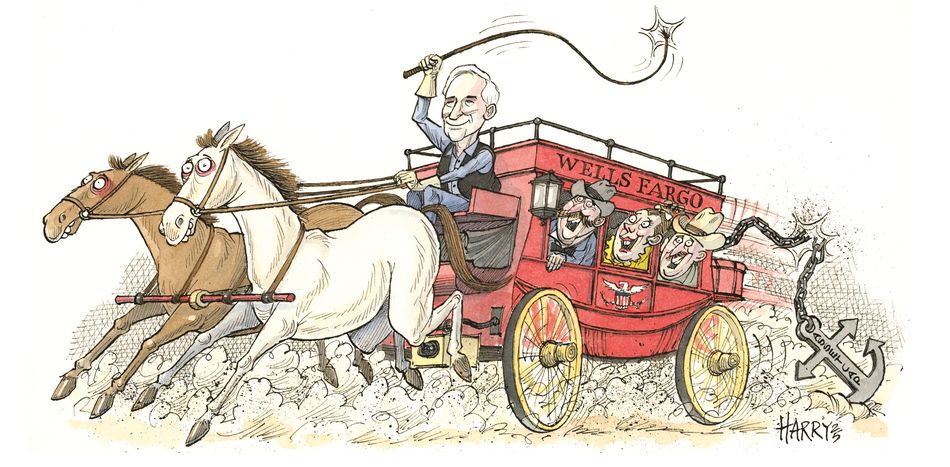

Bank of the Year: Wells Fargo

Unchained melody

After seven years in regulatory purgatory, Wells Fargo has not only shed its asset cap but reemerged as a leaner, more disciplined and more efficient competitor. For its methodical transformation and the unleashing of its corporate and investment bank, Wells Fargo is IFR’s Bank of the Year.

For seven years, Wells Fargo fought with one arm tied behind its back. But on June 3 2025, the US Federal Reserve finally delivered the news the bank had been waiting for: the US$1.95trn asset cap was history.

The removal of the cap – the most severe regulatory punishment in modern US banking – was a reward for a gruelling, multi-year overhaul of the bank's risk management framework, led by CEO Charlie Scharf.

2025 was the culmination of that effort – when the sleeping giant of American banking fully awakened.

For proof look no further than the US$59bn bridge loan for Netflix to help fund its takeover offer for (most of) Warner Bros Discovery. Wells Fargo is underwriting half the loan, with the rest split between BNP Paribas and HSBC, in what is the largest ever acquisition financing commitment by any single bank.

Could that have happened before the asset cap was removed? Almost certainly not. It would have simply consumed too much capital.

It is of course possible that the Netflix bid fails and WBD ends up being owned by someone else. But the fact that Wells Fargo was there with the money and – just as importantly – was trusted to provide Netflix with the M&A advice perfectly encapsulates the bank’s bounce back.

Taking over

To understand the magnitude of 2025 for Wells Fargo, it’s necessary to look back at the chaos of 2019. When Scharf took the helm, he didn't just inherit a bank; he took charge of a crime scene of broken trust and decentralised risk.

The asset cap was imposed on February 2 2018 – it was one of Janet Yellen's last official acts on her last day as Fed chair – because of what the Fed called “widespread consumer abuses and compliance breakdowns”.

From at least 2002 to 2016, thousands of Wells Fargo employees, driven by aggressive sales goals and high-pressure tactics, opened millions of unauthorised or fraudulent deposit and credit card accounts in customers' names without their knowledge or consent. The bank had also charged hundreds of thousands of customers for auto insurance they did not need and improperly applied fees to mortgage customers.

Scharf’s mandate was clear: "fix the bank”. And his strategy was surgical and brutal.

Between 2019 and 2021, he replaced most of the bank's top leadership and the bank moved from a federated model – in which risk was managed loosely by individual units – to a centralised "risk and control" organisation. The message was unambiguous: the old way of doing business was over.

Confirmation that Wells Fargo was no longer on banking’s naughty step was huge. “It was a pivotal moment in our transformation. It reflected the hard work of thousands of people over a multi-year period,” said Scharf.

But while Scharf doesn’t play down the significance of that moment, he is keen to look ahead.

“It was a milestone, not an end in itself,” said Scharf. “For the past six years, building our risk and control infrastructure has been our top priority. I've been very vocal about that. I've also been vocal about the fact that we were not standing still on the business. What the lifting of the asset cap meant was that we could move forward more aggressively to serve our clients and customers – and we were ready to do so.”

