The Australian green bond market has walked a narrowing path in recent years with overall supply, though relatively steady, now dominated by fewer but larger benchmark deals from state governments and SSA issuers.

Beyond these two buoyant segments, corporate and bank ESG issuance has contracted markedly, a reflection of evolving issuer and investor priorities.

This recalibration was underscored by Port of Newcastle’s A$300m (US$196m) eight-year domestic debut on July 10, a result the world’s largest coal export terminal could only have dreamed of when enthusiasm for ESG was at its peak.

“ESG momentum has faded over the last few years after reaching a zenith around 2021 when PON sold its Yankee bond, a time when doing such a deal locally was unimaginable,” said Brad Scott, head of DCM at Bank of China in Sydney.

“The mojo for green and sustainability-linked bonds fell away amid taxonomy changes and greenwashing concerns. Corporate issuers are now focused on AI, cybersecurity and the fallout from geopolitics, often baulking at the extra time, money and effort required [to sell green bonds], especially as potential greenium savings are debatable.”

Turning to the buyside, Scott said fixed income investors have become indifferent to ESG labels with the predominance of flexible light green mandates meaning funds have scope to focus on the credit and the return on offer.

“The corporate story this year is about yield, especially in the booming hybrid space, with 6%-plus returns persuading many investors to come out of the woods.”

Scott said this was the case for PON, which attracted a A$3.2bn order book, though that was inflated by around A$1bn as order sizes were scaled up after the deal was capped at A$300m.

Even taking out the elevated final book, PON’s domestic debut was seven times covered, double the average cover for corporate sales this year, including hybrids.

Pauline Chrystal, portfolio and ESG manager at investment manager Kapstream Capital, which focuses on transition stories rather than labels, said the incentive for corporates to issue ESG bonds has declined.

“Green bonds used to offer greater execution certainty thanks to the heavy oversubscriptions they drew. However, the overall growth in demand for Australian dollar corporates means vanilla bonds now deliver the same execution benefits without incurring the additional costs and reporting burden associated with green programmes.”

Late starter

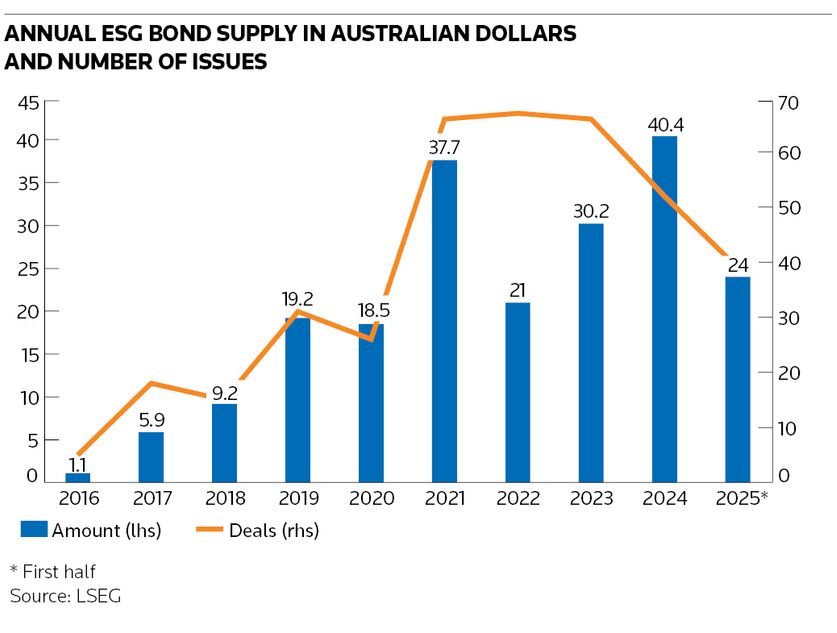

Australia was a late starter in ESG but issuance picked up rapidly from just A$1.1bn in 2016 to A$37.7bn in 2021 before dipping to A$21.1bn the following year, according to LSEG data.

A record A$40.4bn was achieved in 2024, buttressed by the Commonwealth government’s A$7bn green debut, but the number of issues was the smallest since 2020 with 52 bonds printed versus 66 or 67 in the preceding three years.

Almost A$24bn has been raised in 2025 from 39 issues, dominated by SSAs and Australian states.

“The Commonwealth debut provided a big boost to the market, while semi-governments have stepped up their ESG programmes with Western Australia and South Australia joining the club in 2023 and 2024,” said a sustainable finance banker.

Western Australia and South Australia have continued to deliver green or sustainable notes in large size, alongside the three biggest state issuers – New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland – which all have elevated funding requirements.

Supranationals and overseas agency issuers have stepped up their ESG Kangaroo programmes as the Australian dollar bond market's greater size adds to its longstanding diversification benefits.

ASFI taxonomy

The only corporate issuers this year have been five utilities, either domestic or from New Zealand, which have raised A$2.4bn.

The corporate patch was far broader in 2021 when telecoms firm Optus, retailers Wesfarmers and Woolworths and REITs – APPF, GPT Funds and Lendlease – sold sustainability-linked or green bonds.

One potential boost for corporate ESG supply, according to the sustainable finance banker, is the recently released Australian Sustainable Finance Institute’s taxonomy for green and transition finance, which improves transparency and robustness of labelled bonds.

Banks were also active in 2021 with Commonwealth Bank of Australia selling a A$500m 5.25-year green FRN in September, a month after OCBC Sydney’s A$500m three-year print.

Domestic sales subsequently dried up, though the majors can still access the receptive euro market as CBA and National Australia Bank did with green Tier 2 and senior trades last year.

Not only is there less pressure on banks to issue ESG bonds, reputational risk from facilitating coal-related transactions has diminished, particularly for issuers like PON with solid transition stories.

That contrasts with the noise that surrounded PON’s Yankee trade as well the media’s greenwashing accusations on the banks that facilitated PON’s sustainability-linked loans.

Since then, fanned by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, energy replacement has been superseded by energy security while the broader role of the "S" in ESG has been diluted, Scott said.

Political winds

Political momentum has certainly shifted away from ESG, both abroad, most obviously with the return to power of US president Donald Trump, and at home, providing cover for issuers, banks and investors.

The Australian federal election in May was devastating for the climate change sceptical Liberal/National opposition, but was also bad news for the Green party, which lost three of its four lower house seats.

The reelected Labor government has also proved less green than many had hoped or expected.

In December it controversially approved the expansion of four huge coal mines in New South Wales and Queensland before backing a 40-year extension to Woodside’s North-West Shelf gas project in Western Australia.