UBS’s new-look trading division flourishes in 2025’s volatile markets

UBS’s emergency takeover of Credit Suisse in 2023 was a transformational moment for the Swiss lender, cementing its place as a wealth management behemoth.

It looked to be a more low-key event for UBS’s trading division, which became an industry byword for conservative capital management over the previous decade following a dramatic restructuring in 2012. Consensus held there was just too much overlap between the two Swiss giants to move the dial in global markets.

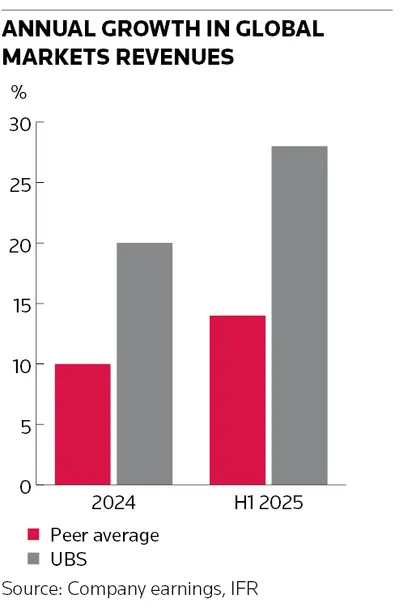

Fast forward to the present day and UBS has registered the quickest growth in trading revenues among the largest global investment banks over the past 18 months, comfortably outpacing bigger rivals like JP Morgan, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley.

UBS’s capital-light trading model remains intact. But the Credit Suisse acquisition has nonetheless allowed it to flesh out businesses and regions where it lagged competitors, while helping it reinforce mainstay activities like equities and foreign exchange trading.

“The strategy remains the same, but the Credit Suisse acquisition has really turbocharged our growth while making us better, broader and more diversified,” said Jason Barron, head of global markets at UBS. “It’s helped us gain share in champion businesses like equities, financing and FX, and allowed us to accelerate in areas where we were underweight, like the US and in fixed income trading.”

There’s no doubt that 2025’s volatile market backdrop has played to UBS’s strengths. US president Donald Trump’s erratic trade policies forced investors to rethink their exposure to the US dollar and ignited a flurry of stock-trading activity, delivering a bumper payday for equities and currency traders.

UBS posted a record US$4.8bn of markets revenues in the first half of the year after growing at roughly twice the pace of its main rivals, buoyed by record results in equities and a significant bump in FX trading.

“[Tariffs were] a surprise for the market that forced clients to hedge or reposition their books,” said Paolo Croce, head of global markets for EMEA at UBS. “Volatility increased together with clients’ activity, creating a more conducive environment for the market business overall.”

Material gains

UBS’s 2024 earnings show the upturn wasn't a flash in the pan. The bank reported a 20% annual rise in markets revenues last year, roughly double the industry average, with a record US$7.5bn haul as the Credit Suisse acquisition started providing a meaningful tailwind.

“We were adamant from the start that markets wouldn't take CS systems and infrastructure because otherwise you're not servicing clients properly through that period,” said Barron. “This integration was very much about people, clients and positions, which is really as it should be.”

UBS has increased headcount in global markets by 15% since the integration. It also retained an even higher proportion of senior Credit Suisse investment bankers to increase its presence in dealmaking. Many of those were in North America where Credit Suisse’s 1988 takeover of First Boston had given it a formidable outpost.

The boost to UBS’s stalwart equities and FX businesses was almost instantaneous. As well as enjoying a material uptick in FX trading volumes, UBS said it broke into the top three banks in cash equities trading in late 2024 after bringing on board Credit Suisse programmers to upgrade its algorithmic trading technology, which complemented a push on “high-touch” trades involving human salespeople.

Elsewhere, notable Credit Suisse additions included roughly US$13bn of equity derivative positions and US$18bn of assets from quantitative investment strategies – a fast-growing business where banks sell off-the-shelf products replicating complex hedge fund trading strategies.

“We assumed a lot of the [Credit Suisse] business had tailed off as clients departed after they shut down prime brokerage. What we actually found when we reached out to clients was a huge amount of goodwill and lots of them actually wanted to come back,” said Barron.

Fixed income heft

Cherry-picking parts of Credit Suisse's operations upped UBS’s presence across other regions such as the Middle East. Perhaps the most notable shift, though, came in the business that bore the brunt of UBS’s 2012 overhaul: fixed income. That retreat from trading bonds and derivatives linked to interest rates and corporate credit released vast sums of capital.

There was, however, a notable downside: UBS's markets division became increasingly lopsided. Fixed income accounted for around 30% of UBS’s total trading revenues in recent years, about half the industry average.

“We identified in 2021 that we were underweight in certain areas of fixed income that aligned with our strategy, and we needed to diversify our revenue streams, but it was nearly impossible to grow organically because of the war for talent," said Barron.

The Credit Suisse takeover allowed UBS to add heft almost overnight. The bank carved out Credit Suisse’s highly regarded US loan trading team – and part of its loan book – to turbocharge a broader rebuild of UBS's global credit trading franchise.

Importing a significant chunk of Credit Suisse’s fixed income solutions business provided further ballast to that effort, helping UBS become one of the top issuers on the multi-dealer SPIRE structured notes platform.

“Our risk appetite hasn’t changed, but we did already have risk appetite for more than we were doing before the Credit Suisse integration,” said Barron.

“Once we looked under the hood, it became clear that CS derived a lot of their success in very different ways to us ... [and] they had very high-ranking businesses in areas we were still looking to grow."

Pragmatic approach

UBS hasn’t strayed from its long-held obsession with financial resources. The investment bank’s risk-weighted assets remain capped at 25% of the wider UBS Group’s total RWAs – a ratio that stood at 22% in the second quarter. Contrast that with Barclays – which is on a mission to slash RWAs – where the investment bank accounts for 56% of RWAs.

"We don’t have unlimited resources, so we have to pick the areas where we can be relevant for our clients," said Croce. "If we want to remain a top player in areas like cash equities, FX and equity derivatives, then there’s a certain amount of capital resources that need to be allocated to these businesses."

There is certainly a pragmatism in UBS’s approach that many competitors are still reluctant to advocate publicly – even if they practise it privately. Take its view on nonbank trading firms, which have grown in prominence as the likes of Citadel Securities and Jane Street have expanded rapidly in recent years.

Barron said UBS has been “leaning in quite heavily” to some of these trading firms since about 2015 and has invested significantly in controls and infrastructure to work with them.

“Our view is this has been inevitable since the [2008] financial crisis because of the changes to how banks are regulated from a trading and capital point of view,” he said. "We don’t see them as competitors; we very much see them as partners.”

This willingness to look for outside help is not just confined to markets where UBS has a smaller presence. Barron said part of UBS’s success in cash equities has come from partnering with these firms. “Our business model is about liquidity provision to all our clients and these trading firms are part of that liquidity stack,” he said.

Looking ahead, UBS still sees room for growth in its markets business. Barron expects FX trading to remain busy as clients reassess their exposure to the US dollar – a “huge change” in behaviour. He also sees more gains coming from the bank’s extended footprint in dealmaking and research, particularly in the US.

“There are still huge amounts of upside,” he said. "Banking is an important part of markets: primary business helps to attract secondary business.”