Fernando Rivas, Wells Fargo’s CEO of corporate and investment banking, underlines the point. “It was a really important achievement and milestone for the company. So we took the time to celebrate it and to recognise everybody who contributed to it.

“But very quickly it was in the past. And as Charlie says, we didn't come to the company to end the asset cap, we came to the company to build one of the greatest financial services companies in the world.”

More with less

And yet this is not just a tale of a Wells Fargo set to take off now the shackles have been removed. It’s also about the remarkable progress it has made over the past few years, even when being forced to do more with less.

When it comes to CIB specifically, Scharf realised that the unit could be a jewel in the crown and set about letting it shine. He carved it out as a separate reporting line when previously it had reported along with commercial banking.

“Charlie set up the corporate and investment bank as a separate entity and made it very clear that this is a business that we love and that we're going to grow and we're going to invest in,” said Rivas.

Given that investment banking is a fee business this was an obvious step for a bank forced to use scarce capital as efficiently as possible.

“It was a very clear part of the strategy to grow the fee-based businesses. There's a virtue in that necessity. I wouldn't choose that necessity, right? I'd rather be unconstrained than constrained. But clearly constraints force a certain discipline,” said Rivas.

Rivas joined Wells Fargo in May 2024 from JP Morgan and was keen to make the point that credit for the turnaround at Wells Fargo in general, and CIB in particular, should go to Steve Black as well as Scharf. Black became Wells Fargo chairman in 2021, joining from JP Morgan where he was vice-chair. (In October he became lead independent director when Scharf added the chairman title to the CEO role.)

Scharf and Black had worked together (with Jamie Dimon) to build leading investment banks at Salomon Smith Barney/Citigroup and JP Morgan. “This is Steve and Charlie's third time building a leading corporate and investment bank,” Rivas said.

But to make the turnaround work, Wells Fargo needed the right people.

“70% of any investment banking business is talent. It's talent, talent, talent,” said Rivas. “Tell me who your team is, and I might not tell you who's going to win the game but I'll give you a pretty good sense as to what your record is going to be at the end of the season.”

But why does the talent come?

“The talent comes because they see this massive franchise and all of these advantages that you can have as a banker on this platform. We have a very clear message – but it's not just the message, it's the credibility of the messenger. People need to look at the CEO, and they need to look at the leadership, and say, ‘they've been there, they've done that before, they know what they're doing, they know what it takes'.”

The other reason people were willing to leave established careers at other banks is that it’s more fun building a business than defending an entrenched lead.

That’s certainly the feeling of Jeffrey Hogan, the bank’s head of M&A who joined in May 2023 from Morgan Stanley. “I got excited about building something and spending the rest of my career in build mode rather than playing defence,” he said. “It’s not a bad thing to be one of the top firms playing defence, but it's really exciting to be at a firm that is playing offence and gaining share and growing its business.”

That perhaps explains Wells Fargo’s ability to bring in bankers at the top of their game from across the Street. The bank has hired more than 90 managing directors in the banking team in the past three years, another 30 in the markets operation and promoted another 270 or so to MD. The CIB leadership are all new to their roles since 2019, with 60% also new to Wells Fargo, including the heads of CIB, banking, markets and commercial real estate.

Making progress

So that’s the touchy-feely stuff, what about the numbers?

Rivas, considering the CIB specifically, points to one financial measure of progress: “If you look at the growth in the investment bank over the last several years, we took the business from US$14bn–$15bn in revenue to US$19bn. So we added US$4bn while we had an asset cap.”

Scharf, looking at the bank as a whole, prefers another metric. Crucially, it’s one he says captures profitability as well as growth. “Our returns on tangible common equity have increased from 8% to 14%–15% and we are well positioned to continue to improve both our returns and growth,” he said.

Investment banking fee league tables tell the story of how that came about. Let’s take the baseline as 2021 – the year that Scharf’s fightback took off. In that year, Wells Fargo’s share of US investment banking fees (capturing M&A, bonds, equity and loans) was 3.13%, according to LSEG data. In the 2025 IFR Awards period, from January 1 to November 7, it was 4.53% – an increase of 140bp. That’s way better than any other big US bank. In terms of league table position, the bank jumped to sixth place from eighth.

In global terms, the improvement is similarly dramatic – from 11th in 2021 to seventh four years later with wallet shares of 1.68% and 2.47%, respectively – even though, let’s be honest, Wells Fargo is still a largely US operation, albeit one that has a growing presence in Europe and Asia.

