Non-bank trading firms are generating less than half their revenues on average from market-making activities comparable to those at large investment banks, new analysis shows, underlining how risk-taking and proprietary trading have been instrumental in the dizzying growth at companies such as Jane Street in recent years.

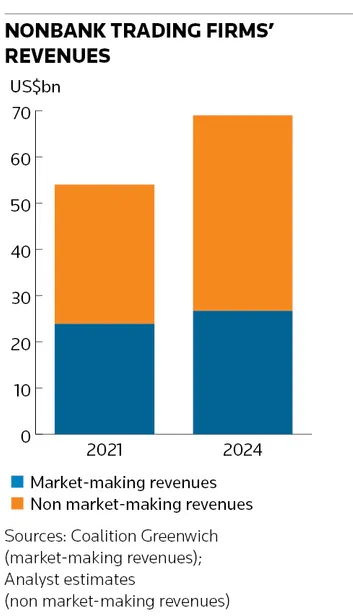

So-called non-bank liquidity providers raked in US$26.7bn in market-making revenues in 2024, according to data provider Coalition Greenwich, a 12% rise from three years earlier – and broadly in line with the pace of growth in banks’ trading operations.

These trading firms have grown overall revenues by nearly 30% during that period to a record haul of around US$70bn, analysts estimate from firm disclosures, suggesting that proprietary trading has accounted for the bulk of that increase across the industry.

The Coalition Greenwich research sheds some light on the secretive business models of such firms, whose breakneck expansion has unsettled traditional investment banks. Banks have become increasingly worried that these smaller, tech-savvy rivals could prise away the core client business that has become the epicentre of banks’ trading units over the past decade and a half as they have dialled down their own risk-taking.

But the research suggests trading firms aren't making inroads into banks' institutional client business as rapidly as previously thought, while also highlighting the crucial role that risk-taking and proprietary trading – areas where traditional banks face regulatory barriers – have played in their rise.

“On average, less than 50% of [non-bank liquidity providers’] revenues come from market-making activities comparable to [those at] banks,” said Raman Kalra, head of NBLP competitor analytics at Coalition Greenwich. “On a comparable basis, we see market-making for NBLPs has grown more in line with bank performance over the same period.”

Risk-taking

Many trading firms aren’t publicly listed so there is limited information about their operating models, but industry insiders note that their approaches vary considerably. Many embrace the “proprietary trading firm” moniker and don’t hide the fact that they generate a significant chunk of their revenues from pure risk-taking.

Others – such as Citadel Securities, the market-making firm majority-owned by hedge fund billionaire Ken Griffin – emphasise their role as liquidity providers and have outlined plans to increase their market-making presence buying and selling securities on behalf of institutional clients.

Either way, the eye-popping revenue numbers emerging from these firms have certainly made banks sit up and take note. Goldman Sachs, long considered a poster child for trading prowess, grew its markets revenues by 13% last year to US$26.6bn. Analysts estimate from firm disclosures that Jane Street, by comparison, roughly doubled its overall revenues to about US$20bn, while Citadel Securities' grew by 60% to about US$10bn.

Those headline figures only tell part of the story, though, and almost certainly overstate how much client-related business trading firms are capturing. Jane Street, the largest of these upstarts, typically generates close to 70% of its revenues from proprietary risk-taking, according to sources familiar with the matter.

XTX Markets – which has become a major player in foreign exchange and European equities – also makes the vast majority of its revenues through prop, sources said. Citadel Securities, by contrast, generates the vast majority of its revenues from client-related activity, according to sources.

Spokespeople for all three firms declined to comment.

“The question is: what is their relationship with the end clients?” said a senior trading executive at a major bank. “Is it a client broker-dealer relationship where the job is service, or is it a prop and principal relationship where the goal is monetisation? Their numbers point to it being very profitable whatever they're doing.”

Stealing a march

Trading firms have long dominated the multi-billion-dollar business of trading US stocks after they stole a march on traditional investment banks following the rapid electronification of these markets over the past two decades. More recently, they have been threatening to break the stranglehold banks maintain over other markets such as trading bonds and currencies.

Jane Street has leveraged its dominant position in exchange-traded funds to become one of the biggest traders in corporate bonds almost overnight as the electronification of these markets has accelerated. Citadel Securities, meanwhile, has targeted senior bank traders in a recent hiring spree as it also looks to expand in corporate credit.

“Trading firms, along with banks and other market participants, create a robust and diversified market that facilitates reliable liquidity across asset classes and around the globe,” an official at FIA Principal Traders Group, an industry body representing trading firms, told IFR.

A senior executive at a trading firm put it more bluntly, saying: “It was never preordained that banks should be the main or only intermediaries in capital markets.”

Making headway

Trading firms now account for more than 10% of total industry revenues in flow credit trading, according to Coalition Greenwich. They have also gained ground in digital assets – a more lightly regulated corner of markets where banks are treading more carefully – and equities trading, making up around a third of the market in cash equities and ETFs. Analysts said the particularly strong year for stock traders in 2024 undoubtedly helped firms such as Citadel Securities, which says it handles nearly a quarter of all US equity market volume.

Coalition Greenwich says banks’ total industry trading revenues still increased by 11% over the past three years to just under US$230bn – over eight times more than non-banks made from market making last year. However, the main drivers of this growth came from businesses in which trading firms aren't active.

Chief among these were financing activities such as prime brokerage that reside in banks' trading divisions, where they lend money to hedge funds and other institutions (including trading firms). That implies trading firms took more share than the headline Coalition Greenwich numbers suggest in market making of simpler, "flow" products that trade on exchanges and other open venues where they compete with banks.

“While growth rates for banks and NBLP market-making activities are similar, financing has been the outperformer for banks across both equities and fixed income,” said Kalra.

Clients and competitors

David Solomon, Goldman's chief executive, said last year that the scale, global reach and finance capabilities of banks such as Goldman should put them in good stead with clients amid the competition from trading firms, while also highlighting "certain regulatory arbitrages" that the likes of Jane Street and Citadel Securities enjoy.

Most trading firms are regulated as broker-dealers in the US, but they aren’t subject to the various regulations devised in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis aimed at limiting risk-taking in banks. Those include having to set aside capital against trading exposures and the US Volcker rule banning proprietary trading on most securities.

Having greater leeway to place wagers on financial market moves may confer some advantages beyond making outsized profits. It can, for example, allow firms to build a presence in an asset class without having to engage in the laborious and often costly process of building a client base first. The flipside is that it may make it harder to court those same clients if they’re worried about getting ripped off.

“Clients are very concerned about information being used in any way, shape or form that's adverse to their own interests,” said the nonbank trading executive. “And clients vote with their feet. If they don't trust you, they don't trade with you.”

The potentially more mercenary approach of some trading firms is certainly something that bankers remind their clients of regularly. Some are taking other measures to slow down the advance of nonbanks where possible.

“We watched what happened in equities and we thought about how we deal with [trading firms like] Jane Street differently,” said a senior fixed income trader at a major bank. “I don't think you will find that they become a huge financing client for credit like they are in equities. We’ll deal with them when we need to, but I don’t think we have any interest in letting them in like we did in equities.”