A year in the life of bond banker reginald sellars

![]()

To see the digital version of this report, please click here

To purchase printed copies or a PDF, please email shahid.hamid@lseg.com

There are new features available.

View now.

Search

There are new features available.

View now.

Search

![]()

To see the digital version of this report, please click here

To purchase printed copies or a PDF, please email shahid.hamid@lseg.com

Financiers led by HSBC chief executive Noel Quinn put on a united front in November when Hong Kong hosted the Global Financial Leaders Summit. Timed to coincide with the resumption of the Hong Kong Sevens rugby tournament after a two-year coronavirus-induced hiatus, the conference was designed to herald a return to business as usual. “We have to help Hong Kong through this next phase of post-pandemic restrictions and continued economic growth to strengthen the confidence of Hong Kong as an international financial centre,” Quinn told the...

In anticipation of its centenary, the government of Indonesia in 2019 unveiled “The Vision of Indonesia 2045” which set goals to become an advanced, prosperous and fair country by that date, along the lines laid out in the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. While the aim of becoming a fully developed nation by 2045 might look to cynics as an example of time-washing, the vision exemplifies the grand legacy ambitions long harboured by President Joko Widodo. The president, known by his nickname of Jokowi, has been in office for over...

Japan made waves in the green finance world with its announcement in May 2022 that it would issue ¥20trn (US$157bn) of bond instruments to finance its transition efforts. There was just a little hiccup with the yet-to-be-ratified grand plan: the financing instrument of choice is transition bonds. This is a vaguely defined category of fixed-income instruments to help, as the name implies, companies move to renewable energy sources. This softly-softly approach is perhaps not surprising, given that coal and natural gas still make up 68% of...

To see the digital version of this report, please click here To purchase printed copies or a PDF, please email shahid.hamid@lseg.com

To see the digital version of this report, please click here To purchase printed copies or a PDF, please email shahid.hamid@lseg.com

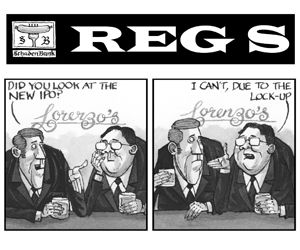

Bond portals Where Indian retail investors do their online shopping. Buy now pay later A new way to lend to people who can’t afford to repay. Cryptocurrency A decentralised asset that does away with everything that holds back the conventional financial system, like rules and accountability. Dim Sum Survival fare for fee-deprived Hong Kong syndicate banks. Double label 1 ) Debt transaction encompassing more than one kind of ESG financing; 2) Banker put in charge of ESG financing on top of their main job. Due diligence Elon, it’s a bit late to...

All websites use cookies to improve your online experience. They were placed on your computer when you launched this website. You can change your cookie settings through your browser.