Origin story: how the IFR/Save the Children partnership began

The IFR charity tombstone auction to raise funds for Save the Children came as a surprise when it first started. Well, kind of.

When more than a thousand bankers gathered at the Grosvenor House Hotel on a cold, wintry evening in January 1997, most had no idea they were about to witness the start of something special. It was only the second time that IFR had hosted a dinner for winners of its annual awards. On the programme was an awards ceremony and – after success the previous year – a raffle in aid of Save the Children.

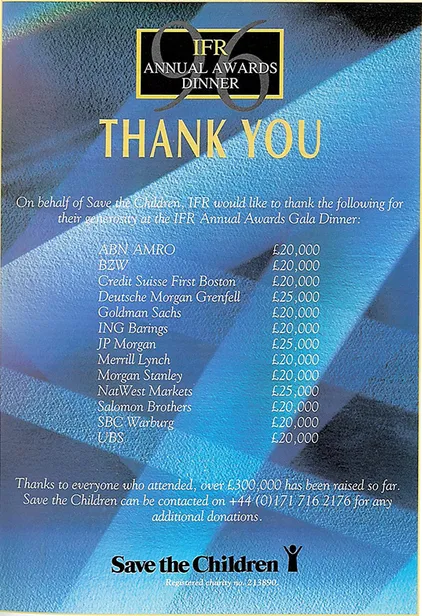

In the middle of the raffle, one guest rose to his feet and said: “BZW will pledge £20,000 to Save the Children.” Then a guest at another table stood up and raised the bar, pledging £25,000 from their institution. The impromptu bidding match eventually drew more than a dozen top-tier firms, raising more than £300,000 for the charity – a record for a single Save the Children fundraising event.

The interruption to the evening’s programme was presented as something wholly unexpected. But the spectacle was anything but. Keen to keep the event fresh and introduce a new twist following the success of the first awards dinner, IFR editor Simon Hylson-Smith had held a private dinner a few weeks earlier where the idea for an impromptu bidding match – all for charity – had been born.

“I organised a dinner for every head of corporate communications at all the major banks,” recalls Hylson-Smith. “I took them for a nice dinner on the South Bank, on the river, and then at the end said: ‘I've got one thing to ask you. We're going to do this award event, but we need some way of raising money'. And the head of corporate communications at Nikko came up with the idea.”

After the success of the supposedly “impromptu” scramble between banks to outbid each other, IFR introduced a “virtual tombstone” at the 1998 dinner, where banks were asked to bid for management roles in a phantom sterling-denominated bond deal for Save the Children. HRH The Princess Royal, patron of the charity, attended the dinner in a show of gratitude for the large sum raised the previous year.

As an incentive for banks to bid, Hylson-Smith persuaded the Financial Times to cover the event, giving publicity to the bidders. “We struck an agreement that they would run that virtual tombstone in a physical tombstone a day or two later,” he said. “So the people that were bidding had an opportunity to sort of get something out of it as well.” The first tombstone raised almost £600,000.

Unique partnership

Thus began a partnership that will celebrate its 30th anniversary in 2026. Over that period, the money donated by the banking and financing industry via IFR has totalled more than £33m, which has directly helped millions of people around the world, often those suffering acute hardship because of natural disasters, war and disease – or because of ongoing difficulties in accessing even the most basic of human needs.

“It's probably one of the most unique charity partnerships because of its longevity,” said Gareth Owen, who spent 17 years as humanitarian director at Save the Children. “I cannot think of a partnership that has lasted as long or has had as much sustained impact. It's very unusual to be able to count a partnership in the decades, so there's something very magical about that.”

One of the first places to benefit from the partnership was Rwanda, where Save the Children was helping victims of the 1994 genocide, which saw more than half a million of the country’s ethnic Tutsi population murdered and hundreds of thousands of women raped and abused. Money raised via IFR went towards improving health, nutrition, education and children’s rights.

The charity worked on various programmes in the country – including one to alleviate chronic malnutrition, and another to improve literacy for children under 10. It reached half a million children in its efforts to protect them from abuse, exploitation and child labour. It also helped trace parents or relatives of thousands of children who had become separated from their families.

By the late 1990s, with war once again rearing its ugly head in Europe – this time in Kosovo – funds raised via IFR played a critical role in addressing the resulting humanitarian crisis. With eight in 10 buildings destroyed, Save the Children distributed 18,000 kits of essential items, provided clothes to 115,000 children and helped 500 families set up at least one warm room in their house.

Save the Children also established a satellite telephone service to help families reconnect after having been torn apart by the conflict. It ran for four months until public telephone services resumed operation. In total, more than 84,000 calls were made, including 2,400 by children. As the country rebuilt, Save the Children stayed to develop a child immunisation programme and increase protection for vulnerable children.

“Organisations that have these kinds of partners have a tremendous amount of independence as a result,” said Owen, who was on the ground in Kosovo. “And that's a very, very important factor. It's beyond the money; the money helps us to maintain our independence as a charity, which is vital, especially in humanitarian work where there's geopolitics and everything else involved.”

Greater leverage

The flexibility of the funds raised via IFR makes them particularly critical for Save the Children. The charity raises about £50m a year in “unrestricted funds” – money raised from individual and corporate donors that comes with no strings attached and can be put to work speedily wherever it is needed. Money raised via IFR goes straight into the pot of unrestricted funds.

Save the Children uses this “seed capital” to pitch for additional funds from other donors such as the UK government, the Disasters Emergency Committee, the United Nations and World Bank – as well as from its other corporate partners. Such efforts have unlocked an additional £190m of “restricted funds” for specific projects, which would likely not have been possible without the seed funding.

“Every pound we get from IFR, we make it work hard by raising more money from other sources,” said Owen. “But the challenge with the other sources is they come with a lot of restrictions and are very location specific. By having a partnership that puts money into our general funds, we can leverage other sources and have greater impact. That is the vital nature of this kind of support.”

Flexible funding also means Save the Children can act fast. When Typhoon Haiyan, one of the most powerful on record, made landfall in the Philippines in November 2013, the charity sprang into action almost immediately – with IFR funds playing a major role. It brought in medical and sanitation equipment, shelter kits and blankets, mobile clinics and vital supplies that helped 800,000 people.

It was a similar story when the Ebola virus hit West Africa a few months later. Thanks to funding raised via IFR, Save the Children was able to open a treatment centre in Sierra Leona with 80 beds. Funds were also used to support children who couldn’t attend school and to help pregnant women give birth at home to avoid the danger of picking up the virus in hospitals and health clinics.

In 2018, funds raised via IFR were critical in helping Save the Children to respond to a catastrophic earthquake and tsunami that hit Sulawesi in Indonesia, killing more than 1,200 people. It responded immediately by providing emergency supplies and hygiene kits to families affected. It also set up child-friendly spaces in shelters for those who had lost their homes, to ensure families and children were safe.

Global citizens

With many charities struggling to raise funds given the economic strains on individuals and companies post-pandemic, and with many governments reducing their aid budgets because of fiscal constraints or because of a slow drift away from internationalism, partnerships such as the IFR/Save the Children relationship will increasingly play a major role in ensuring that those most in need get the help they require.

“A partnership like this represents a connection with the wider world, which is absolutely vital – more than ever if we think about how internationalism is being challenged in today's world,” said Owen. “Ultimately, that human connection, that hope is about international solidarity; it's about caring and concern for the distant other at times of need. That international solidarity is vital in today's world.”

To see the digital version of this report, please click here.

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email leonie.welss@lseg.com