But that picture is too broad. To get a real sense of the progress made it is better to look at individual products and asset classes. On LSEG's numbers, the US DCM operation saw Wells Fargo's wallet share rise from 6.10% to 6.57% (up 47bp); US ECM from 1.82% to 2.68% (up 86bp); US loans from 5.63% to 7.37% (up 174bp); and completed US M&A from 0.95% to 1.55% (up 60bp). For announced M&A and using volume credit rather than fees, Wells Fargo's market share is 8.24% for the 2025 awards period, up from 2.68% in full-year 2021 – an increase of 556bp, and that was before the Netflix-WBD gig.

M&A momentum

There isn’t space in this article to go into every asset class in detail, so let’s look at the progress Wells Fargo made in a selection of businesses and allow that to stand in for its achievements elsewhere. Let’s start with M&A.

According to Tim O’Hara, head of banking, the Wells Fargo he joined in May 2022 from BlackRock had a number of leading franchises – the commercial real estate business is one of the great franchises in banking, for instance – but there were areas that needed filling out. “We had some great franchises in a number of places, and some great people in them; I'd put them up against anybody. But a lot of what we've been doing over the last three years is investing in some of those areas where we [weren’t as strong],” he said.

The point is underlined by Hogan. “In M&A we've made a huge investment, not only in talent, but also in everything that we do in order to advise clients on the most complex, the most interesting transactions that we can,” he said. “I think 2025 is the year that our practice hit escape velocity. It is the year that we have really redefined how our clients think about Wells Fargo M&A.”

The highlights include being sole or lead adviser on QuikRete’s US$11.5bn purchase of Summit Materials; on Berry’s US$17.6bn merger with Amcor; Union Pacific’s US$85bn takeover of Norfolk Southern, and on the US$34.5bn merger of Cox with Charter Communications. Wells Fargo was also financial adviser to controlling shareholder Rank Group on the US$6.7bn sale of Pactiv Evergreen.

The QuikRete deal involved Wells Fargo underwriting a US$10.7bn non-investment-grade financing, which at the time was the largest sole underwrite for non-IG debt.

“I think it's fair to say that the Wells Fargo of five years ago would not have sole underwritten a US$10.7bn commitment,” Hogan said. “I think we would have been too gun-shy about our ability to successfully distribute that risk. We’re now much more comfortable taking on that kind of risk and taking it on in size.”

Changing roles

Talking of punchy underwrites brings us to the syndicated lending and leveraged finance teams, where progress is measured not just in league table credit and wallet share (though both have grown significantly), but also in the kind of deals Wells Fargo did.

“Both the leveraged finance and the IG businesses have been core capital markets businesses for Wells Fargo for many years, but what you’re seeing now is the growth in strategic financings,” said John Hines, global head of investment-grade capital markets.

The bank’s roles also changed for the better (and more lucrative). “One of our areas of focus this year has been migrating to the left [on deals],” said Alexandra Barth, co-head of leveraged finance.

Highlights included acting as lead-left on the QuikRete transaction and lead-left and/or joint lead for the financings that enabled the acquisition of SpartanNash (US$400m TLB), Spirent Communications (US$600m TLB), H&E Equipment Services (US$750m TLB and US$2.75bn senior notes), IGT/Everi (US$2.475bn TLB and US$1.85bn senior notes) and Pactiv Evergreen (US$2.91bn TLB/DDTLB and US$1.415bn senior notes).

A change of roles was also a feature of Wells Fargo's year when it came to ECM. After years playing a secondary role, the bank made a decisive push to reclaim relevance by hiring Jill Ford and Clay Hale in late 2023 as co-heads of ECM while Craig McCracken was retained to oversee equity-linked capital markets, building on a historic strength.

Notable lead-left or active bookrunner slots came on deals for Euronet (US$1bn CB), Firefly Aerospace (US$999m IPO), American Water (US$1.15bn follow-on) and Cloudflare (US$2bn CB).

Arguably, there was no bigger power play in US ECM than QXO and its all-primary stock sale in June. It was a deal that everyone knew was coming, and Wells Fargo made sure it was involved.

The result was a US$2bn overnight ABB on which Wells Fargo slotted in alongside incumbents Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley.

Similarly, in a transaction that had been years in the making, Wells Fargo was a bookrunner on the US$931.5m IPO of SmartStop Self Storage REIT that priced on April 1.

“SmartStop is a good example where we can really bring the entire bank to bear,” said Ford. “From our private bank to our commercial bank, we got to know this company deeply over the span of 10 years.

“We were in a position to not just lend capital but really advise on how to position the company for the public equity markets.”

