover. Having said that, we don’t expect too much downside from current levels.

Investment bankers have been trying to fill the high-yield issuance gap by broadening the range of names, but with limited results.

Hwang Hwa Sim: The market potential for high-yield issuance hasn’t changed but risk appetite has.

If and when the market comes back and the real estate sector recovers then one thing to be aware of is that high yield as a product itself isn’t the only option. A lot of companies can rely on the equity market. Many of them will be able to do securitisation deals, and some listed companies can do products like convertible bonds or exchangeable bonds.

There will always be a financing option, not just high yield. If risk appetite returns, yield expectations stabilise, and the market resets itself then we will see the next cycle beginning. That cycle doesn’t have to be high yield, there are many other options available.

The webcast is free to view, on-demand. Access it here.

To see the digital version of this roundtable, please click here

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email gloria.balbastro@lseg.com