Other areas of the capital markets where Wells Fargo has made admirable progress include structured finance. The bank is IFR’s North America ABS House for 2025 but has also made an impressive impact in the MBS markets – and CMBS in particular – building on its market-leading commercial real estate business across structured finance, lending, advisory, DCM and ECM.

Wells Fargo similarly made a splash in the investment-grade and high-yield bond markets – with too many deals to mention.

The upshot of increasing seniority of roles? The bank says its average transaction size is now US$1.5bn, up 39% from 2021, while lead-left term loan B and high-yield bond mandates are up 81% by value and ECM fees are up 15% from lead-left or active bookrunner roles.

Markets magic

Even if there was – if you look hard enough – a virtue in the necessity of the asset cap when it came to investment banking, that was much harder to spot for the markets business.

The cap inevitably became a handbrake on the bank’s ambitions in global markets, a set of activities that typically operates with higher leverage than other parts of the bank.

For that reason, Wells Fargo’s progress in sales and trading over the past few years is even more impressive. Trading revenues jumped 44% between 2022 and 2024, comfortably outstripping the industry average of 3%. That growth has slowed over the first three quarters of 2025, but the bank is still on track for its highest revenue haul since it began breaking out trading numbers as it continues to invest in the business.

“Wells Fargo, over the years, has assembled a lot of the pieces that it needs to have a successful markets division,” said Dan Thomas, Wells Fargo’s co-head of markets with Mike Riley.

Capping the level of assets that a bank can hold limits how much balance sheet it can deploy to support its markets activities, whether that’s equity prime brokerage, secondary credit trading or being a primary dealer for US government bonds. Wells Fargo was nonetheless determined not to jettison those services, knowing that they remained pivotal to securing business with its core clients.

Instead, the bank had to figure out how “to operate things on a sub-scale basis”, said Thomas. “The firm had a lot of patience because it didn't want to make bad strategic decisions [and exit businesses] just because of the asset cap.”

As well as enforcing discipline around balance sheet resources, Riley said a positive aspect of the asset cap was that it brought the management team together to work much more closely across markets. “People had to make decisions that didn't make sense on an individual business basis, but made sense for markets, or CIB, or the bank as a whole,” he said.

As a result, Wells Fargo was in prime position to make the most of the surge in client activity that characterised the post-pandemic years.

That included building its FX and rates trading franchises, resulting in doubling its FX client base between 2021 and 2024 and a significant jump in revenues.

Wells Fargo also reaped the rewards of technology investments as electronification intensified across asset classes. “We invested in technology pretty much in every business,” said Riley. “We started investing in that later than a lot of our peers so we could invest the right way, as opposed to trying to integrate a bunch of different attempts at building electronic trading.”

Big fan

For an unbiased view on Bank of the Year candidates, IFR sometimes turns to Mike Mayo, the doyen of banking analysts. But that wasn’t possible this year: he works for Wells Fargo. Instead, we canvassed Ebrahim Poonawala, a bank analyst at Bank of America.

He’s a fan of Wells Fargo – and Scharf in particular. “The key man is Charlie Scharf. He has vision, he gets it. So far, he’s proven himself to be a very strong operator,” said Poonawala.

On the removal of the asset cap, he said: “[It’s] huge for Wells’ ambition, in terms of their ability to provide financing in capital markets … I don’t think they would have been on the Netflix/Warner Bros financing if the asset cap were still on.”

That last point is surely true. But ask Scharf whether Wells Fargo’s advisory role on the potential Netflix/WBD deal – and its willingness to back the deal with a record underwrite – was a pivotal moment and he refuses to bite. “Going from number 14 in 2021 in the US M&A league tables to number seven today is a better testament to our progress than any single transaction. It shows very broadly that Wells Fargo's financial and intellectual resources are a significant competitive advantage for us in investment banking. We're going to keep building on these advantages.”

Asked how he sees the transformation of CIB since he took over as CEO, and Scharf again insists on a forward spin. “The corporate and investment banking transformation is one of the most significant accomplishments of the past five years, but it still remains one of the great opportunities in front of us,” he said.

“What we're doing today is using our competitive advantages – including decades-long deep relationships with large corporates and middle-market companies, a complete product set, significant existing credit exposure, strong risk discipline, and the capacity and resilience to support our clients and invest through cycles – to grow the business further. We have driven growth through investments and talent, and we'll continue to.”

Additional reporting by Christopher Whittall, Philip Scipio, Michelle Sierra and Stephen Lacey